How CityLink helped ease Melbourne’s traffic gridlock nightmare

If you think the Monash can feel like a car park now, spare a thought for drivers who had to tackle Melbourne’s traffic snarls before the CityLink toll road opened.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Melbourne has gone through a significant transformation in the past 30 years and little has impacted city life more than CityLink.

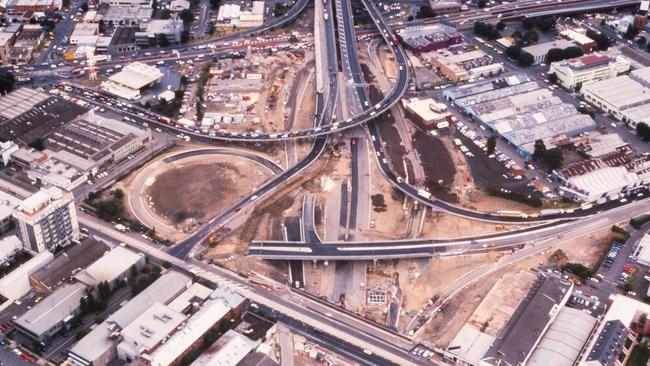

After three years of construction, the ground-breaking project opened to motorists in 1999 — linking Melbourne’s major freeways for the first time and cutting down the crippling traffic that plagued the city.

Before CityLink, all traffic was forced to travel through the city to go from north to south or east to west, creating a gridlock that is hard to imagine more than two decades on.

Darryn Paterson, general manager of strategy and traffic at Transurban — the Melbourne-born and based company behind the project — said the task of planning how to connect the busy Tullamarine, West Gate and Monash freeways in what was already a bustling city was one of its greatest challenges.

“It’s hard to conceive now. You had all of this traffic that poured out into streets and everyone had to fight their way through to find a connection,” Mr Paterson said.

“Most people weren’t destined for the city, they were trying to get to somewhere else, but they had no choice.

“Trying to work a way around that, in what was already an established city, would have been incredibly complex.”

One of the biggest road projects on a state and national level at the time, engineers turned to innovative techniques to make CityLink a reality.

On the Western Link, 3500 precast concrete road segments — weighing up to 80 tonnes each — were linked together in what was a first for Australia.

Now, precast is widely used in infrastructure projects.

“People don’t even think about it now, it’s a standard approach, but at the time not many places in the world had done this,” Mr Paterson said. “It’s quite remarkable.”

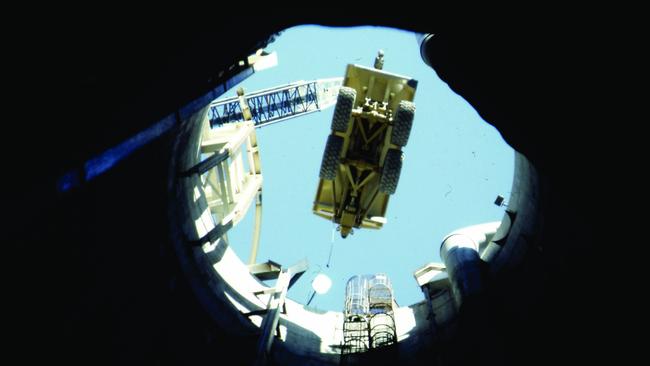

Although it was only one element of the sprawling CityLink network, the Burnley Tunnel was a feat of engineering in its own right when it opened in 2000.

Built beneath the Yarra River, engineers had to freeze the unstable ground to allow for safe excavation of the lengthy 3.4km tollway.

“The length of the tunnel is pretty much what the West Gate Bridge is — if you put it upside down and under a river, of course,” Mr Paterson said.

“The scale of the project was so large and the environment was so complex and challenging, when you compare it to something like the West Gate Bridge, you start to get a sense of what they were trying to achieve.”

On the Tullamarine Freeway, an island — made up of 200,000 tonnes of gravel — was created to allow for the Bolte Bridge to be built.

The island, in the middle of the Yarra River, provided the main support for the instantly recognisable bridge.

It was not engineering innovation that was key to the development of the project — cutting-edge technology on CityLink also provided a major turning point for Melbourne congestion.

One of the first roads in the world to use free-flowing electronic tolling instead of coin-collecting toll booths meant that traffic could always be moving.

“It was critical to making (CityLink) successful, but it was a major risk that they had taken on board,” Mr Paterson said.

“From everyone’s perspective, looking back on it I think it’s safe to say that was absolutely the right decision.

“People weren’t being put in the position where they had to stop and start, and it meant a lot more connections could be put in place.

“You can imagine if we had to put a toll booth between every single on and off ramp — it would have been counter-productive and not worthwhile doing.”

WHAT LIES AHEAD FOR MELBOURNE’S ROADS?

As Melbourne changes so will the city’s roads, with new technology looking set to transform how we travel.

While major projects — including the West Gate Tunnel — will upgrade and improve Melbourne’s transport network to cope with issues such as congestion, roads of the future will also be adapted to accommodate cutting-edge motoring technology.

Transurban predicts self-driving cars — also known as connected and automated vehicles (CAV) — will become a mainstream mode of transport in the next 15-20 years.

Henry Byrne, Transurban’s group executive of Victorian business and strategy, revealed the company had been running trials on the futuristic vehicles to learn how roads needed to change in order to adapt to the innovation.

“The trials are looking at how CAV technology interacts with current infrastructure and where design features may need to be reconsidered,” Mr Byrne said.

“For example, an autonomous vehicle might have difficulty recognising which sign to follow, particularly coming off a ramp, or road markings may need to change so CAVs can read them better.”

Although this travel may be a few years off, zero emissions vehicles are growing in popularity and accessibility.

In the next three years, the number of electric car models in Australia is expected to triple.

MORE NEWS:

VICTORIA TO HAVE LARGEST BATTERY IN SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE

INSIDE WERRIBEE ZOO’S $84M TRANSFORMATION

HOW WEEKEND TRAFFIC FUELLED $813M TOLL BONANZA

Sustainability will also play a role in the road design of the future, with tweaks being made to the engineering and construction to ensure new roads are as green as possible.

“As a company, we have our own targets for reducing our carbon footprint and when we think about customer emissions, it plays into things like gradients, materials we use, the construction process,” Mr Byrne said.

“It’s an incredibly important and growing focus to ensure we achieve these reductions that

we’re targeting.”