Hawthorn 1991 premiership player Paul Dear battling pancreatic cancer

“I’ve forest bathed … met shamans, Aboriginal healers, wizards.” With pancreatic cancer, Norm Smith medallist Paul Dear knows the odds are stiff, but he isn’t giving up the fight.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“I’ve sat in thermal springs in WA and NT which locals believe have healing properties. I’ve been prayed with in a cafe in Kununurra. I’ve walked bare footed on the local golf courses and ‘forest bathed’. I spend a lot of time walking by the beach, especially at sunset. I’ve seen more sunrises in the last 11 months than any other time in my life. I’ve embraced Wim Hoff breathing and I try to meditate. I’ve met shamans, aboriginal healers, wizards … this experience has opened my mind to other aspects of life. I’ve also got a new appreciation for nature and the simple pleasures in life … I had part of my pancreas removed, my spleen, my gall bladder, my appendix and part of my liver.”

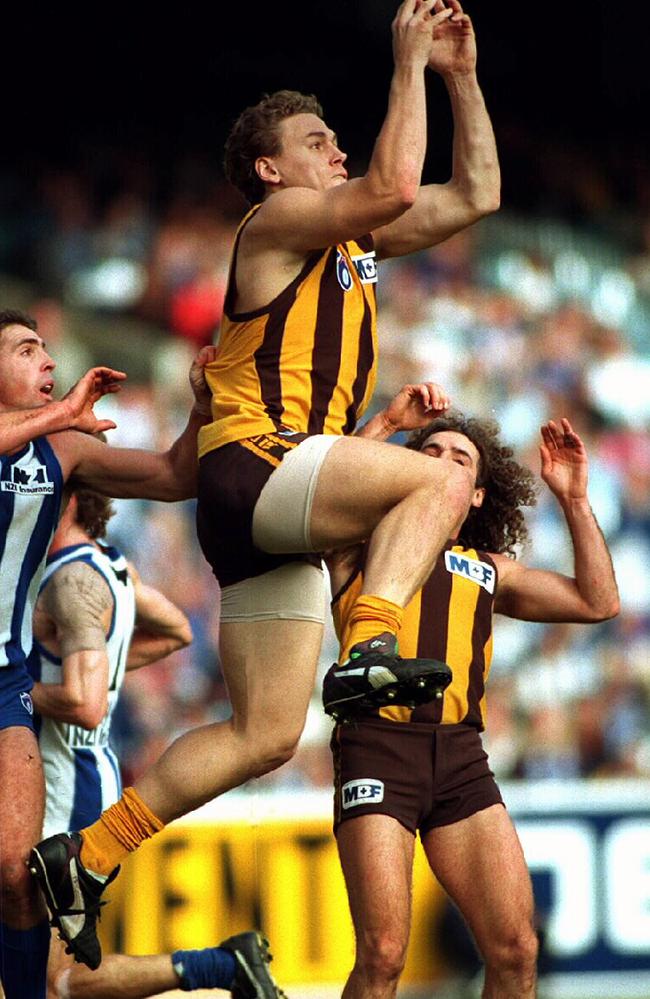

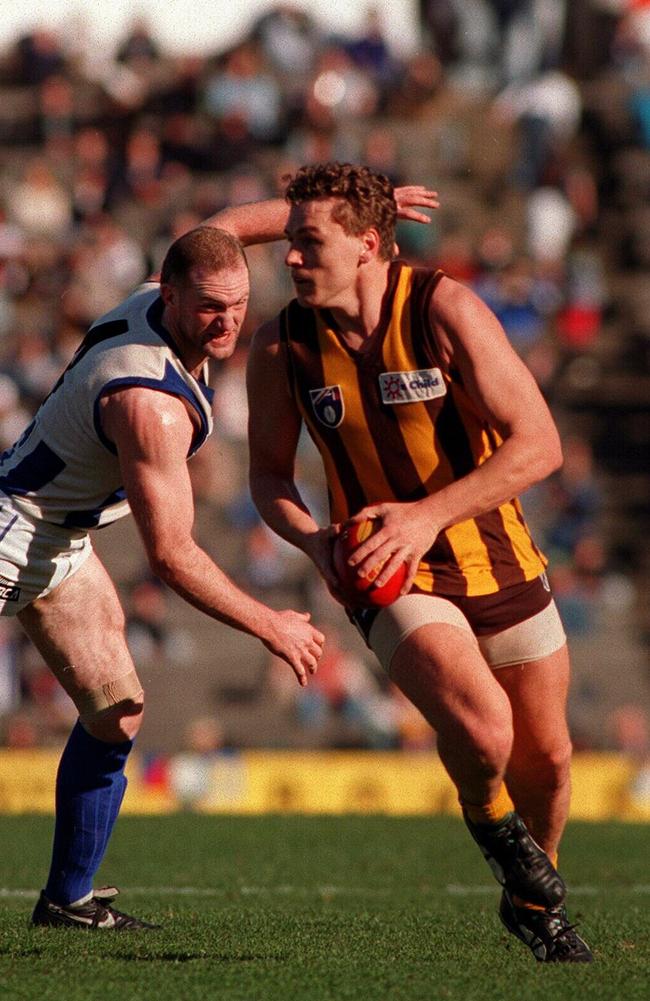

Paul Dear was a part of the Hawthorn side that won the Premiership in 1991. He always had to fight hard for his spot on the team, and when his time came on the biggest stage, he stood tall – winning the Norm Smith medal. Now, he faces his biggest battle yet after being diagnosed with stage four pancreatic cancer. He and his wife Cherie spoke about the cruel diagnosis, the practicalities of dealing with an uncertain future, telling their kids, and how they’ve chosen to spend their remaining time together.

HM: Paul, if you’re doing the Norm Smith voting in 91’ – who would you have given the votes to?

PD: Me!

HM: A premiership medallion, a Norm Smith medallion – you play the only Grand Final at Waverley Park, and Angry Anderson and the bat mobile come into your life. What a week.

PD: I loved Waverley. The openness worked well for me.

HM: That was September 1991. A huge month, a huge day, a life changer. Sadly, September 2020 was life changing too.

PD: It was. I’d had a bit of indigestion, a bit of a change in bowel movements. I decided I’d head down to the local doctor and get the full once over. Due to my family history, he decided that on top of the bloods I should get a CAT scan. We weren’t thinking it was anything major. I got a call the day after I got the scan — “The doctor wants to see you”. That didn’t sound good. The scan showed there were masses in my liver. It brought back some painful memories of my sister’s diagnosis.

HM: She died of bowel cancer in 2017.

PD: She had bowel cancer in her early 40s, and only lived for two years and eight months. If it was the same, I knew I was in a bit of trouble.

HM: At what point did your doc tell you that you’ve got Stage 4 cancer?

PD: Initially he told me that I had shadows in my liver, and he’d already arranged for me to see a colorectal surgeon the next day. I left assuming it was stage four as I knew it was unusual to just get a primary in the liver.

HM: This was all happening in lockdown. You weren’t even necessarily getting face-to-face appointments with specialists or being able to get into hospitals. It happened quickly.

PD: It was tricky. Before each procedure I had to have a Covid test and isolate. Cherie had to just drop me off and I went in alone. The initial thought was it was bowel cancer, simply because of Nicky’s diagnosis. I went and had a colonoscopy and a gastroscopy, and when I woke up from that, the surgeon said he’d found nothing. That wasn’t good news. I’d gone to Dr Google by then, and I knew the options I was left with weren’t good.

HM: From there?

PD: After that they organised a biopsy of the liver, that’s when the news came back that it was pancreatic cancer.

HM: At that point, you were told its Stage 4 pancreatic cancer. They say, there is no way we can operate, and there’s no real treatment.

PD: In terms of what’s known, and the statistics, there’s no cure. Their recommended treatment from that point is what they call palliative chemo. Having chemo to extend life. My options were: have chemo until either your body rejects it, or the chemo stops working.

HM: Did they give you a lifespan? An outlook?

PD: I asked the question – have I got 10 years? He said no. Five? Maybe. Two? Probably. “But if you don’t get treatment now, you won’t last ’til Christmas.”

Cherie D: Paul and I were both in that conversation and I heard “possibly”. They always say for big news like that you should have more than one set of ears there taking the information in. They know that patients in shock can only take in a minimal amount of information. Our girlfriend’s sister had just had the same diagnosis, and they thought she was going to be OK. She was given a return-to-work date, and she passed away the weekend we were waiting for Paul’s results. She only survived nine weeks.

‘It was a shock (to the kids) but they knew every moment was precious’

HM: After you two have walked out, how then do you tell your kids?

CD: It took a week to get that diagnosis, which is quick for pancreatic cancer. In that period, we didn’t want to say anything to the kids, until we knew what we were dealing with. We later found out the cheeky buggars had been stalking us on Find My Friends. They knew that we were going to doctors and hospitals. They are their own little team, and they were ringing the eldest, Harry, who was living in Sydney at the time. They were telling him something was going on. They’d heard me crying in the shower. We had to get the three of them together, and Harry on a phone call, and we sat them down and told them.

HM: How did they respond?

CD: We are fortunate that our kids are very much like Paul. They are all calm, and they don’t get overemotional about things. They’re pragmatic like that. There were tears, and we tried to deliver the news as honestly as we could. But we wanted to let them know that it’s not necessarily going to happen to dad. We can listen to what the doctors are saying, but we don’t have to take it as a given. Statistics are about groups of people, and Paul’s an individual. We said from the start that we wanted him to be an outlier, an anomaly, a statistic of one. We told the kids that as well. They are old enough to be brought along on that journey.

PD: They’d been through the journey with my sister because they were very close to her. They knew what it looked like. It was a shock but they also knew that every moment now was precious. Just make the most of it.

‘I’ve never worried about dying (but) … let’s not focus on the dying, let’s focus on living’

HM: Listening to you both talking – you have an extraordinarily positive attitude. I assume at some point you sat down and said, “How are we going to attack this?” The news is terrible, but in a similar vein to Neale Daniher, you at some point make a choice. Did you have that chat, or did it evolve naturally?

PD: I’ve always had a very simple philosophy in life. When your time’s up, your time’s up. I’ve never worried about dying. Everyone is going to die, it’s just a matter of when. Our reflection was very much along the lines of, let’s not focus on the dying, let’s focus on living.

CD: He’s a Shawshank Redemption man.

HM: Get busy living, or get busy dying.

PD: And several times along the way, we have said, this is a shit situation, but people are in much worse situations. There will be people leaving this earth before me. We’ve been given a chance, let’s make the most of it.

CD: Paul is my soulmate. We have always had a very happy marriage, and we’re very much a team. He is my anchor. I was completely devastated, and I woke up the morning after diagnosis and I was in that moment where I’d forgotten. But then you remember, and it all hits you again. I was sobbing. Then I had this realisation that if Paul only has a short time left here, I don’t want to spend that time crying and making him unhappy. What’s the point being miserable when you are still together and he’s still alive? I also made a conscious decision that I wasn’t going to burden him with my misery while he’s here. I focused on making this the best possible experience for all of us. I wanted to live with hope. Doctors make you feel hopeless, helpless, powerless. We were told that Paul may not be able to tolerate chemo, that it’s only a small percentage of patients who can have it. Then out of that, if you can have the chemo, will it be effective? Then, if you can have the chemo and it’s effective, will it be too toxic for you? I know of someone younger than Paul who had the same chemo, and with his first treatment, he ended up in an induced coma for three days. That’s how toxic it can be. Paul was lucky, he has been able to mostly tolerate the chemo, but not without side effects like neuropathy in his hands and feet.

PD: The first couple of months were hard because it’s just a complete shock to your body, and also there’s the emotional trauma of coming to grips with the news. If I didn’t have the support of Cherie behind me, it’s very easy to fall in line with what the doctors are telling you. You need to challenge them. With Cherie’s unbelievable research and networking capabilities, we started to pull together what we felt we needed to do.

‘We were walking around a cemetery, looking at where Paul might be buried’

HM: The pragmatic stuff – you update the wills. How confronting is picking out a spot in a cemetery?

CD: That was awful. In a way you must get comfortable with dying so you can get on with living. We made the decision to get the practicalities out of the way quickly. We didn’t want to wait until a time where Paul might be sick, so we had to have those conversations. We wanted to get that out of the way so it was done.

HM: Conversations you don’t often contemplate.

CD: Or choosing a burial site. I knew Paul wanted to be buried, but living in Melbourne, you don’t have a lot of options. It’s not like you can easily be buried down the road. We went down to our local cemetery one Friday night, and the one available plot was in a neglected part of the cemetery. It upset me so much. This was not a place where I could bring the kids to come and remember Paul.

HM: What a horrible process.

CD: Horrible. Then you are hit with that thought – how have our Friday nights come to this? Pre-Covid, every Friday night our three youngest kids played competitive basketball, so we were driving all over Melbourne to games. We used to think that was tricky! Now we’re walking around our local cemetery looking at where Paul might be buried.

PD: What we’ve learnt over the journey is things can change quickly. We’ve got that out of the way so if worse comes to worst, a lot of the planning has already been done. I know at least the family has a plan and a way forward.

HM: Have you been surprised by the support from friends and extended family that has come your way?

CD: Overwhelmed.

PD: Blown away by the support, especially through the local community. Cherie has been an active member in the community, been on the committees, team manager for kids, kinder president …

CD: I did a fundraiser when Nicky was diagnosed, and I worked for a children’s brain cancer charity. All those connections that I’d made in the community, and all that volunteer work, has come back to us tenfold. That’s been one of the beautiful parts of this whole story. What you put out will come back to you! We had friends set up a meal roster, so I always knew that the family had a healthy meal prepared. That took an enormous amount of pressure off me to know that there was a meal coming every night. For the first couple of months, I don’t think a day went by without some sort of drop off or delivery at the front door. It was so uplifting to know how many people cared about us.

HM: I assume the Covid aspect to this has put another layer of complexity into it. Even little things like instead of having your wife hold your hand while you are being treated, there is no one in the room with you.

CD: They told me I couldn’t go to that first appointment when the oncologist was going to confirm that it was stage four. Things like that made me really upset – I had to ring and beg. I’ve never been to chemo with Paul, but I think that suits him. He likes his iPad, his noise cancelling headphones – he likes the lack of fuss.

PD: When I’m sick I’m OK with the solitude, however Covid meant that the family couldn’t even drop off food. It also meant Cherie couldn’t come to a lot of the appointments and because of her research she was the one with all the questions.

‘We started looking at alternative treatments to cope with chemo’

HM: How far have you looked for mechanisms to cope with what you are going through? Alternatives?

PD: When I was diagnosed we immediately started looking at alternative treatments to help me cope with chemo and also we started to find out there were things others believed could actually address the cancer too. For example: After round eight of chemo I was in hospital throwing my guts up for five days, and they were injecting me with all sorts of things to try and stop me, nothing was really working.

CD: When this happened I had an appointment with a highly-regarded Professor of Integrative Medicine. I said “Paul is in hospital, he can’t stop vomiting, and he’s losing weight”. He said, “Have they tried chewing gum?” In all honesty, it made me a little angry. I’d paid a lot of money for a consultation for him to tell me that! On the way back to visit Paul I bought some chewing gum, and I went in and saw him. He tried the chewing gum, and lo and behold …

PD: The next day I was out of hospital.

HM: Wow – who would have thought.

PD: It made sense. I remember doing road trips with the family, and there were seven kids, mum, dad and sometimes two dogs in a Kombi. Going down the Great Ocean Road, my brother would throw up every five minutes. Thinking back to those days, they were about the only time we were allowed to have lollies. They’d be rationed out in the car.

CD: We don’t fully understand the theory but there have been studies done here at the Royal Melbourne where gum has been used to reduce nausea after surgery. It’s to do with the chewing. At this stage we were prepared to try anything especially given it was cheap and harmless. It’s become part of Paul’s treatment kit with chemo. When you take medication it generally creates side effects, then you take another medication to stop that side effect, then that creates another problem.

PD: We tried to minimise pharmaceutical intervention as much as we could and tried to find natural solutions. I’ve never wanted to take a Panadol for a headache or anything like that anyway. So now I carry chewing gum and when I feel nauseous, I chew on gum.

CD: There are so many alternatives out there and sometimes you can be warned off that they are just scammers who want your money but the reality is, I have been more overwhelmed with how many good people there are out there that are trying to help with no expectation of anything in return.

PD: There are costs associated with a lot of these treatments and the issue is they aren’t covered by Medicare or private health insurance which is frustrating because given what they can prevent – it’s probably overall a lot less of a cost to the medical system than ending up back in hospital or needing more medical intervention.

CD: There are other approaches to treating cancer now. Germany, Europe, and other parts of the world are integrating complementary practices that are seen here as alternative. They are just part of their standard practice. I get frustrated with doctors that completely dismiss anything that is not part of their western kit bag. Unfortunately because of the weight they carry, people are scared to go against their advice and they dismiss it as well. It takes courage to try things doctors don’t support.

‘Unlike football, cancer is an opponent that never rests … you have to bring your best game’

HM: Diet, alcohol, acupuncture – do you keep adjusting things to keep managing your disease?

PD: Constantly. Everything you do has an impact. You must be in tune with your body and most importantly get rid of stress in your life. It’s like being a footballer again. In the back of your mind everything you do or put into your body you are thinking about the effect it might have on the cancer, as opposed to when you’re a footballer thinking about the effect on your performance. All those one percenters can make a difference. What you eat, how much sleep you get, going alcohol-free, a positive attitude, being disciplined about taking your supplements, exercise, being willing to try new things for an edge. Unlike football, cancer is an opponent that never rests – its there 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. You have to bring your best game to have any chance against it, particularly stage four.

HM: We do all this when we’re sick – we should probably be doing it while we’re well.

PD: That’s the lesson. The part of this journey that is the hardest, is the whole emotional, spiritual part of it. That’s the last frontier. I’ve always been a black and white type of guy. But I understand how powerful the mind is. I have a good mate I met 30 years ago, and he’s led an interesting life. After his own physical challenges he’s done a heap of investigation and now helps sporting and business corporations find their edge and remove mental barriers to performance.

CD: He has been on a journey of exploration around the world, trying to understand rituals, spiritual belief, how people create their own luck, and what it is within them that creates that. There are stories where soldiers just miss being hit by a bullet by millimetres because they moved at the last second – but what was it that told them to move? He is a real believer in getting in touch with your intuition, releasing emotion, tapping into your spiritual side.

HM: How can you learn from that?

CD: The pancreas is apparently the place where you hold a lot of emotion. That makes a lot of sense. For all Paul’s calmness, he has had some big events in his life, and simply being human, there’s got to be some sort of emotional response. Paul is very stoic – but it’s got to go somewhere. I really believe addressing that is a big part of healing.

HM: You’ve had some fun with it.

CD: We took a caravan trip up to Byron, and as fate would have it, we met a lady at Wategos Beach. She introduced us to this guy who was a successful jeweller from Sydney, and he’d had a brain aneurysm. He told us this whole story about how he was meant to die if he didn’t have an operation. He didn’t want an operation, he meditated and focused on healing himself. That’s his thing now. He is on a spiritual journey, and he shared that with us.

‘I don’t have to accept the prognosis that I’ve been given’

HM: The mind can be a powerful force.

CD: We’ve just kept meeting these people along the way. Irrespective of whether you believe it or not, he didn’t want anything from us. It’s not like he was trying to sell us anything, he was just sharing his story, and it starts to open your mind to the fact that there can be different outcomes to what medical professionals tell you. It gives you hope which is so important.

PD: I don’t have to accept the prognosis that I’ve been given.

CD: There are miracles happening all around us. Whether you want to call it a miracle, spontaneous healing, radical remission – those stories are out there. Once you start opening yourself up to looking for them, you meet these people. We went to Mullumbimby, and there was a crystal shop. To see Paul sitting in a chair with crystals around him, indicated to me how willing he was to try anything – within reason.

PD: Things have changed; here I was in Mullumbimby, carrying my man bag, drinking zero alcohol beer, and sitting in a crystal chair – who cares if it works or not, what have I got to lose trying it? As well as asking for healing in a crystal chair, I’ve sat in thermal springs in WA and NT which locals believe have healing properties. I’ve been prayed with in a cafe in Kununurra. I’ve walked bare footed on the local golf courses and “forest bathed”. I spend a lot of time walking by the beach, especially at sunset. I’ve seen more sunrises in the last 11 months than any other time in my life. I’ve embraced Wim Hoff breathing and I try to meditate. I’ve met sharman’s, aboriginal healers, wizards, who continually surprise me with their insights into aspects of my health. This experience has opened my mind to other aspects of life. I’ve also got a new appreciation for nature and the simple pleasures in life.

‘I’ve seen more sunrises in the last 11 months than any other time in my life … I’ve met sharman’s, aboriginal healers, wizards’

HM: To the operation. You were told at the start inoperable, and no point. You met someone who thought that wasn’t right.

PD: The best way to get rid of cancer is to chop it out. But I think they say it’s inoperable because generally they can’t remove it all and it’s metastised so it’s already on the move. And recovery means you can’t have chemo, which when it’s palliative, you need.

CD: We met with this professor who was a surgeon. I only reached out to him because he’d published some research that I was interested in. He’d also set up a pancreatic cancer foundation – Pancare. We were looking for a foundation to align ourselves with, so we went to meet him, and as luck would have it – another passionate Hawthorn supporter! In our conversation about the research, he turned it around to a conversation about surgery. We said, “We’ve been told surgery isn’t possible”. He said, “I’ve looked at your scans, and you’re getting a better result from chemo than you might have been told”.

HM: What were you being told previously?

CD: That there wasn’t much change. He said, “My colleagues would say it’s crazy for me to even say this, but maybe there is a chance one day I could operate on you”. We heard him, but it didn’t really register. We had never considered it as an option.

HM: But?

CD: He presented it to a multidisciplinary team at his hospital, and they came back and said, “Not now. We have to wait for six months and see what happens”. I have since found out, that waiting six months was to see whether cancer spread to other places.

HM: And when six months passed?

PD: We didn’t get to six months. I ended up having two near catastrophic internal bleeds. Emergency ambulance to hospital, lights and sirens and Cherie being told I might not make it.

CD: When this happened I reached out to Mehrdad the surgeon again. He was able to look at Paul’s scans, and diagnose what the problem was very quickly. He said, the only way to fix it was to get rid of the blockage in the spleen. He needed to remove the tumour in its entirety, which meant half of the pancreas as well as the spleen. He put Paul’s situation to the multidisciplinary team again, and this time they said: “It’s the only way we can save his life now”. If he hadn’t have had it done, he would have just bled to death.

‘I’ve got a new appreciation for nature and the simple pleasures in life’

HM: The operation went ahead … and?

CD: Paul has defied all the odds. With the extent of surgery that he had, we were originally told he should be in hospital at least a week – maybe two. He was out within five days. Three weeks later, we flew up to Darwin to recuperate in the warmth. It feels like a miracle.

HM: It sounds like a miracle.

PD: At the time it didn’t feel like a miracle – it was bloody painful. In the end I had part of my pancreas removed, my spleen, my gall bladder, my appendix and part of my liver, effectively removing most of the cancer and stopping the cause of the internal bleeding.

CD: And the good thing is, his cancer markers which give you an indication of how active the cancer is, are low again. He still has a few spots left on his liver, but based on the pathology of the liver tumour that they did remove, the cancer was mostly gone. Whether that was chemo, whether that was some of the alternative things that we were doing, we don’t know and we don’t care, but we are mindful that with pancreatic cancer, given its aggressive nature, it can come back with a vengeance. We still have that hanging over our heads, but I am still researching options and staying positive.

‘I had part of my pancreas removed, my spleen, my gall bladder, my appendix and part of my liver … I’m not scared of dying, I’m not worried about dying’

HM: Paul, are you scared of what lies ahead?

PD: I’m not scared of dying, I’m not worried about dying. The reality is, and I’ve said this to the kids – when I was lying on the trauma table and I had a nurse each side pushing hard on the bags of blood to get it into me quicker, I thought, this is a bit more serious than I thought. All I did was focus on what I needed to do. Let the experts do the job. If my times up, my times up. There’s not much I can do about it. I was talking to one of my sons and he said, “How did you feel?” and I said, “I just feel for you guys. At the end of the day, you’re the ones that are going to have to deal with it when I’m not here”. Me dying is sadly their problem, not mine. That’s the reality. When I’m gone, I’m gone.

CD: I want to try and protect my kids from that. I don’t want them to lose their dad, and I don’t want to lose my husband. Even though I get a lot of positive feedback from people, and it’s nice to receive, I’m motivated for selfish reasons. I want this man here with us. Our dream was to retire and travel the world together. We enjoy the same things, our life together is great. I don’t want to be here without him.

PD: The reality is, too many people in this situation focus on the dying — and forget about the living. Really, that’s what it’s all about. Life is about living. I look back, and I’ve had a great life. I’ve achieved a lot, I’ve had wonderful experiences, and there are things I still want to do. In the end, the fear of dying really is fear of missing out.

‘The reality is, too many people in this situation focus on the dying — and forget about the living. Really, that’s what it’s all about. Life is about living’

HM: You just want more time …

PD: That’s it. More time to do things I should have been doing. Time with the kids, time with Cherie. Time with friends and family.

HM: And it takes this to remind you – and us all.

PD: And it shouldn’t. So if you are reading this, don’t wait to do what you want to, and with who you want to. It’s not a rehearsal. I remember reading an article years ago where this reporter was talking to someone in the slums of India. She said, “How can you be so happy? You live in absolute poverty, you’ve lost children, and your husband has died”. She said, “That’s the problem with you people. You always look at what you don’t have, not what you do. Have a look around, there’s people worse off than me.” I have taken that approach. Yeah, I’ve been dealt a shit hand, but really, there’s people that have had been dealt worse hands than me. Just recently, a family friend’s 17-year-old son passed away in his sleep unexpectedly. They still don’t have an answer. And a month after my bleed, and totally unexpectedly my 59 year old brother-in-law Bully just had a brain aneurysm and passed away. No one ever knows what is around the corner, so you’ve got to enjoy the present. Focus on the little things, and the joy in everyday life.

‘You’ve got to enjoy the present. Focus on the little things, and the joy in everyday life’

HM: One final message to those reading?

PD: Take control of your diagnosis and only worry about what you can control. At the end of the day, what we have realised most, is the doctors are giving you their opinion, but you have control over how you handle that. Live all your days with positivity and with the people you love around you.

CD: In a situation like this you can either lay down, cry and make it a miserable experience for yourself and everyone around you, or you can try and get the best out of every moment. Live with hope and joy. That’s our philosophy.