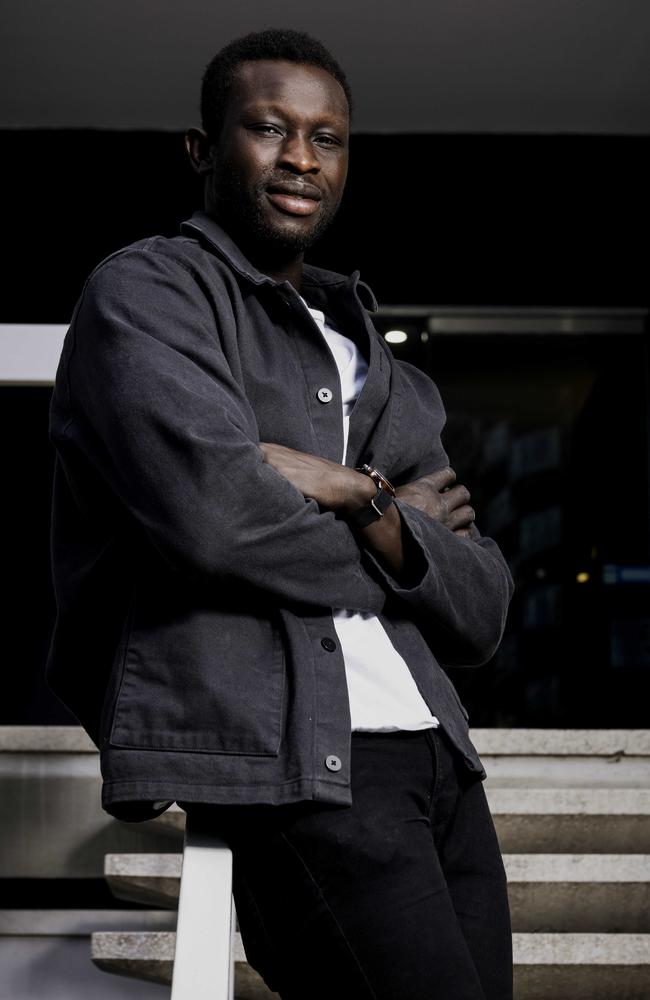

Majak Daw reveals torment before Bolte Bridge suicide attempt

At seven he fled his Sudanese village in the night and at just nine started full-time work. He has endured racist abuse and attempted suicide. Now a father, Majak Daw has found happiness.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“From feeling dead and trying to be just that, to alive again”.

This is the raw, inspiring story of Majak Daw, as told to Hamish McLachlan.

It has been a long and at times tortuous journey from Daw’s hometown village on the edge of a sandy desert in Sudan, to the hallowed turf of the MCG as an AFL player.

This is a man, who as a boy aged seven, fled his Sudanese village with his family in the dead of night and at just nine, started work full-time in an Egypt factory to put food on the table.

He has endured a lifetime of vile racist abuse and bullying.

He has also survived a suicide attempt, after plunging from the Bolte Bridge in December 2018 and shattering much of the lower-half of his huge body.

Two-and-half years later, Daw’s body has mended, he has returned to the football field, he is a father and, most importantly, happy and finally “at peace”.

Certainly, he is grateful to be alive.

Majak’s miracle

HM: Maj, did you write the book for you, for others, or a bit of both?

MD: Initially I was really hesitant about writing a book, for a long time actually, and it’s taken a good three years to finish it. But having done it, it’s put my mind at ease about a lot of things. I’ve been as honest as I can be, and completely raw about so many of my experiences. There’s some really personal stuff in there. And now it’s done, I’m glad I’ve done it. I’m glad I’ve done it for me, as it has helped me get comfortable with a lot of things, and I’ve done it to help others.

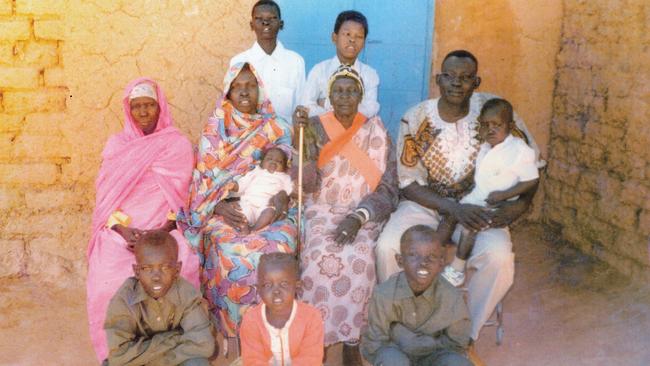

HM: Let’s go back a while. You’re one of nine kids. Were all of you born in Sudan?

MD: Seven of us were born in Sudan, and two along the way. One in Egypt, and one in Australia.

HM: What do you remember about Sudan and life there?

MD: It’s funny what you remember. I remember I’d get up really early for school, but we were done by midday! I’d have the Fridays off, go to school on Saturday and have the Sunday off. I remember living with a lot of my family and seeing them on a regular basis. We lived just on the outskirts of Khartoum, so the desert was just next door! I spent plenty of time with my grandparents.

HM: Did you know that it was a country that you were going to flee from? Did you feel like you were in an environment that you needed to get away from, or were you too young and oblivious to it all?

MD: I had no idea and didn’t know for a long time. It was all I knew, so I didn’t know what other options were out there. We left in the darkness, in the middle of the night, my mum, my siblings – I had no idea dad wasn’t coming with us. I was seven years-old. There had been talk about fleeing for a while. Leading up to it I was told to get a haircut and we bought some new clothes. I didn’t grow up with a TV so I didn’t really see how the rest of the world was living.

HM: What you saw around you was all you knew?

MD: Occasionally we’d walk past a milk bar in the neighbourhood and they might have the TV on – that was our insight into the outside world. Every now and then they would talk about Egypt, but I didn’t understand why we would pack up and leave everything we knew.

HM: How long were you in Egypt for?

MD: We were there for three years.

HM: Is it true you ended up with a full-time job to help pay for food for the family?

MD: That’s true. I worked pretty much full time as a nine year-old in a little factory. My family was poor. Dad wasn’t around, and mum had my little brothers and sisters to look after.

HM: What was your job?

MD: I worked in a carpentry store. They’d make chairs, little couches and tables.

HM: Did you enjoy it?

MD: No, I was actually bullied quite a bit there. They’d say, “go make us some tea”, and then they’d slap me across the head. I never complained, I never said anything, and I never retaliated. One day I’d had enough, so I moved over to a sewing factory where they made curtains, and tailored clothes. They really took me in as their own. They had so much love for me.

HM: When you are working full-time in Egypt, were you going to school at all?

MD: No, I didn’t go to school at all for the first year.

HM: Just put food on the table?

MD: Yeah, and we were really happy because it put mum at ease. She didn’t need to stress about food bills. We were sharing the house with other family members and at one point, there would have been four or five families living under the one roof.

HM: What does four or five families add up to people wise, and how many people are sleeping in the one room?

MD: There were more than 20 of us in a four bedroom apartment! There’d be mattresses on the living room floor, and you’d just sleep where there was space. In the middle of the night, you were in trouble if you needed to go to the bathroom. You’d be trying to avoid stepping on someone. That’s all I knew.

‘When I got to Cairo, racism arrived into my life and hasn’t left’

HM: Just on the racism. You wrote in the book you sensed danger was lurking around every corner in Cairo. Had you experienced anything like it up until leaving Sudan?

MD: I didn’t know racism at all until I stood out in Egypt when we left Sudan. When I got to Cairo, racism arrived into my life and hasn’t left. It was tough being singled out for my skin colour. I was being called a monkey on the street, and found myself running away from people trying to harass me. It opened my eyes and for the first time made me realise I was different from a lot of people.

HM: Were you across racism as a concept, or was it the first time you’d been introduced to it and couldn’t understand it?

MD: I hadn’t heard the term and couldn’t get my head around it. It was pure hate and violence. At times, that meant people putting their hands on you. I remember my uncle telling me: “You just have to cop it – don’t retaliate.” He told me that if you retaliate, you risk being killed, and if I was to get myself in trouble and an adult came to my aid, they’d be thrown in jail or sent back to Sudan. It was all pretty confronting.

HM: There’s an underlying theme in the book about having a constant feeling of being unwelcome, and not belonging. Does that exist for you now, or has that been overcome?

MD: It’s been overcome. Football has been incredible in overcoming that sense of isolation. The love that people in footy have shown me, it just outweighs all the experiences of racism that I’ve endured. I feel like I belong. I never feel any different to anyone else inside the club. I never feel my skin colour has anything to do with it anything. I love how football clubs are just one big family and are so inclusive.

HM: When you arrived in Australia, you were 10 and didn’t speak a word of English, and had no understanding of our culture. It must have been quite intimidating?

MD: It was. We came here on Australia Day in 2003. Mum thought Australia would be so cold before we left Egypt so they had gone and bought us all these puffer jackets!

HM: But you arrived the middle of January?

MD: We landed at Melbourne Airport and the first thing that hit me was the oppressive heat. It was so hot. We lived with a family of six for three weeks before we settled into our own place. When you get here, you receive a welcome package. In that welcome package when we first got to our house, there was a Collingwood scarf!

HM: They tried to convert you early!

MD: Yep! My dad had been a schoolteacher all his life, so he could speak English, but we couldn’t. I went to an English language school centre and the younger kids went to primary school. It was tough for the first month. I could say “hi’ and “goodbye” – very basic stuff. My dad made sure we read every day when we got home from school. In the morning we’d take the bus to school, and there were all these new experiences we just weren’t used to.

The beginnings of a footy career

HM: One day at MacKillop College you were invited to have a kick at lunch time, and as a result of whoever asked you, your life went down another path.

MD: MacKillop is when it all really opened up. I was still very shy and my brother and I were really unsure coming to such a big school. A few of the guys that I’m still really good friends with, embraced us at school. It was incredible. They reached out to me, let me in, and my world changed. They’d kick the footy with me at lunch time, and they quickly realised I could play.

HM: You played for the Western Jets. Your parents weren’t absolutely sure you should be playing footy though?

MD: No, mum has never felt comfortable about footy and me playing it – even to this day. She is always worried that someone is going to get hurt. She’s always telling me to be careful, and telling dad that I shouldn’t be playing. They say: “It’s too violent!” Mum would see me roll an ankle and just go off at me! She will be glad when I’m done.

HM: You went from never having seen a footy, to getting a few touches and realising you might be OK. Then in the 2009 rookie draft you were picked up, and you go from a no-name high school student to a public profile. How did you handle that?

MD: At the time, my dad had gone back to Sudan to work and see family. It was a lot to get my head around, as the first Sudanese Australian to be drafted to an AFL club. There was a lot of attention that came with it, whether that be media or my friends. I wish dad had been there to help me through that whole process. I needed someone to just guide me. Mum did the best she could but it was overwhelming. I’d never experienced anything like it before.

HM: The first pay cheque. How was it spent?

MD: A lot went to unpaid and overdue bills that mum had. It felt good to be able to clear some debts for mum. Some went to my brother. He would drive me from Werribee to North Melbourne and pay for the fuel so I figured I owed him. It was the first time in a long time where I could actually make a difference and help my family. That was a really good feeling.

HM: When you were drafted to North Melbourne, you didn’t have a driver’s license and you were living 35km away!

MD: My brother was working at the time, and we’d get up at 6am and he’d drop me off at the club. I would train, then he’d have to come back and pick me up and drive me home again. We did that for the first three to four weeks, before the club said: “Maybe you should come and live in a share house with the other players?”

HM: How did that sound to you?

MD: I was really scared to bring the idea up with my mum. When I did, she was not happy at all! I lived at home, she cooked, she cleaned – she did everything for me. I packed up all my clothes and she unpacked them and put them back in the closet. Aside from my older brother, that was the first time in a long time one of her kids was moving out. I was excited to have my own space and I haven’t moved home since.

HM: There is a terrible part in your book talking about your parents copping horrible racism when they got off a bus. Kids were waiting with eggs for them.

MD: That really broke my heart. I have copped it in my lifetime and there’s incidents that I haven’t told my parents about, but to see them walk in the house drenched in eggshells and egg yolk – it was hard. You could see the sadness in their faces. They looked broken.

In Australia, my parents were egged and I was called an ape

HM: Some young kids had waited for them to get off the bus with all their shopping and just pelted eggs at them?

MD: Yeah, right out the front of their house. It was all premeditated. Mum and dad kept it together but when you see it happen to your parents, people you grew up admiring and looked up to – it’s disheartening. How can people treat others like that?

HM: From all my reading, the most sad I felt was when you were talking about a VFL game in 2011 at Port Melbourne. An old white guy leant over the fence and said … and I find it hard to even say: “Go back to where you came from, ya f---en black ape!”

MD: It’s hard to hear even know. It was hard to write in the book. I was really young at the time and when you played at Northport Oval back then, it was packed. Every man and their dog would be at the ground. After it happened, I was full of rage, just in disbelief. I tried to keep my composure, but in the end, I broke down in tears.

HM: During the game?

MD: At halftime. Once I got into the rooms, I broke down. It was more the disbelief that it was still happening. Like I was telling you earlier, I loved being part of a footy club. People embraced me so quickly, so I’d never felt different but when that happened, it rattled me and reminded me that I wasn’t like everyone else.

HM: You say in the book you have always had a level of social anxiety from a young age, but it was minor and manageable. When you became an AFL footballer, because you were catapulted into the spotlight, it was more difficult to deal with?

MD: It was. I found it really hard because of my profile at the time, and how recognisable I was. I was a VFL player, I hadn’t played a game and I was quite a reserved person by nature. I keep to myself when I’m not with people I’m comfortable with. Looking back now, whether I was at an event or a party, I’d always leave early or bail out at the last minute because I couldn’t deal with being in the public eye.

‘I was drinking a lot, actually way too much … mentally very troubled’

HM: You and Emily, the mother of Hendrix, were in a relationship and you mention there was a period where you were constantly fighting and to cope you were finding yourself drinking a lot. Were you drinking more as a result of finding the spotlight of football difficult, or the relationship becoming problematic, or both?

MD: I was never a big drinker growing up because neither mum nor dad drank. In the book I talk a lot about alcohol abuse, so they will get a shock from that but it’s the truth. In the back end of 2018, I was drinking a lot, actually way too much. There were a lot of things going on that I was trying to mask. There were plenty of events around the place, the Spring Carnival, Grand Final week. People around me were telling me that I was drinking a fair bit.

‘Emily told me my alcohol consumption was concerning . . . there was enough evidence from the people around me to suggest there was a problem’

HM: They were noticing it were they?

MD: They were. I’d brush it off and say: It’s not an issue.” Emily would tell me my alcohol consumption was concerning.

HM: Did you know deep down you were drinking too much?

MD: I did. You are always try to justify your actions but there was enough evidence from the people around me to suggest there was a problem. I knew it.

HM: You went to a party in October of 2018 with Emily, and you started fighting with someone that was well known to Emily. They were saying some inappropriate things to her. You got home and started drinking. Was that the first time you tried to take your own life?

MD: It was. I was so angry. For a few hours I just couldn’t calm myself down and I was overwhelmed with everything. I tried to take my own life. That’s a scary thought and a scary way to go about things. When I woke up in the morning I wasn’t in a good place. I rang the club doctor, my best mate at the time, and another mate of mine, and told them what had happened. They all came around, and we sat in my living room for a long time and talked through it all. I then I just broke down. I was mentally very troubled and I couldn’t hide it anymore. I couldn’t make sense of things, and I wasn’t strong enough to deal with it.

HM: You went away and had some issues when travelling. You’d been speaking with your doctors, and they’d said to stop drinking. Did you end up ignoring the advice and hitting the grog again on the back of a terrible Bali experience?

MD: I came home, and I told a few friends about what had happened in Bali. I didn’t tell my parents because I didn’t know how they would react, or if they would understand. Mum and dad are very strong Catholic people. I told my cousin what had happened and he was very supportive. I was in rehab for footy surgery when I returned and I was still seeking professional help. We came to the conclusion to stay off the grog for a while. If I did drink, it would be just two glasses, no more, and not every day. I’m a high functioning person by nature and I knew how to push the boundaries. Looking back now, the warning signs were everywhere. I was drinking again, in the middle of peak summer season, and at the races and things. Too much.

Things spiralled out of control when Emily said she was pregnant

HM: And it was around that time when Emily revealed she was pregnant, and that’s when things spiralled out of control?

MD: They did. And I didn’t know how to handle it. I wasn’t quite sure if I was ready to be a father given my battle with mental health. Things were unstable and it just didn’t sit right with me. Nothing really did. I was all over the place.

HM: Was it that night after Emily told you she was pregnant that you went to the bridge?

MD: It was, yeah. Emily was around earlier. I had a big night – it was a Saturday. There was a BBQ upstairs in the building where I lived, on the rooftop. They’d invited everyone in the building to come up and Em and I had just had a fight. I needed to get out of the house, so I went up. I became very intoxicated. I came back down to my apartment, kept drinking and felt numb. I was in an awful place. I was wrapped up in my own world of darkness. I was just really angry. I tried to take my life.

HM: How?

MD: Firstly, to my wrist. I didn’t get it right, so then I attempted to hang myself. I eventually grabbed my keys and drove to the Bolte Bridge. I sent Emily a text message, telling her that I was sorry but I couldn’t stay around any longer and then I threw my phone back in the car, and jumped over the rails into the darkness.

HM: There were lots of moments to rethink, where you could have changed your mind, but the world felt so bad, you thought it was the best thing you could do?

MD: It was more about ending the pain and the hurt that I felt. I couldn’t endure it, and I wanted that to end. I thought at the time that the only way to stop the suffering was to end my life. There are other ways to manage and help that pain. You don’t have to take your own life, but I thought that was my only option. I thought it was better than any alternative I could think of.

‘I was wrapped up in my own world of darkness. I was just really angry, I tried to take my life … when I chose to jump, I regretted it straight away.’

HM: When you texted Emily, after you’d pulled over on the side of the Bolte – you just walked over and jumped?

MD: I went straight over. I was just so determined, and maybe a bit of stubbornness plays into that too. I’m so grateful that I’m still around. There are so many wonderful things in my life. Just imagine if I wasn’t around — we wouldn’t be sitting around having this conversation. I love my life now. It took going through those experiences to realise just how beautiful simple everyday things are. Some people are not as lucky as I am. When I chose to jump, I regretted it straight away.

HM: You’re in mid-air when you realised you made the wrong decision?

MD: Yep.

HM: You talk about the noise being something you’ll never forget.

MD: It was a really loud crunch. I fractured my pelvis, my back, and I really struggled post-surgery for a long time. I’d wake up in the middle of the night, reliving everything.

HM: When you hit the water from a great height, people say it is like falling on a concrete road?

MD: Yeah, you could say that. It was just an impact that I’d never experienced before and hope never will again.

Everything was just a blur … so dark outside and … I remember being so deep in the water’

HM: What do you remember after impact?

MD: Straight away, everything was just a blur. It was so dark outside and in the water. I remember being so deep in the water, and I was desperate for air. I fought so hard to just get back to the surface. I had tried to take my life, and now I was fighting for it. I blacked out for a moment … it is all so odd hearing myself say this.

HM: At that point, you’d broken what?

MD: I broke both pelvises, both hips … when I was rescued by the paramedics, I couldn’t move.

HM: With everything broken, how did you get to the surface, and then to land?

MD: I started swimming just using my arms. Everything else was either broken or not working pretty much. Looking back, realising how close I was to one of the poles that holds the bridge up, I was so lucky. I missed it only by a few metres. It would have killed me immediately.

HM: The emergency services arrived so quickly.

MD: I have no idea how, but I’m really grateful that they got there so quickly. They were there to save me when I got to the bank. Incredible really. How lucky am I to be here …

HM: Very mate. I understand your mum and dad were really affected. They couldn’t believe that one of their sons would try and take his own life?

MD: Mum and dad were really hurt.

HM: You’d been putting on a brave face. They weren’t aware?

MD: They didn’t know anything. That was the biggest hurdle for them to get over – that they were some of the last people to find out. My dad and I had had a fractured relationship for a while, but he just couldn’t get his head around it. As a father now, I just want to protect Hendrix at all costs and be there for him in whatever he’s going through. I want to build an environment where he feels OK coming to me and asking for help whenever he’s struggling. Whatever it is, we’ll work through it. Emily was hurt the most. She is a strong woman. She’s been through so much pain because of my actions. She has just been so selfless in her support. She just wanted the best for me. I really let her down.

HM: What would you say to those that are battling with depression, and struggling to find a way to wake up tomorrow?

MD: Start with your family and friends. People you trust. Then seek professional help. Mental health is very strange, not all struggles are the same, and all challenges are different. A professional understands what you are going through. It requires work. You need to tell them what’s going on, and they’ll help you, and give you the right tools to regain your strength and get you back on track. There’s no judgment, it’s confidential – it just requires courage. Be strong.

HM: From the bridge, back onto an AFL field. That seems so implausible.

MD: I don’t know if I’d be able to go through any type of rehab like that again. It was incredibly hard. I thought I’d go home after surgery but little did I know the people around me were quite nervous, unsure if I would ever walk again, and as a result concerned I would try and take my own life again when I was told the news. I had an enormous amount of people come and visit me in hospital.

‘From feeling dead and trying to be just that, to alive again in so many ways’

HM: Did that help you? Make you feel loved and glad you hadn’t taken your own life?

MD: People were heartbroken, which gave me a sense of love. And because everything was so public, I couldn’t hide, and I couldn’t go anywhere, I had to address it all. In the end, I knew the only option I had was to get my life back on track. I would get my mobility back, learn to walk again, and get back on track. I’d attack my rehab in hospital. I was so immobile I was doing aquatic strengthening surrounded by 80-year old’s that’d had hip and knee replacements …

HM: And when you ran onto the ground on return for the Kangaroos?

MD: I was really confident. You have to be optimistic, because that’s the only way you get through. I ran onto the ground, and my teammates were there, my friends, my family, Emily. I was back. From feeling dead and trying to be just that, to alive again in so many ways.

HM: And you felt proud?

MD: Really proud. It was such a big milestone for me. I’m not sure people will ever understand what it took to get there. The work behind closed doors, not being able to train with my teammates, the sleepless nights at home, the physical pain I was in. I was really proud to have got back to where no one thought I could, and back to a place where I was happy.

HM: To the reason you do it all now. Hendrix. He’s the miracle from all of this?

MD: I’d do anything in this world for Hendrix. My mum and dad have sacrificed their comforts, their jobs, just for me and my siblings to have a better life. I admire them so much. Hendrix came along, and he’s so full of character. He’s very energetic. My dad didn’t really show me too much affection growing up. I knew he loved me deep down, but with Hendrix, I’ll kiss him every day and tell him I love him. I get the biggest joy out of being his dad. One day, when he is old enough, he will understand what I went through, and how much of a factor he was in getting in my life back on track. I hope if he ever struggles or goes through anything similar to me that he doesn’t have to endure or struggle as much as I did. He is the miracle, he is really my saviour.

‘My son is my miracle, my saviour … I’m at peace’

HM: Hendrix is lucky to be so loved. Are you happy now?

MD: I’m happy. I enjoy the simple things in life now. I’m at peace. I love playing footy, and I love having the opportunity to still do what I do. I love being there for Hendrix. I appreciate little moments throughout my day, throughout my week, things that give me joy. I’ve learnt that you can’t be happy all the time, and that’s OK.

HM: Mate, the book is a tribute to a life full of complexity and I loved reading it. You should be unbelievably proud of where you’ve been, and where you are.

MD: The book is very raw, and very honest. It will be something I really appreciate when I’m a bit older. Once people get a copy and start reading, hopefully that’s when we can start to make change.

Majak by Majak Daw with Heath O’Loughlin, will be available in print and audio from August 3.

If you or someone you know needs help call: Lifeline: 13 11 14 Beyond Blue: 1300 224 636 Kids Helpline: 1800 551 800