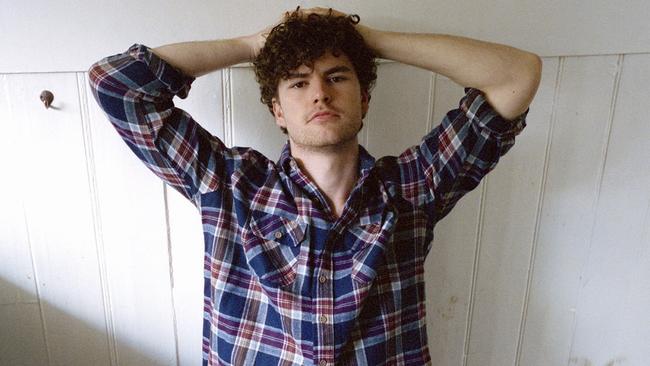

Hamish McLachlan: How international hit Riptide changes Vance Joy’s life

Vance Joy was a talented high school footy player who took music lessons on the side. It wasn’t until he wrote his first song that he became addicted to music.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

He was christened James Gabriel Keogh, but is known around the world as Vance Joy.

He played VFL football for Coburg and was school captain at St Kevins. Musically, he is largely self-taught, but keeps writing hits.

He has produced music that has been streamed five billion times. His third album – In Our Own Sweet Time – has just been released.

He has toured with Pink and Taylor Swift, is playing at Big Freeze 8 on the Queens Birthday and is on high rotation on my playlists!

It would be hard to find a nicer bloke to talk to than Vance Joy.

HM: Your mum was an English teacher, your father a software engineer. Could either sing?

VJ: They both had their own style of singing. Dad would walk around the house singing a lot, but never explored it. He can project and hold a tune. Mum doesn’t have quite as strong of a voice, but has a nice vibrato effect on her voice, which I joke about with her. She can also hold a tune. They don’t play instruments, but they were adamant that we would play instruments as kids.

HM: What was the first instrument you picked up?

VJ: Piano. I was in primary school, and we got piano lessons from Mrs Runge down the road. We’d walk from school to her house and we’d have cordial, biscuits, and a lesson. Then we’d walk back home after we were finished.

HM: Did you enjoy it, or were you forced to do it all?

VJ: Forced to do it. She was lovely, a sweet old lady, but because she was so nice, I didn’t do the extra work! It was theory, but mostly I just did it by ear. She said to my parents, “He has a good ear, but he’s not interested in the theory.” If there was a song I liked, I would watch her hands and memorise them.

HM: So there was clearly something musical within?

VJ: There was something there for sure, it just wasn’t as obvious to me then as it might be now looking back.

HM: When did sport take over? You were school captain of St Kevin’s, and I’m told, a good defensive tall as a footballer. Is that right?

VJ: That was where I was most comfortable on the football field. I played in the firsts when I was in year 11, and played a bit in the ruck. I don’t think I ever won a ruck contest, but I was put in the votes because I was undersized, and I was competitive against much stronger schools. It was more of an encouragement thing. When I became a defender I just used to follow the forward around, and eventually I’d get a few marks or kicks that way.

HM: You were good enough to play VFL football and be with Coburg for five years. Did you think at any stage you could play at AFL level? Or were you a rung below?

VJ: In the first year I was very excited because Andrew Collins, who was coaching at Coburg, said to me, “What do you think about playing AFL football?” I’d just been playing at St Kevin’s Old Boys! That stoked the fire for some sort of ambition, but for that first season I played in the reserves all year. We won the flag. It was a good team in the reserves – there were a lot of super-talented players that went on with it. In the second season I played half the year in the Ones; we had Jade Rawlings as coach, and I had a decent season. I was playing that defensive backline role, but I was a bit complacent thereafter. I hadn’t figured out with football that I had to be mentally committed to perform each year, and that’s when the interest in music started to take over. Footy was cool though. I got to play with a lot of great players.

HM: If someone said to you in your second year of uni, “What’s going to pay the bills?”, would you have said law, football or music?

VJ: I would never have thought that music was something that would pay the bills. I had very vague ambitions and dreams when it came to music, and I really just fell into it. I loved to play guitar and play covers, I enjoyed singing, and when there was an opportunity to sing a cover for people, I’d do it. I’d perform at the Coburg Football Club functions.

HM: Voluntarily?

VJ: Sort of. It was a bit scary, and I was reluctant, but I would get up and play a cover. I always got a good reception for it, and people would often tell me to go on The Voice.

HM: You hadn’t had a lot of singing coaching, you hadn’t had a lot of music lessons – it was all natural?

VJ: Singing and playing was just a natural thing. I did do guitar lessons for three or four years in high school, but that’s just to learn the basics, to develop some techniques and good habits. I had a great teacher named Vince Hopkins, who was awesome. I’d never had any coaching in singing, but I think that’s a good thing.

HM: Because?

VJ: As soon as you go to a singing teacher they’ll say, “This is how you breathe, this is the proper way to breathe in between singing, this is how you should pronounce your words”. The way you pronounce your words is the unique thing about you, you don’t want anyone having too much of an influence on that. I kept playing guitar here and there, and when I was 21, I wrote my first decent song. A song called Winds of Change. I remember writing that song, and I got a rush. I had chills. I felt like I was channelling something. Any opportunity I got, I’d show that song to someone. That got the ball rolling. I stopped playing VFL, I went on a backpacking trip, and for that whole trip I was imagining songs and ideas for lyrics. I came back with more of a resolve to do song writing at the start of 2010.

HM: 2010 was your first gig, at the Great Britain Hotel?

VJ: Yeah, that’s right. I started playing at open mic nights when I got back, and at the end of 2012 I wrote Riptide.

HM: Were you terrified when you get up at the Great Britain?

VJ: Absolutely terrified. That was my first open mic night. I arrived there earlier in the evening to put my name down on a list, and I forgot my capo, which is something guitarists use to hold the strings down. I had to quickly get in the car, drive back, and then drive back to the Great Britain. My girlfriend at the time came with me, and I was so nervous. It was a room with three people in it, but I was terrified!

HM: And now?

VJ: I feel so much more comfortable now. I’m going to do a radio gig later and there will be people there, and it’ll be enjoyable. At that point at the Great Britain, it was terrifying. I was waiting for people to get through their songs, and I grabbed a glass of white wine. I’d seen Kings of Leon at Falls Festival around that time, and in between songs they were sipping on what looked to be white wine. I thought, maybe I should do it! My mouth was already dry, and the white wine made it even drier. I’d written lyrics on the inside of my forearm, in a marker, in case I forgot them. There was no way I could read them if I needed them … I was so nervous that my brain was short circuiting.

HM: You said you went backpacking and started writing songs, visualising songs, seeing songs. Something like Clarity, or Catalonia, or Riptide, or Fire and the Flood – how do they emerge, and how long does it take to get it on paper? What’s the process?

VJ: Most songs have a long journey. Using Riptide as an example, I wrote the first couple of lines of the verse without thinking. I sang the first few lines of the verse in 2008, and I didn’t think anything of it at all. It laid dormant for a long time. By 2011 I was playing on this little ukulele I had, and while I was playing a ukulele riff, I thought, “Hey, this fits over the same three chords that I was playing in 2008”. In the space of a couple of days, all those connections were made. I realised that I could stick these three different parts together, and they would hold together and be a song. It might just be a few different parts that can fit together, but once you do that stickytaping of the different parts, the magic happens.

HM: So it doesn’t necessarily happen easily? Like a big puzzle, you come back to it over time, when you feel like it, and you get it done in the end.

VJ: Yeah, it does for me at least. It takes time. Riptide was a big stream of consciousness with the lyrics, but it was still separated by several years. The same thing happened with a song called Georgia. I had a guitar riff, and I wrote a whole song with my mate, Nick Murphy (Chet Faker), who lived down the road. He wrote a song using that guitar riff, and then the right verse and melody came along. That was in 2014, still separated by three years. Clarity was a bit different. I had the voice memos in my phone, but before I went in and did a songwriting session with Joel Little, who I wrote the song with, I would look in my phone the day before and I’d just listen to all my voice memos just walking around. I’d just think to myself, “Does that fit with that?” I came up with three pieces that would fit together, then we got on a zoom, and I showed him. What happens if you put that bit, into that bit, into that bit? Getting the raw ingredients is the long part, accumulating enough of those takes time, but once you stick them together, it’s quick.

HM: Shane Warne spoke to me about “The Gatting ball”. He said, “It’s funny how one delivery can change your life forever.” The Gatting ball did that for him. Did you know that Riptide would for you? Did you think you’d written something that would be streamed billions of times?

VJ: No, I didn’t know it was going to be a life changer. It’s the song I came out of the gates with, the first song I’d ever properly recorded, and I had no idea that it would be streamed billions of times. I did feel it was a bit special. I remember I was at university, and I was doing a summer class to finish my degree. I was writing some of the lyrics for the chorus of the song in the margins of my notes at uni, and I was walking to my car in the carpark, and I thought to myself, “I’ve got a lump in my throat, because you’re gonna sing the words wrong”. That was the last missing piece of the puzzle. I drove home, picked up the guitar, played it, and it fit together. I played it to Mum and Dad, and they’re usually stoked to see me play guitar, but it really connected with them. I got that same response every time I played it. I knew it was going to get that response from people, I just didn’t know at what level, but I knew it would work.

HM: Is it true that you paid, to record the single, a princely sum of $700?

VJ: That is true. I had some family friends who were in a band – my dad’s best friend Rob, and his four sons. The Red Aces. I looked at their Facebook page, and they were in a proper studio. I saw the studio was called Red Door Sound. I went on the Red Door Sound website, I called the guy, and I kept bothering this bloke called Woody who ran the studio. He’s a sound guy for some big artists, and he was on tour. I was calling him, pestering him, and he eventually gave me a day. $700 it cost me. That also pays for the sound engineer, a guy called Tyson. Me and my drummer Ed went in at 10am, and Tyson did the engineering. We finished at 3am. Now I can play the click track well, a click that’s in your ear to keep you in time, like a metronome, but when they tried to put the click on initially, I was all over the place. I could not play to a click – I’d had no experience with it. I remember driving home that night, and I was falling asleep in the car because it was such a long day. I got home at 5am. There’s something cool about doing it all in one day, making those decisions quickly. When we’ve had more time and money to do recordings, something is lost. It’s nice having such a tight restriction, because we decide in the next 10 minutes what the drums are going to do. That’s some of the magic in that recording, and it’s been hard to beat.

HM: How did you earn the $700?

VJ: My friend’s dad, Pete, has a gardening business in Camberwell and surrounding areas. That was a great job. I did that a few days a week and started work in a call centre for Open Universities. I had enough money to record the first song, and I had enough money to pay for the film clips, which cost a few grand. That’s where all my money was going at that point.

HM: Most of us want to be a rock star … well, I do. What’s it like to walk out and play before Pink, or Taylor Swift, or at the AFL Grand Final in 2016 with Sting? What does it make you feel?

VJ: Now, it’s very cool. It’s a great electric charge. It’s a real rush running up behind the mic and waving at the crowd to start a show. When I started, I’d stand up there and look at my feet and just get through the songs – I was so unsure and nervous. But I feel like the more I do it, the more I feel really present and the more I can connect with the people in the crowd. It’s not like I’m doing that much, I’m just playing guitar and singing but I feel much more at home on the stage now.

HM: Is performing live in front of a big crowd still the best of it all?

VJ: Yeah, absolutely it is. To put it into context, we did a week of rehearsals and sound checks, with no people watching, before this first festival show last week. There’s no vibe, and I don’t know what my voice is going to be like. I can’t get into it. There was none of that passion and energy you find in front of a crowd, your bloods not pumping, you’re not amped up. But then as soon as I got on stage, it was better than ever. It’s just so cool. I hadn’t thought about how good it was over the past couple of years, because it wasn’t a factor, or an option to play live. Playing live, and writing the songs, that’s why I do it.

HM: I assume the touring life is fun in part, but not quite as glamorous as it seems.

VJ: That’s true. It depends how rigorous the promo schedule is. I experienced crazy promo schedules when Riptide came out and we were opening for Taylor Swift. I would have crazy promo days most days. It was finally like work, but I was still having a great time. We got to open for Pink, and there weren’t many interviews to do as it was at the tail end of an album cycle. When Riptide first came out and I was opening for Taylor Swift, I was much more in demand. The upside of not being that in demand is you have days off, in Europe … you’re on a summer holiday and play the show every two or three days. You play before Pink, you get to watch her, you invite your friends … it’s pretty surreal.

HM: With writing songs, do you feel a weight of expectation to produce these wonderful songs? Is writing painful, pleasurable, nerve-racking, or a mixture of all of it?

VJ: A mixture of all of it. There’s a bit of pressure … if you don’t keep writing hits, it’s an issue. It depends how much pressure you put on yourself too. When I first went into the Atlantic Records studio in 2012, I met the top dog, Craig Kallman, and I was super nervous. I played a few songs in his office to him, and he said, “This is great. Give us a few more Riptides”. I said: “OK … I’ll see what I can do!”

HM: No pressure though …

VJ: No pressure … A couple of times I did songwriting sessions with bigger songwriters that have had numerous hits. I got to work with Benny Blanco, who’s a hit-maker from America. It was cool walking into that studio. We ended up writing Fire and the Flood together. I’m proud of that song, but it was a scary experience. I’d never collaborated with anyone before, and suddenly, you’re in this room with these people that do it regularly and have had a lot of success. When you’re nervous, when you’re prerecording verses live and you’re in a scary situation, something cool often happens. It happened with Joel Little when I wrote Missing Piece with him – it will get you out of your thinking mind, and you just let it flow and you tap into something. I do like trying to step out of the comfort zone to try new things.

HM: Your third album, In Our Sweet Time, is about to be released. A lot of new songs as well as a couple that we know. How many hit the edit room floor and never get heard?

VJ: That’s a good question … there will be seven or eight that aren’t on this. Often, they are the product of a songwriting session. Some are decent songs, it just really comes down to choosing the best 10, 11, 12 songs. There are those cutting room floor songs, and then those you write that’s a good song, but you write it with someone that doesn’t speak on the same wavelength as you are lyrically. You might have a song, and you’re singing it in the demo, and you realise, “This doesn’t really feel like me”. I feel like the people that know the music will identify it straight away. If I’m not feeling it then they’ll recognise it immediately.

HM: Have you ever forgotten lyrics on stage?

VJ: Yes, it happens often enough to be truthful! It’s a good opportunity to break the tension in the crowd or have a funny moment. I will look around at the band, I’ll look at my drummer, Ed, and he’ll give me the cue. It’s the old songs that you don’t play very often. I never thought I would forget my own lyrics, but I have!

HM: If you could play one gig, anywhere in the world, to a full house, where do you play?

VJ: There are these famous venues, like Red Rocks, Madison Square Garden. These places that feel like a rite of passage. They would be cool. In Australia, the steps at the Sydney Opera House would be awesome with a full house. Radio City Music Hall, in New York, is another iconic one. I’d take any of those!

HM: Grand Final 2016. Who puts their arms around you, and what do they whisper?

VJ: Ahhh! That was after we performed. We got off the stage and went back to the green room. It was an electric event to play at. The crowd is a fair distance away, it’s being broadcast on telly, and you can’t have anything go wrong, or it’s going to be a memorable failure. We were sitting in the green room, and all the music had ended and the footy was about to get going again. Two arms came around me, and someone whispered, “Well done”. It was Sting. Everyone went quiet on the table just as he stood behind me, there was a change in the temperature. What a lovely dude, such a great inspiration. That was a special moment.

HM: Favourite track on your third album, In Our Own Sweet Time?

VJ: Don’t Fade.

HM: Essendon. You are a fan …

VJ: Love them. I haven’t been watching many games with being away, but they’re getting battered, though. I’ve been keeping up with all the footy shows and read everything … hopefully we get some run and attack and confidence going soon!

HM: You went to school with Chet Faker and Generik. The three of you are all known by names that aren’t yours! You settled on Vance Joy. How did you end up with it, and what were the options if it wasn’t Vance Joy?

VJ: It’s funny that all three of us ended up doing music. Jimmy Keogh was my first performance, and then a guy at the football club said, “Jimmy K! It’s got to be Jimmy K!” That sounded more like a DJ name. I saw Vance Joy in a book by Peter Carey. It’s scary when you start calling yourself by a stage name, you have nothing really to show for yourself. You feel a bit embarrassed. People would say, “What are you calling yourself?” Vance Joy. “What?” You repeat it so many times, and no one knows what you’re talking about. It worked out. I’m glad I used that instead of Jimmy Keogh, no one pronounces “Keogh” correctly!

HM: The people who know you well in your life call you Jimmy or James, and the people that don’t know you around the world call you Vance.

VJ: Correct. If I’m stopped by someone who knows my music, it’s “Hey Vance”. My mates call me Jimmy.

HM: Last one. Riptide … the lyrics “I swear she’s destined for the screen.

Closest thing to Michelle Pfeiffer that you’ve ever seen”. Why Michelle – did she just fit lyrically?

VJ: I’m a big fan. She’s right up the top. I was into Batman as most young kids are, and I watched Batman Returns a lot. She was amazing in that, the best Catwoman ever. Unparalleled. That name, in a stream of consciousness, just came out. She got in touch recently, she has a perfume fragrance brand …

HM: Called Vance?

VJ: (laughs) It’s not, unfortunately, but she sent me a sampling kit with a lovely note. She knows that I was the first person to ever name-check her in a song. There was Uptown Funk, which was a huge song, but she knows I was the first to reference her! It was cool to have any engagement with her, she’s a legend!

HM: Arts law degree, five billion streams, VFL footballer, back on tour, third album. You’re been outstanding – thank you.

VJ: Thank you, Hamish. You’re a champion. I’ll see you at the Big Freeze!