From chasing missing money, to catfishes and cold cases these are Melbourne’s top PIs

From investigating a $2bn World Bank loan to tackling cold cases and exposing catfishes, these are Melbourne’s top PIs.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Whether it’s investigating corruption tied to a $2bn World Bank loan, tackling cold cases or exposing catfishes, Melbourne’s private investigators have done it all.

The Herald Sun has combed through famous cases and spoken to industry insiders to put together a list of some of the city’s most high-profile investigators.

But firstly, what does a private investigator actually do?

The industry is as diverse as it is misunderstood, so we spoke to Andrew Patterson to find out.

Mr Patterson, based in NSW, will soon take over as president of the industry’s national body – the Australian Institute of Professional Investigators – and said their membership is far broader than the typical stereotype.

“The stereotype of the private investigator, hiding there with a long zoom lens and photographing the cheating spouses … that part of the industry does exist but the industry … is very broad,” he said.

“Most investigators will specialise in some way or other, such as my speciality with workplace investigations.”

He said while former cops, such as himself, were common in the industry being a police officer was not a prerequisite, citing plenty of excellent investigators from accounting or legal backgrounds.

“In terms of skills it’s objectivity first and foremost … a tenacity to keep going and an ability to pursue everything as far as it needs to be pursued.

“Integrity and objectivity are the key things. If you haven’t got them, you can have all the investigative skills in the world. You’re not going to produce what I would call professional work.”

He said professionalism was the “driving force” behind the institute’s work.

FORDE NICOLAIDES

Investigator Forde Nicolaides’ career as a private investigator began when he decided to study accounting at university.

While police backgrounds are common in the field, the demand for someone who can uncover a carefully hidden paper trail means finance is another popular pathway.

After his studies, he worked at a large firm in auditing before moving into insolvency, which he describes as the beginning of modern forensic accounting.

“Insolvency practices back 20-30 years ago is where most of the forensic accounting investigations came from,” he said.

“It was part of a breeding ground for want of a better word.

“A lot of that is about asset tracing, finding the missing money, looking for things that directors of failed companies have dissipated.”

With no shortage of white collar crime to investigate, his skills have always been in demand.

He worked at ASIC for seven years as a forensic accountant, reconstructing account records and tracing missing money before moving to Deloitte in the late 90s.

He’s now a partner in forensic practice there with a focus on corporate investigations.

He said his role can vary from investigating fraud, to advising clients what they can do to prevent corruption or giving evidence in court cases as an expert forensic accounting witness.

Nicolaides said the focus historically had always been on violent crime.

“I think in more recent times courts have accepted the seriousness of white collar crime,” he said.

“So you are starting to see some decent jail sentences imposed.

“You’re starting to see the regulator issuing civil penalties

“It’s better than it used to be. I remember working on cases where the maximum jail time for theft is about 10 years in jail … But people were only getting like 18 months or 12 months and sometimes they were getting suspended.

“Whereas today, that’s not the case, you’ll find that the courts are imposing some jail sentences to make it a very clear deterrent.”

Nicolaides has seen a number of changes since he began working in corporate investigations, including a rise in workplace harassment cases as society’s understanding of such behaviour changes.

“We have seen more of those cases come forward,” he said.

“Organisations have started to treat them a bit more serious.

“But there’s still room to improve for many of them … in the way they prevent and protect them.”

New technologies have also been added to the tools at investigators disposal, he said.

“Pretty much every investigation we take, we look for a technological-based solution,” he said.

“You might not think there’s much innovation in the investigation space, but there is.”

He said one of the emerging tools was voice recognition, which they can use to identify calls made to a bank call centre in a fraud case, for example.

But regardless of technological advancements, Nicolaides said human nature means the industry is here to stay.

“There’ll never be a moral awakening in the world,” he said.

“You’ll always have something.”

DAVID GRAY AND PAUL WALSHE

Interviewing players during Essendon’s infamous ASADA doping case and managing security during a 742-day industrial dispute with a global oil giant are among the cases David Gray’s firm has overseen.

A former police detective, he founded Asia Pacific Security Group with two colleagues in 2008.

The company director said their work could range from providing security and digital intelligence to covert surveillance and undercover agents planted in workplaces to investigate employees.

He described working for a Melbourne manufacturing business that suspected some workers were stealing from them.

“We inserted an undercover into the business on the relevant shift, as well as installed a number of CCTV cameras,” he said.

“Our undercover became “the eyes” of management to observe behaviour of these workers to determine the truth or otherwise of these suspicions.”

The firm’s general manager, Paul Walshe, is also a former Victoria Police detective and spent time working with the FBI.

He specialises in family violence matters, which he said “sadly continues to rise”.

“In the early stages if there is no evidence to support a claim, this makes it difficult for victims to engage with police or courts,” he said.

“So we support the victim to gather that evidence.”

He said cases they have worked on include a young mother who was being illegally tracked by her abuser.

“The husband was illegally using spy equipment and surveillance to track and spy on the wife’s movements,” he said.

“We gathered evidence of this and supported the wife through the court process where she obtained an IVO and custody of her children.

“We installed security systems in her home so she and the children could feel safe.”

He also takes on stalking cases, gathering evidence to bring to the police, and said it doesn’t just impact “celebrities or high-profile people”.

“It is just as common in the general community,” he said.

“These matters can drag on sometimes with tragic occurrences.”

Mr Gray said a law enforcement background wasn’t necessary to work in the investigations field, but it could be a big asset.

“You never know what your day will bring,” he said.

“Former police members … carry with them a high-level of investigative skill and experience.

“Often our investigations result in the detection of criminal behaviour and that’s when we may refer matters to police.

“Having an understanding of how they operate can assist with liaison and engagement when necessary.”

JULIA ROBSON

Former New Zealand police officer Julia Robson describes herself as a “modern-day sleuth minus the trench coat” who specialises in all things digital.

Now based in Melbourne, the Online Investigations director has built up a reputation for using her internet profiling skills to expose catfishes.

But she told News Corp’s new podcast Eye Spy she also looked into cold cases in her spare time, including the case of 23-year old Amanda Byrnes, who was brutally murdered in 1991.

“Every so often I will take on a pro bono job related to cold cases and long-term missing persons,” she said.

“Those are the ones that really strike a chord with me.

“I just would love for the family (of Amanda Byrnes) to get some resolution.”

Robson is arguably best known for the seven years she spent hunting down a conman and romance scammer, which she later narrated on the chart-topping podcast Chasing Charlie.

The series website reports she began working on the case in 2011 “when a woman named Vivien first engaged Robson’s PI services in the hope of tracking down her deceitful partner (who she had met online months earlier)”.

“(He) was in the wind after cheating her out of $70,000.

“Robson uncovered numerous other women across the globe who the so-called ‘Charlie’ had exploited for financial gain.”

She interviewed victims in Australia, Europe and the US before finally tracking ‘Charlie’ down to New Zealand, where he was arrested and charged with more than 30 counts of fraud.

She has also used her sleuthing skills to help those navigating the dating scene and launched Cupidscreen – a service offering background checks for potential online dates – in 2011.

Robson’s work has made it on to the small screen. has worked as an investigator on television and radio shows including Ten’s Long Lost Family, Foxtel’s Real Housewives of Sydney, and Mix Fm’s weekly segment ‘PI Case Files’.

TIMOTHY CARRODUS

When Timothy Carrodus began investigating the World Bank’s $2bn loan to the Philippine government, the “scale of corruption” left the biggest impression on him.

But before he hit the global stage, he was a Victorian Police Officer for more than 18 years, rising to the rank of detective Inspector and working in the fraud squad.

Mr Carrodus said the experience was “invaluable”, particularly his time at the Detective Training School and Advanced Detective Training School.

He moved to private investigations in 1988 and has worked in the field ever since, taking on roles at a number of high-profile organisations including Myer, the World Food Programme, the United Nations and the World Bank.

It was during his time as the latter’s Senior Inspection Officer that he worked on what he said was his most memorable case.

“My most significant investigation was a $2bn loan from the World Bank to the Philippines Government that involved high level collusion with the tendering processes between politicians, government officials and contractors,” he said.

“The collusion was proved and the matter was referred to the Philippines government for a criminal investigation, but no definitive action was ever taken.

“The World Bank initiated their own sanctions procedure that resulted in several multinational construction companies being sanctioned (barred) from tendering for World Bank contracts.”

But he told the Herald Sun more work is needed.

“One person I interviewed in the Philippines stated, ‘ … it’s an open secret …’ and he was right,” he said.

“The corruption was at all levels and it continues today, very highly organised and condoned, but interestingly there is an appearance of legitimacy with no real substance.

“For example, I had a lengthy conversation with some genuine and decent people in Manila who wanted the situation to change, and the government gave this impression also.

“But there was no real and tangible action..”

Mr Carrodus’ work has taken him to a number of countries, and he spent a year based in the Democratic Republic of Congo as a Chief Resident Investigator during his time with the United Nations.

“My responsibility was to investigate any matters related to misconduct with the UN Peace-Keepers and UN civilian staff.

“Most matters related to sexual exploitation and abuse.”

He also spent time in Rome, after he was recruited to help establish a new office of Inspection and Investigation for the World Food Programme.

He said the work was “worldwide in all continents”.

“My investigations uncovered malfeasance, fraud and corruption in several countries that previously was undetected.

“Several very senior officials were dismissed for fraud, and corruption.”

Mr Carrodus is now based in Melbourne, where he works as a private agent for various clients, tackling jobs including insurance and workplace misconduct.

DEAN NEWLAN

When Dean Newlan left Victoria Police after 10 years – including four working in the fraud squad – forensic accounting “wasn’t even a term that was used”.

Now he’s a senior consultant at the accounting firm McGrathNicol and prior to that helped set up the forensic team at KPMG.

He has worked on famous cases including the Clive Peters case, where an accountant stole more than $19 million from the company.

He said his time in the fraud squad and finance degree sparked his interest in investigating white collar crime, a speciality he brought over to the private sector.

“I went to a consultancy role with KPMG and that kind of morphed into forensic accounting, at the time when forensic accounting wasn’t even thought about,” he said.

His former colleague, Wayne Gladman, described him as an industry pioneer.

“We were in the fraud squad together back in the late 80s,” he said.

“He was one of the forerunners in Australia really, taking the investigations to the accounting field.”

Mr Newlan’s specialty is financial wrongdoing, whether that’s embezzlement, fraud or cybercrime, and he said cases can last anywhere from a month or two at a minimum, to three years.

“One of the things we need to do in a lot of cases is to follow the money,” he said.

“It’s a fund tracing exercise essentially, which means you’d be combing through bank accounts.

“I had one where we had somebody who had stolen in excess of $10m and she had 60 bank accounts.

“So we had to trace all the money through those 60 bank accounts into various properties that she’d purchased and find out where those properties were, who owned them.

“Some of the properties had tenants in them so there was money coming back in through rental.”

He’s referring to the Clive Peters case, which he said had a “devastating impact on the company”.

“That was a tragic case in terms of the impact on shareholders, the impact on the employees and the impact on the perpetrator herself,” he said.

“The company came down because of it.”

Mr Newlan said he is keen to understand why people commit white collar crime, as opposed to just investigating the how, and that gambling is “pretty close to the number one motivator”.

“What I’m really interested in is the psychology,” he said.

“Gambling is a very common motivator for people who steal from their from their boss.

“In my 30 years of experience, I’m not saying gambling is the majority of cases, but certainly right up there.”

Financial hardship and being unable to afford a lifestyle one had become accustomed to are other common motivators, he said.

“Everybody is capable of stealing,” he said.

“If the right situation arises in their life, you don’t know what you’re going to do.”

He said in some cases, fraud can remain undetected for a long time, or even forever.

“There are victims who don’t even know they’ve been a victim,” he said.

“We know that there must be a lot of fraud that’s never detected because we’ve seen so many that have gone on for so long.”

He cited one case where a financial services worker who had a close relationship with his clients stole more than $6m from them over 16 years.

But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing that can be done.

He said many people didn’t realise how powerful the civil court system can be when chasing stolen money compared to police action, which he says can take years.

“If you take civil action … then you can freeze the money that is still in that account.

“I had one case where we took Supreme Court action within 48 hours and believe it or not the money was still in the account.

“So we put a foot on that $2m, which had been removed from our client.”

He said they can even apply to the Supreme Court for a search order, which allows a solicitor to conduct a private search.

“People think only the police can search your house but in effect you can get a civil search order.

“You have to have a fairly solid case … and the court, if it thinks it is appropriate to do so, will issue that order.

WAYNE GLADMAN

Like a few other well-known Melbourne investigators, Wayne Gladman learnt his craft in Victoria Police’s fraud squad.

He said he worked there for about 10 years, rising to the rank of sergeant, before he left for the private sector.

He’s worked with a variety of companies, from buy-now pay-later start-ups to major banks, where he oversaw card fraud investigations.

His risk management and prevention company Fraud Risk Solutions even spent some time advising car dealerships after a string of frauds.

But since the pandemic, he’s worked with the Health Department on their Covid response.

He said “it’s been a variety of shoots over the years”.

He told the Herald Sun people not only underestimate how common fraud is, but also the severity of the crime.

“People sometimes think some fraud is a victimless crime, particularly when you’re frauding the government or taking advantage of banking institutions,” he said.

“They don’t think of that the same as if someone robbed a little old lady down the street.”

He said anyone could be a victim and anyone could be a perpetrator, particularly in the digital age.

“As the electronic age is upon us, it’s easier for people to commit fraud,” he said.

“The phishing scams where you send out details of people and hopefully, someone will respond and give you their credit card details or rather bank details with their, their password.”

But one of the more notable cases he worked on didn’t rely on any savvy digital malware.

Instead it was an elderly lady who worked on accounts for Meals on Wheels and sometimes helped herself to some of the funds.

Altering records to hide her theft, she carried on unnoticed for several years before Mr Gladman was called in to investigate.

He said police would later determine her motivation was gambling – a common fraud motive – but even she was shocked by the amount of money – $150,000 – she’d funnelled away.

“When we worked out what her modus operandi was, we went back to the office, got all their records for the last four years worked out, and just by the accounting of what was received versus what was banked we could work out how much she’d stolen,” he said.

“I eventually rang her up and she was a bit unbelieving of the amount that we’d actually found.

“It’s a common sign that people don’t realise what they’ve stolen, how much they’ve stolen, they tend to put it in the back of their mind.”

Mr Gladman is also well known in the industry for launching the Australian Institute of Private Investigators with two of his colleagues.

He said they wanted the institute to be more than a networking body, and promote the standards of the industry.

“The principles of the organisation were really to enhance the reputation of the investigator because at that point, an investigator was seen as someone who went through your garbage, looked through your keyhole,” he said.

“We actually called ourselves the Institute of Professional Investigators and tried to ensure the professionalism of the institution.”

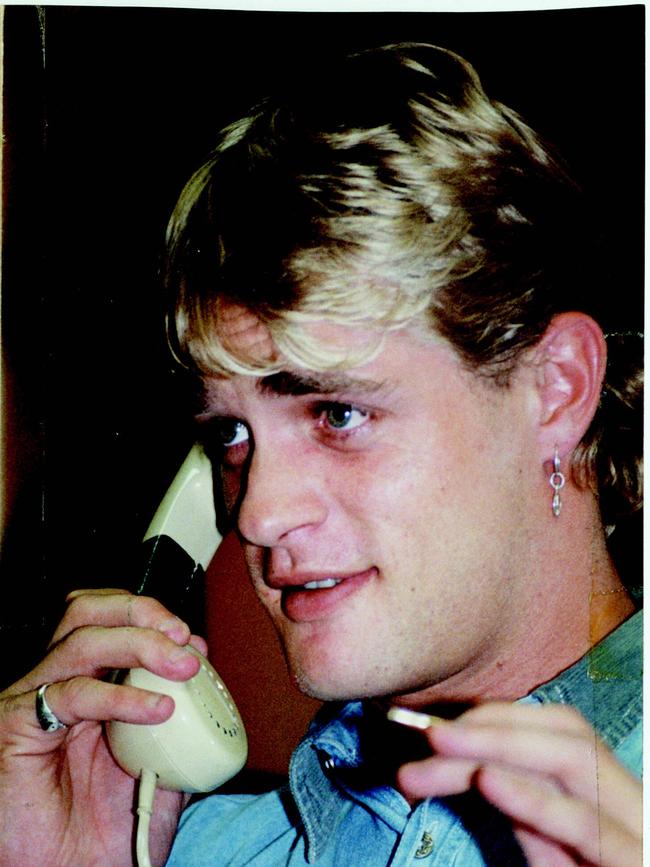

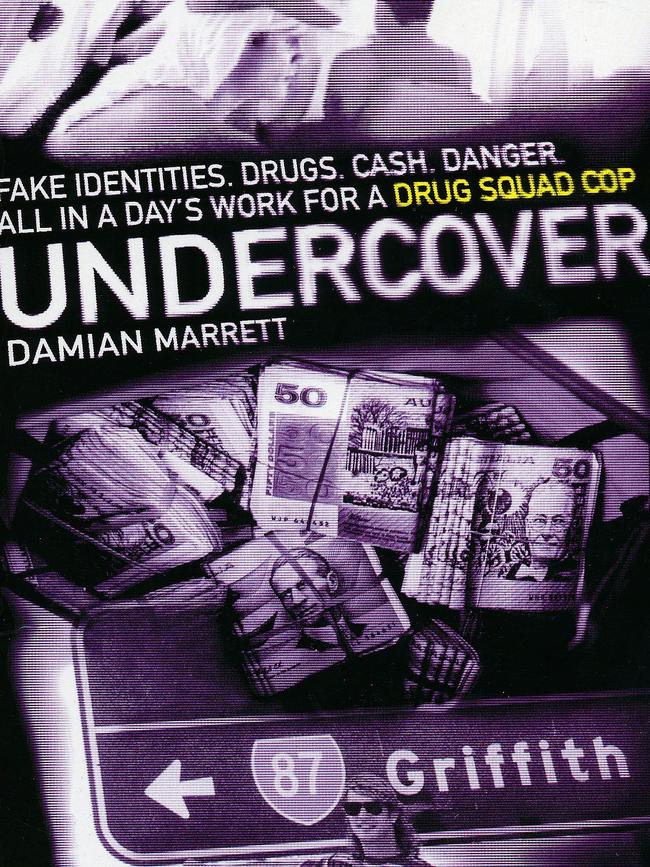

DAMIAN MARRETT

Damian Marrett is arguably best known for his undercover work, having published three books on his experience as an undercover officer during his time at Victoria Police.

He told the Herald Sun he worked across a wide variety of investigations during his “extended tenure as an undercover operative”.

“Undercover work is very much about thinking outside the box,” he said.

“After working on and mixing with drug dealings, gun dealers, paedophiles, workplace thefts, extortion, organised crime and the varying personalities and psychology of the hundreds of people I interacted with, being able to predict or at least consider different persons methods of hiding deception can be invaluable.”

The former detective said he no longer did undercover work himself, and now makes a living with his business Marrett Investigations Australia, which takes on a wide range of cases.

“I personally don’t work undercover on cases myself anymore,” he said.

“A few books, media and a website doesn’t make that too realistic.

“I combine the conventional and contemporary investigational techniques.

“The majority of my services are online based, such as dating scams, person identification, background and due diligence, child custody cases.”

He specialises in a variety of areas but favours historical locates, which involve tracking down individuals for a wide range of clients from biological parents and children and lost relatives to old school friends and class action witnesses from the sixties and seventies.

“These locates involve online investigations, archives, library archives and so forth,” he said.

“Obviously they’re extremely fulfilling investigations, such as reuniting family etc.”

While he said his experience in the police force was invaluable, the former cop believes in some ways private investigators have to be “more multiskilled and diverse than current police investigators”.

“Without police databases and specialised police units at their disposal, finding answers relies heavily on both conventional and contemporary investigation techniques, such as Open Source Intelligence Techniques (OSINT) and cyber techniques,” he said.

“As much as PIs would love to push a couple of buttons on police databases to identify or locate subjects, in many ways digging up information from numerous sources and techniques offer up a far greater amount of intelligence.”

But the job isn’t all fun and games.

He said the role can also attract people who need mental health help, as opposed to an investigator’s service.

“The most challenging jobs are the clients that suffer mental illness and especially paranoia,” he said.

“It is not about taking advantage of these clients and it is a hard balancing act in reassuring them ‘there are no bugs in your house’.”

He said the job title can also attract misconceptions about the lengths people will go to for answers.

“Hollywood and to some extent rogue PI’s have left the public with an image of PI’s with one foot in the criminal underground,” he said.

“Sorry but those days are long gone in today’s world.

“Investigation licences and business licences are extremely well-vetted nowadays and on the flip side easily withdrawn at the first hint of impropriety.”

Mr Marrett takes on cold cases pro bono and at the moment is focusing on the disappearance of “Australia’s first celebrity chef”, Willi Koeppen, who vanished more than forty years ago.

He was last seen in the early hours of February 29, 1976 at the Cuckoo restaurant.

Mr Marrett, who is working with Koeppen’s family, told Herald Sun journalist Andrew Rule the case was badly investigated.

He believes there are people who know what happened and is keen to speak to anyone with information.