Police on beat in the gun, writes Andrew Rule

NO one will be haunted more by images of an upturned pram and dead children in the wake of Bourke St than police, writes Andrew Rule. But should we question our confidence in Victoria’s force?

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Police command ordered officers against rushing to intercept suspect cars

- Police requests to intercept car rejected

- Flood of support for CBD victims

Greg Davies: Bail is sometimes a life and death decision

Justin Quill: Changes overdue on bail laws

EVERYONE in Victoria is an expert on two things, says former Police Association boss Greg Davies: “AFL football and policing.”

He is only half joking. Last Friday’s terrible events have hardened the views of many Victorians already increasingly uneasy over the perception of a rising tide of crime, much of it drug-fuelled and senselessly violent.

It’s a tricky debate. Police on the street are being overstretched by the competing demands of keeping the lid on crime and dodging the career-ending threat of one reflex decision gone wrong.

Told by police command that “Time is on your side”, street police have to weigh up the possible long-term consequences of giving in to their instinct to tackle offenders head-on.

Every uniformed officer has to wear a belt that holds handcuffs, capsicum spray, a baton and a heavy pistol. But added to that is an invisible book of rules, memos and instructions that weighs heavily, filling the mind with confusing and perhaps contradictory messages.

But one message is clear: a split-second decision to take the fight to the bad guys could injure or kill you or others, and not necessarily the offender.

No wonder junior police are reluctant to buck the gentle approach which, some say, led to a violent and unpredictable man being trailed for hours last Friday before many innocent people were run down.

As angry Victorians wonder whether our police or our legal system — or both — should be blamed for the Bourke St horror story, it’s tempting to talk up the “good old days”.

The fact is, old-time cops were not always right and modern police are not always wrong. But it’s easy to select examples to make it look that way — such as when, in 1983, prison escapee and serial armed robber Ian “Rabbit” Steele, on the run with a hostage, was spotted in a car at the north end of Swanston St.

Two well-known detectives, Paul Mullett and Jim Venn, cut off Steele’s car in their police vehicle. When Steele produced a sawn-off shotgun, Venn shot him in the head.

Unluckily, perhaps, the thick automotive glass deflected the bullet enough that Steele was not killed. He would later escape again to flee overseas, where he was eventually jailed for life for strangling a woman.

The policemen’s bold decision meant the public (and the hostage) was safe from Steele. Mullett and Venn received valour awards.

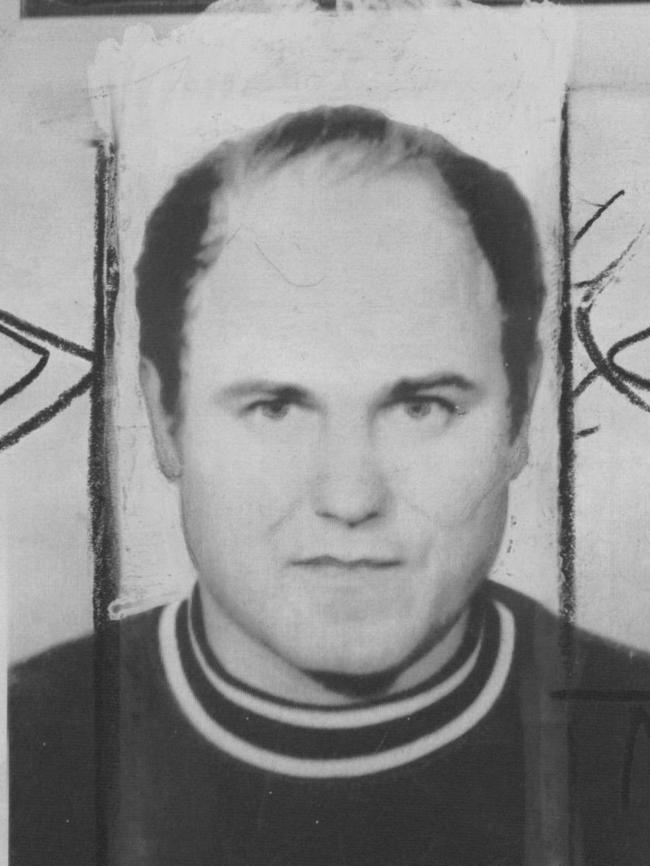

Two years later, two detectives shot and killed another fugitive gunman, Pavel “Mad Max” Marinof.

He had wounded them with a handgun when they intercepted his panel van on the Hume Highway, north of Melbourne.

Marinof, a Bulgarian army deserter, gun nut and crack shot, had been hiding for eight months after one terrifying night in which he shot four police officers, putting one in a wheelchair for life.

It was the wounding of six police by “Mad Max” that triggered a wave of police shootings, which would eventually create a backlash from citizens looking back nostalgically to an era when police hardly carried guns, let alone used them.

Victorian police had become so notoriously “trigger-happy” that one visiting NSW detective who crossed the Murray for a joint operation wisecracked: “We won’t take any bribes if you don’t shoot anyone.”

But it was no joke to senior police or to their political masters, who were under increasing pressure from the public and the media not to spray bullets around like cowboy cops in Al Capone’s Chicago.

The official response was Operation Beacon, an urgent program to train every Victorian police officer to do almost anything except shoot first.

The spirit of Operation Beacon is alive and well.

Its “turn the other cheek” approach underpins the memo written by a senior officer last year warning officers against ramming cars — or shooting suspects — to deal with offenders who had begun deliberately ramming police cars or driving at officers who were on foot.

Not only did this trend put police officers “in very real danger” but it “resulted in damage to police vehicles,” the memo states.

To be fair, its writer also made the sound point that law enforcement experience worldwide had overwhelmingly shown that “If you shoot at a moving vehicle with the intention of stopping it, you won’t.”

Then there’s the warning that as soon as you shoot a driver, his vehicle is then out of control.

And there’s a list of safety tips that mostly involve staying in the police car with the seat belt on and avoiding high-speed pursuits.

It is impossible to prove a negative, so we will never know how many lives and injuries — and police car panels — this policy of caution has saved.

Against that, of course, is last Friday’s toll of dead and injured.

No one will be haunted more by images of an upturned pram and dead children than the people we pay to do our dirty and dangerous work.