Disbarred lawyer could unlock mystery of Mark Jansen’s disappearance

In the months before he vanished, Mark Jansen was a degenerate gambler betting black money for a “syndicate” run by a disbarred lawyer. His sisters are still trying to piece together the dangerous maze his life had become.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Mark Marinus Jansen was a sixth-generation fishmonger, son of a Dutch migrant who arrived in the 1950s and continued the family trade in fish markets around Melbourne.

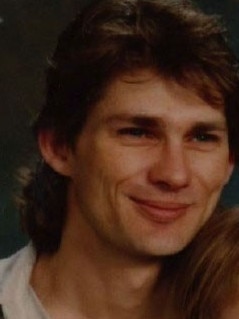

Young “Jack” Jansen married Dorothy and built a life. Mark, born in 1963, was the oldest of their four children. He was admired and adored by three sisters, Shasha, Paula and Starry.

They lived in Croydon, then on a bush block at Wesburn near Warburton before moving to inner-suburban Kensington close to the busiest markets.

Mark took up the family trade as a teenager and worked hard. At 21 he was running his own business, had bought a house, married and was starting a family.

He was tall, blue-eyed and square jawed, a dashing figure to his sisters and their friends. He dressed down in T-shirts, his favourite leather jacket and jeans. To his sisters, the more casual he looked, the more stylish he seemed.

Once, a casting agent stopped him in Chapel St and asked him to be in a commercial with surf star Grant Kenny. After being flown to the location in Queensland, Jansen decided film wasn’t his thing.

“He was such a guy’s guy,” says little sister Starry about her brother’s offhand rejection of that invitation to a very different world.

Jansen stuck to his trade. He was a fish market man, one of a robust breed used to early mornings, razor-sharp filleting knives and the daily gamble of buying and selling.

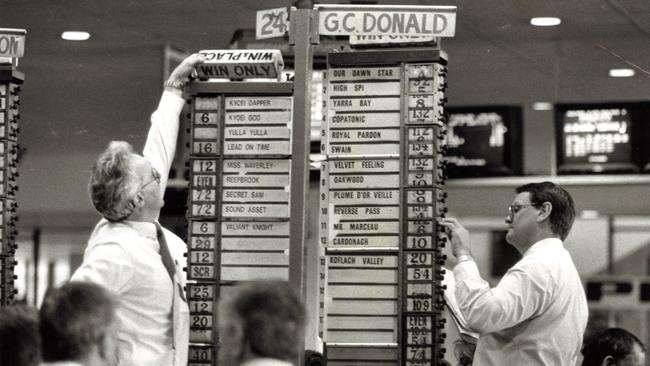

The trouble was that the gambling side of his nature took over more and more. His family knew he gambled but didn’t realise how much until he took Starry to Moonee Valley harness races in the early 1990s.

Starry was amazed to see Mark handling huge bets for what she calls a “syndicate”, apparently run by a dark-haired man she was told was a disbarred lawyer.

The name the disgraced lawyer used was almost certainly bogus. No bookmakers, racing writers or stewards who worked the trots in that era heard of it then or later.

Mark shocked his little sister that night by handing her $10,000 in cash and asking her to bet on a particular horse for him.

The horse didn’t win. Starry was staggered that Mark didn’t seem to care about the loss of a sum equal to several months’ pay. He was deep in a scene where huge money changed hands routinely.

Starry was puzzled. Was her brother betting on his own account as well as running bets for a crew that wagered mountains of cash?

Either way, it was dangerous.

This was an era when bent solicitors “minded” milk crates full of cash in their offices so their clients could collect it to take to the races or the new Crown casino to “launder”.

One 1980s jockey recalls waiting in the luxury car of a notorious underworld figure known as “the Black Diamond” as he fetched crates full of $100 notes from the city office of a lawyer dubbed “the Spider”.

Before the rising drug dealer Tony Mokbel and his “tracksuit gang” flooded betting rings with black cash, the Black Diamond and another race-fixing punter, a Chinatown identity we will call Mr Wrong, did “business” with a string of jockeys and trotting drivers, notably the flawed champion Vinnie Knight.

People throwing wads of black money at bookmakers and casino croupiers were representing criminals, usually drug dealers, prepared to lose a big percentage to wash dirty cash.

Anyone who used drugs and gambled heavily ran a risk of looking like “loose cannons” likely to reveal crime connections.

Over time, gamblers lose. Desperate gamblers run up debts they can’t repay then resort to gangster loan sharks who demand extortionate interest of up to 50 per cent per week.

If the punter doesn’t pay on time, he risks a bashing. Miss another deadline and he’s gambling his life.

“Sometimes the loan sharks have to make a point,” says one of Mokbel’s former pet jockeys. “So they bury you.”

One Melbourne Cup-winning jockey reportedly fled Australia in fear after borrowing big money from a heavy at Crown. The star jockey Rod Griffiths also had a narrow escape from a similar dilemma.

In the months before his disappearance, Mark Jansen had become a degenerate gambler, his life off the rails. He had separated from his wife, mother of his two young daughters, and stayed in a caravan in Dandenong that he shared with a married man who was his partner in his fresh fish business in Pultney St.

The partner was Robert Streater, who “fronted” the business because Jansen was officially bankrupt.

The business was overshadowed by Jansen’s gambling. The distressed Streater would call Jansen’s sisters to complain that Mark emptied the shop till to bet with and was often absent.

It had to end badly. But exactly how it ended is unknown.

On November 12, 1994, police believe, Jansen left the shop around 5pm. What happened next is vague and patchy.

At one point, says Starry, it was claimed that Jansen had gone to the nearby New Hotel after work. But when Starry later went to the hotel with a picture of her brother, none of the patrons or bar staff recognised him. She thinks he never went to the hotel.

Starry also doesn’t believe the vague story that her brother got a lift to meet someone in Broadmeadows.

Or the variation that Jansen got into a “yellow Gemini” with three other people, supposedly heading to South Australia for the Grand Prix.

Apart from anything else, Mark had agreed to meet his wife Nola and two much-loved daughters, Lichelle and Mandy, for a family dinner that night, and he didn’t appear.

Another reason Starry doesn’t believe Mark left Dandenong voluntarily is that when the caravan was searched, there was blood in it — and her brother’s doona was gone. Whereas the brown leather jacket he always wore, regardless of the weather, was still there.

While it’s quite possible the blood was from a cut finger, as fishmongers often cut themselves, the missing doona and unworn coat still seem sinister to the Jansens.

Starry believes the doona was used to move her brother’s body. If Mark’s partner Streater knew or suspected more than he told police, he wasn’t saying.

Starry doubts that Streater had the nerve to kill her brother, but that he could well be terrified of those who did.

Streater, then 31, had no history of violence at that time. But after he and his wife moved to a former schoolhouse at Caldermeade, near Lang Lang, he ran off the rails.

Robert Andrew Streater, born in 1963, was charged with rape in 2006, convicted in 2008 and sentenced to six years and six months jail with a minimum of three. A charge of threatening to destroy property was dropped.

Meanwhile, the Jansen family lived under the shadow of Mark’s presumed murder. They hoped he’d fled interstate but knew he was almost certainly dead.

In early 2007, Mark’s father Jack died, broken-hearted. His shattered widow Dorothy gave the police forensics division a DNA sample against the tiny chance that her boy’s remains were ever found.

The odds against that were huge and getting longer every day … 7061 of them, as it turned out.

MIRACLES HAPPEN

At 9.30am on March 13, 2014, two weeks after a bushfire, excavator driver Andrew Keath was pushing up burnt and fallen trees in a gully beside the Morris Track, in remote bush north of the Marysville to Woods Point Rd.

Keath was using a 20-tonne machine that could crush or move almost anything. By chance, he happened to notice something white rolling out of a heap of logs he was pushing.

It looked a little like a faded old fibreglass “hard hat” of the sort used before yellow plastic helmets came in. But it was too small.

He got off the machine to have a look. It was a skull, the bottom jaw missing. He could see dental fillings in the remaining teeth.

He called his boss. Local police eventually arrived, grumbling that it wouldn’t be a skull. Then they saw it.

Not long after, homicide detectives hired Keath to bring a smaller machine to search properly. They told him the skull had already been identified through DNA but no one had been told yet.

Police needed certain things in place before breaking the news in the dead man’s circles.

The coroner and a forensic pathologist with the detectives checked for bones or other clues. All they found, as Keath recalls it, was one partial femur.

Keath never forgot what the expert said: that the femur had been cut.

He guessed then that the body parts had been scattered, thrown into the bush from the track.

THE BUTCHERS

What sort of killer cuts up bodies? One, maybe, who routinely uses knives, cleavers and saws. There are people who deal in blood and bone besides fishmongers: butchers and slaughtermen, for instance.

Working around markets, Mark Jansen knew plenty of butchers. His sisters recall one lot calling Mark over for “morning tea” daily. He would come back wired and fired up, clearly from taking speed with the butchers.

Starry doesn’t know who introduced Mark to the debarred lawyer who recruited him to launder money at the races, but wonders about the butchers’ amphetamines connections.

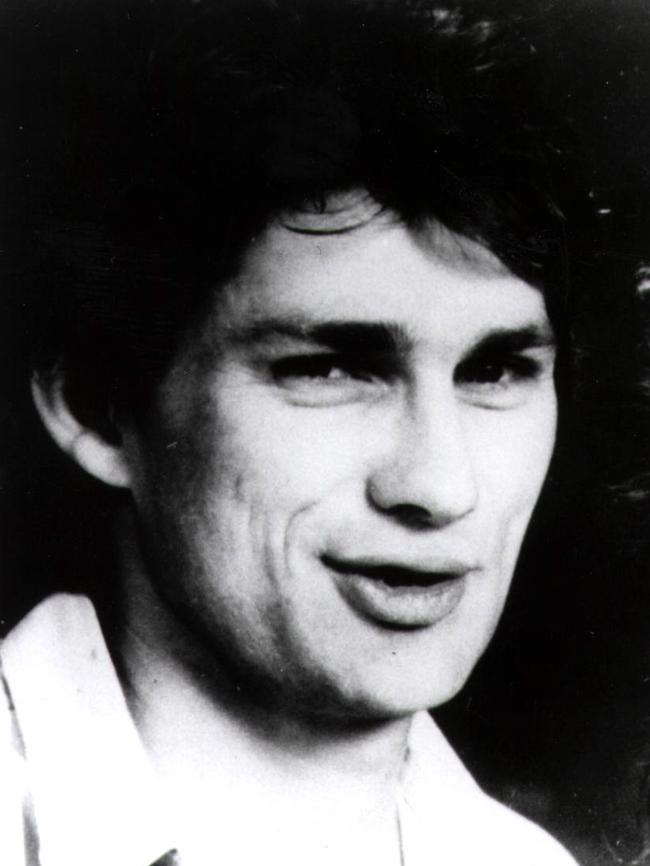

By 2014, only a few older police and reporters clearly recalled the disturbing case of Philip Peters, assumed name of a disgraced lawyer named Peter Philip Raftopoulos, born in 1945.

Peters stole people’s identities to open false bank accounts to run scams, among other crimes. Apart from theft and fraud, he was known as “Mr Laundry” because he washed dirty cash for drug dealers.

Peters fell out with a criminal named Peter Kyprianou, alias Kypri, over a $200,000 insurance scam. He plotted to have Kypri abducted and killed in a farm cellar by a butcher called “John”.

The butcher didn’t like Peters’ idea of torturing Kypri then cutting him up for easy disposal, so he went to the police. They charged Peters with conspiracy to murder, although he did a deal and was jailed for lesser offences in 1994.

But Peters could organise crimes from prison. It’s suspected that he planned the murder of Kypri’s wife, Carmel, to punish him. The hit was carried out in November 1997 — but the paid killers shot the wrong woman, Jane Thurgood-Dove.

The fact is that Philip “Mr Laundry” Peters was a psychopath who fell out with people, carried grudges and dreamed of having enemies killed and cut up.

Which poses a question: was “Mr Laundry” the debarred lawyer who used Mark Jansen to bet black money at the races?

After 28 years, it’s probably worth a look. Peters was last known to be hiding in the far west of Victoria with a woman and a young child.

Victoria Police this week stated: “Missing Persons Squad detectives continue to investigate the disappearance and subsequent death of Mark Jansen in 1994. The case remains open and any new information provided to police will be thoroughly examined.

Detectives urge anyone with information to contact Crimestoppers on 1800 333 000 or submit a confidential crime report at www.crimestoppers.com.au”