Andrew Rule: Does tragic tale of Adele Bailey start in St Kilda polcie station?

Could the tragic tale of a sex worker found down a mineshaft begin in an act of brutality at a police station in the sleaziest sex-and-drugs scene between King’s Cross and Antarctica?

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A long time before being killed and thrown down a Bonnie Doon mineshaft, Paul Bailey felt like a girl in a boy’s body.

That was back in New Zealand, where Bailey’s Pitcairn islander forebears — descendants of Bounty mutineers and Tahitian women — had settled after leaving the nightmarish island.

Paul Bailey escaped one ordeal only to find another. As Adele Bailey, she worked as a prostitute in Melbourne in the mid-1970s to pay for a sex change operation in Egpyt.

But the streets were dangerous for the harmless hooker at a time when police were often brutally intolerant. When Adele went missing in late 1978, no one but a few fellow sex workers and her distant family knew or cared.

Adele’s name was unknown to the public until 1995, when her skeleton, silicone breast implants and a few rotted feminine items were found deep in a remote shaft in the hills behind Bonnie Doon.

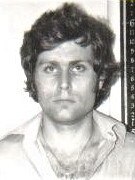

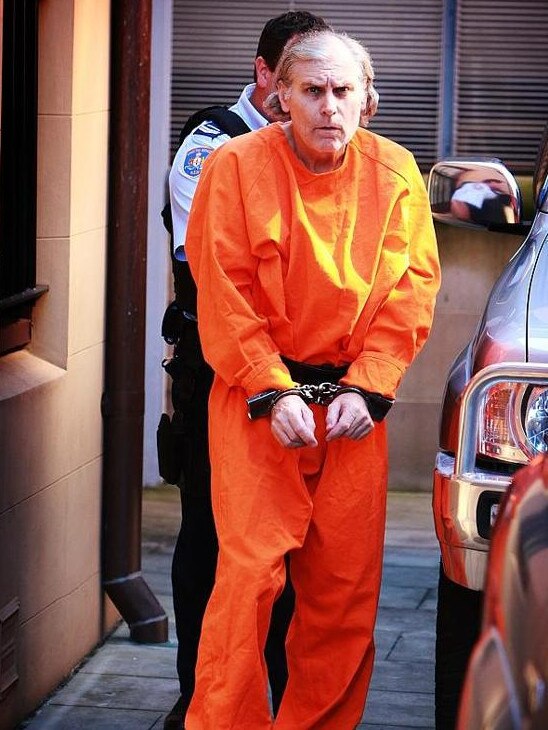

Now poor Adele is back in the news, this time linked to Bandali Debs, the psychopathic killer who as a disturbed young man hung out with transgender sex workers in the old St Kilda red light district.

Strange and violent men, some of them police, exploited vulnerable sex workers like Bailey, and Debs was both strange and violent.

Known in the mid-1970s as “Joe”, the spooky chameleon who’d fled from police heat in Sydney carried a handgun and liked to frighten people.

The significance of Bandali Debs’ link with Adele Bailey is that one of her former prostitute friends gave police his name in 1995 after Adele’s bones were found in the abandoned mine on a ridge behind the old Tanner farm.

The fact that police were told about Debs and his guns three years before he killed policemen Rod Miller and Gary Silk is intriguing. But it has no bearing on who killed Adele Bailey.

What’s intriguing is that investigators missed the tip-off, failing to put Debs’ name on a list of known or potential armed robbers capable of murdering the two policemen in Moorabbin in 1998.

There is absolutely no evidence Debs had anything to do with killing or disposing of Adele Bailey, given that the hidden spot where her remains were found was familiar only to relatively few people with local knowledge.

Besides, Debs shot people — usually in the head — and Bailey was not shot. She almost certainly died violently at the hands of a man but it’s unlikely she was deliberately murdered.

The coincidence that Debs was one of many lowlife men who paid, cajoled or intimidated Adele Bailey and other streetwalkers for sex does not make him a real suspect for her murder.

Because such coincidences can obscure sinister truths.

The truth about Adele Bailey’s fate, say two consistent sources 27 years apart, is that it was much closer to home for the police investigating it.

The background to Bailey’s death and, six years later, the shooting of Bonnie Doon farmer’s wife Jennifer Tanner, were open secrets in the police force for a generation.

In 1996, a twitchy detective murmured a succinct version of what he said “might” have happened, whispering so he could not be tape-recorded in a city bar unlikely to be frequented by other police.

This week I was again told a more detailed version of the same story by an angry former policeman who called unprompted to volunteer details he and others have known since Adele Bailey went missing in mid-September, 1978.

Some background. In the 1970s, St Kilda police were cowboys, running hot at the notorious station in the hardened artery of the sleaziest sex-and-drugs scene between King’s Cross and Antarctica.

There were “throwaway” guns stashed in the ceiling, blood on the floor and cash and drugs in thieves’ pockets and hookers’ handbags. Brothels run by crooks like Geoff Lamb were protected by bent cops like Paul Higgins who burned out or bombed competitors and reputedly dropped the odd body in the bay.

Even respected police like Gary Silk, later murdered by Debs, had fun times in the station with the endless procession of repeat offenders. One interrogation trick was what Silk’s crew called “the jet ski”, which involved standing on an arrested person’s back, holding their handcuffed arms high behind them as if steering.

Another well-known cop would strip suspected drug dealers naked and throw them into the bay at gunpoint — until the night one started drowning and had to be rescued by another policeman who, bizarrely, received a bravery commendation for it.

A darker version of that sort of behaviour was called, in cop shorthand, “doing the chicken”. It meant exerting pressure on a victim’s neck so that it blocked the carotid artery long enough to mimic a stroke, with the victim going into involuntary spasms, arms and legs jerking.

Upstanding police would never apply “the chicken” unless it was absolutely necessary. To extract a confession, say, or to subdue a dangerous suspect. But not all contemporary cops were scrupulous and some were sadistic.

One of them, according to two sources, applied the carotid hold to Adele Bailey in or near the old St Kilda police station — but, instead of lapsing into unconsciousness, she died.

Her sudden death left a number of police with an urgent problem: a body, the result of casual brutality and suspicious circumstances that would anger friends and relatives and attract unwelcome media attention if revealed.

But what if the body simply vanished before any outsiders knew? The disappearance could then be easily written off as just another runaway transient prostitute, gone interstate to start over, the way Bailey had arrived from New Zealand a few years earlier to earn the cash to pay for a sex change operation in Cairo.

The cop network kicked into gear. Someone called in a police “groupie” named Chris, a volatile Vietnam veteran who bought and sold guns and ran a security business that employed off-duty cops as bouncers.

Chris lent the conspirators a dark-coloured panel van to spirit the body away. One of the crew knew exactly the right spot — one of the countless mine shafts that dot rural Victoria. Job done.

A former country recruit named Denis Tanner worked around St Kilda at the time. In fact, Tanner was the last police officer to arrest Bailey, whom he referred to as one of “the f---ots” who “looked after” him.

The only people who know who was with Adele Bailey when she died are either now dead or are not talking.

Bailey’s family in New Zealand were distraught but could get no answers from Melbourne police, then or later. They were too poor, too powerless and too far away to do anything.

The disappearance of the pretty boy who became a tough girl would have been forgotten by all but family and friends except for a chance find 17 years later.

On July 19, 1995, two young men exploring the old Jack of Clubs mine shaft in hills behind Bonnie Doon, found a skeleton later identified as Adele Bailey’s.

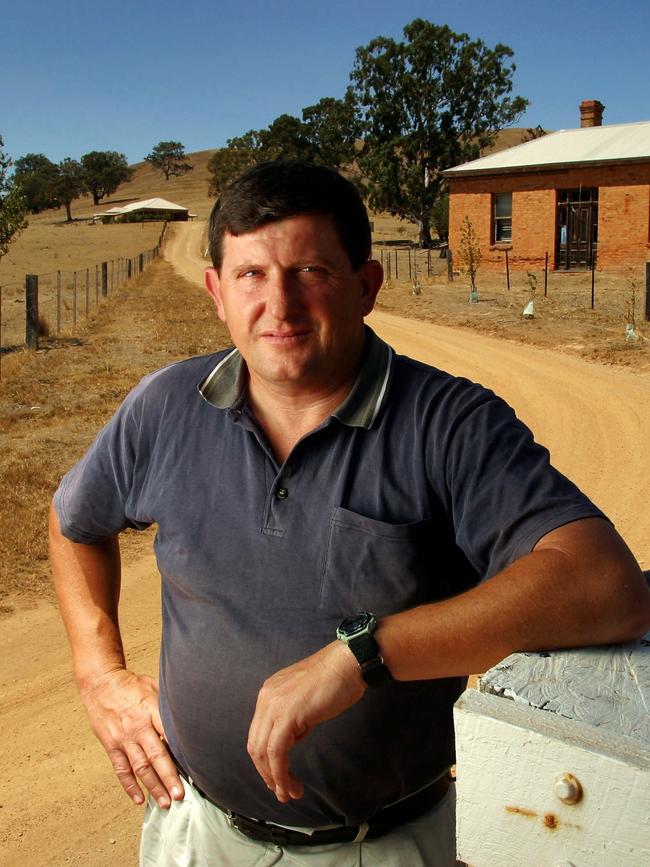

The short version of a long and eerie story is that it sparked an investigation that eventually led the state coroner to name Denis Tanner, a serving police sergeant, as the killer of his sister-in-law, Jennifer Tanner, at the family farmhouse down the valley from the mine, although the Coroner found there was insufficient evidence to lay charges against Tanner and he has always denied involvement.

Tanner and his mates had links with Bailey. He worked and lived around St Kilda in 1978, had arrested her there, frequented a South Yarra hotel where transgender people drank, and boasted of getting money from “f---ots”. As kids, he and his brothers had thrown rocks and dead sheep down the old mineshaft.

But none of that, nor other evidence heard over four days of inquest hearings into Bailey’s death in 1999, was ever going to incriminate Tanner — who denies he was involved in her death and has always protested his innocence — or anyone else.

Such as, for instance, his one time friend and housemate, former knockabout policeman Mark O’Loughlin, who went on to work for Crown Casino after marrying a wealthy bookmaker’s daughter and using her surname to hyphenate his own. O’Loughlin also denies any involvement in Bailey’s death.

The newly-named Price-O’Loughlin pulled a full house in the coroner’s court when the Bailey inquest was held in 1999. It was a sequel to the long-running Jennifer Tanner inquiry, held over the previous two years (after the first obscure inquest into the death, held in a Mansfield church hall in the 1980s, had been quashed).

Under cross-examination, the former Sgt O’Loughlin admitted changing his surname since his freewheeling days in the St Kilda crime cars, but didn’t admit much else.

He grudgingly acknowledged a friendship with Denis Tanner. Beyond that, it was hard going. But counsel assisting the coroner, the steely Jeremy Rapke, raised some interesting questions for him not to answer.

Rapke produced a list of insurance claims Price-O’Loughlin had made as a young policeman but had seemingly forgotten.

Such as the black opals stolen when he left them in his car in the St Kilda street where he once lived with Tanner. And other thefts he had trouble recalling.

He recalled buying a holiday unit at Bonnie Doon with two other policemen in 1978, but said he hadn’t attended any parties there with prostitutes or strippers, and kept little property there because he rarely used the place.

Which proves that maybe memories can play tricks, because Rapke produced an insurance claim listing (as stolen from the unit) four dozen bottles of beer, two bottles of whisky, a barbecue and other things used to entertain.

Price-O’Loughlin shrugged off suggestions that an insurance claim had been made for a boat named the Slick Chick — later found, mysteriously, on the bottom of Lake Eildon.

Like Adele Bailey’s bones, Slick Chick eventually surfaced. But, in each case, no one is saying who hid them.

Chris the panel van man can’t help. He was buried with military honours two years ago.