Hardmen of forgotten footy era delivered broken jaws and broken dreams

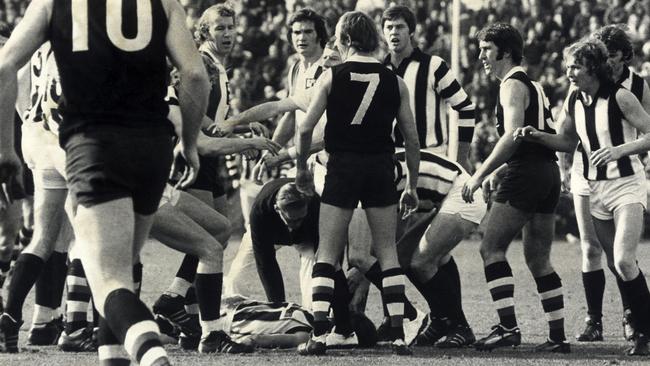

The VFL in the 70s was the aggro stepfather of the AFL, where rank amateurism and brutal professionalism combined in king hits that would get you jailed if they were thrown off-field.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They say if you remember the seventies, you weren’t there.

But older football followers were there — and remember it vividly. The VFL, aggro stepfather of the modern AFL, bristled with violence that’s no longer tolerated in the game.

Even so, not all the rough stuff was caught by the primitive TV coverage of a game in which rank amateurism and brutal professionalism were exactly that: rank and brutal, especially behind play.

On-field assaults put players in hospital with broken jaws, broken noses, broken ribs and broken dreams — and would have put others in jail if they’d swung the same king hits in the street.

As the song went, the 6.30 news was a horror movie, and that included sports bulletins.

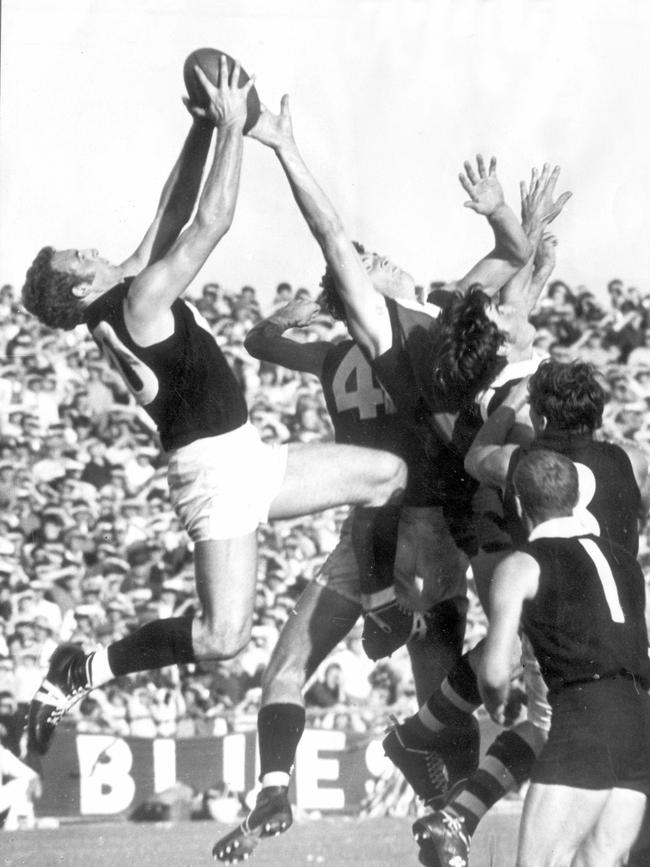

Try this. In round 14 of 1972, the sublimely talented ballplayer John Greening ran onto the Moorabbin ground for his 98th League game. At 21, he realistically thought he might play more than 300 games — something his coach Bob Rose thought fair enough.

Greening was a footballing freak. He’d been signed by the Magpies at 15 and played his first senior game at 17. Tim Watson meets James Hird with various Riolis and Abletts thrown in.

His meteoric rise ended viciously. He woke in hospital from a coma, doctors telling him he’d nearly died and would be lucky to recover from being paralysed down one side.

He’d been felled behind the play by St Kilda’s Jim O’Dea, who was lucky not to be charged with grievous bodily harm.

An eight-year-old watching that day prayed for Greening’s recovery all week. His name was Eddie McGuire.

Greening did play again — sort of. Two years later he made a comeback but could handle only a few games before retiring to try to forget the terrible wrong against him.

His devastated wife was dissuaded from taking legal action when St Kilda and Collingwood raised $50,000 in blood money, playing a fundraising game in which, bizarrely, O’Dea played.

That says more about 1970s football than any other single incident. But there were plenty of them.

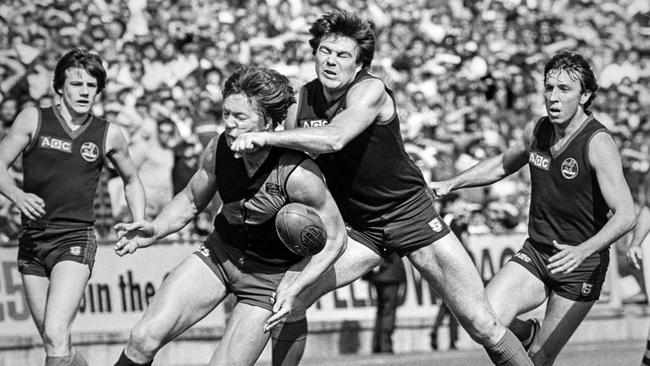

Football was war. Nearly every team had “enforcers” to intimidate opposition talent — and to protect their own ball players from opposition thugs. An arms race.

Most of those old-school hard men have slipped from legend into semi-anonymity, like retired heavyweight champs. Carl Ditterich and Ron Andrews come to mind but there are others. They know who they are.

Every club had them, except maybe the “handbaggers”, as the tough city clubs called Geelong for recruiting ball players to play open, skilful football as if they were playing sport rather than spilling blood at the Colloseum.

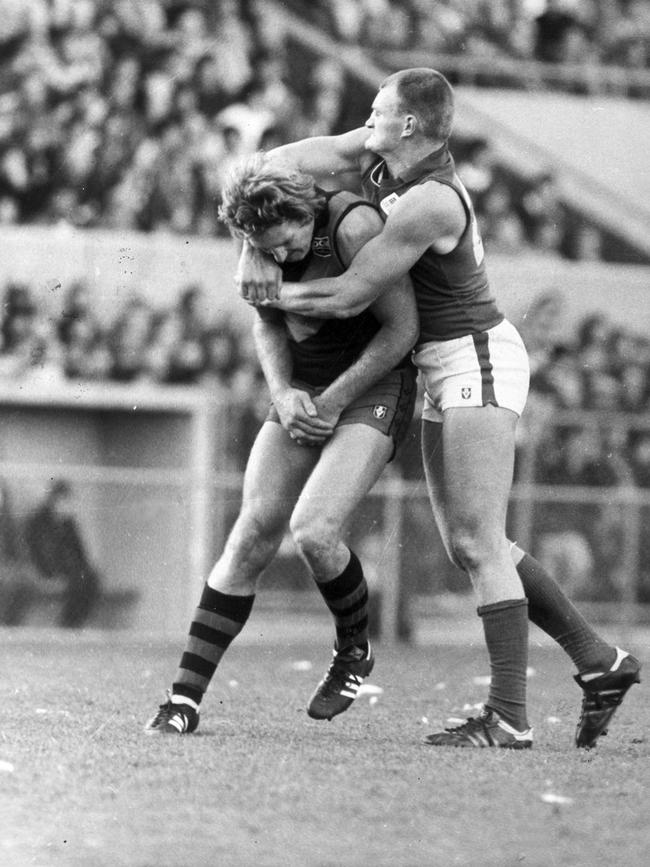

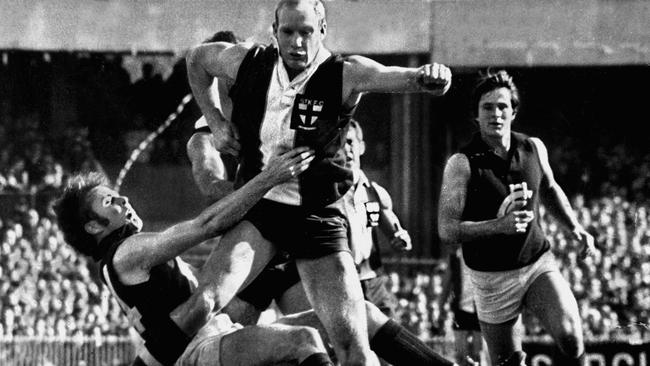

As gladiators go, “Big Carl” Ditterich had everything but the sword and spear to go with God-given talent and Nordic warrior looks. Caligula would have loved Carl. He had the size and colouring of a polar bear but wasn’t nearly as kindly.

Once the bear has killed and eaten a walrus, it will ease up until it gets hungry again. But Carl wasn’t so easily satisfied, especially in the later stages of his 17-season career. He terrorised lesser beasts on principle.

Even in his last game, when the sinful Saint had joined the Demons, he wounded half a dozen Collingwood players from sheer habit.

“Rotten Ronnie” Andrews seemed more amiable off the field than Killer Carl but was just as dangerous to the young, old, talented or those brave enough not to dodge him. Andrews drives a school bus these days, a long way from Windy Hill, Victoria Park and the MCG, and it’s a fair bet the kids don’t give him much lip.

Another hard man of the era, Stewie Gull, could now afford to buy the old South Melbourne ground just to park his cars, boats and horse floats. But the tycoon is not as proud of his property empire as he is of the fact he once poleaxed Ronnie Andrews at Windy Hill.

Make that twice. When Andrews gamely challenged him to “try it again”, Gull hit him again.

It was Gull that Carlton’s sneak puncher Wes Lofts ran away from after blindsiding some smaller Swans player the same way he’d once belted the only League footballer who wore glasses on the ground, Essendon’s gentlemanly forward Geoff Blethyn.

Even Lofts’ teammates never forgot his self-preservation instinct. He cut a dash in business and at parties but never quite lived down running from Gull.

The old South Melbourne followers called their team “the Bloods” and the fighting forward from Ballarat never let them down. They came to watch him fight at Festival Hall. Running away wasn’t for him.

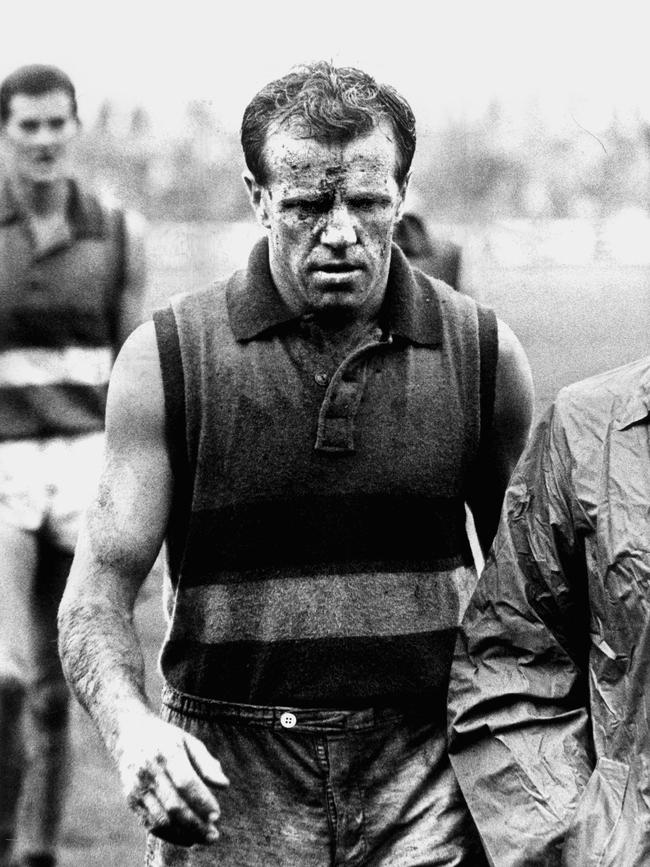

Tears flowed when “Mr Football”, Ted Whitten, succumbed to cancer in 1995. The sight of his wasted body in an open car at the MCG, punching the air and croaking his war cry one last time — “Stick it up ’em”— was one of sport’s most moving moments.

But, of course, this same hero had smashed 17-year-old Peter Hogan’s jaw in the boy’s first game for Richmond, the way that young Whitten’s own debut had been ruined by “Mopsy” Fraser in 1951.

That year, Victoria hanged a woman, Jean Lee. It was a very different time.

Most of the big-name hard men are long lost to elite football. Only a handful stayed around.

“Lethal” Leigh Matthews reinvented himself as a thinker in the game that has outlawed the unthinking mayhem he routinely committed in the Barney Rubble era with its single field umpire and stone age cameras.

Kevin Sheedy was a heavy thinker, too, even when he was just a heavy back pocket player. He and “Lethal” became super coaches who made a permanent mark on their sport.

But, as the bruisers of the 1970s enter their own 70s, perhaps only one of them is still exerting influence on a game barely recognisable as the one he played in that dark and deadly decade.

His name is Neil Balme. And, as a new biography by Anson Cameron makes clear, he’s not so much a reformed character as one who found his true vocation after hanging up his boots with the Tigers.

Balme quit playing when he was just 27, his knees a mess. But he never quit thinking about how to play football a better way — a tendency he’d shown from teenage days, exasperating old-time coaches like Ray “Slug” Jordon and Tommy Hafey, who preached the virtues of fitness and fierceness rather than tactical finesse.

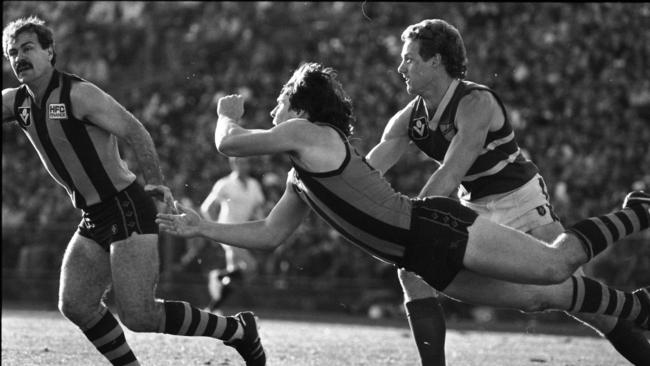

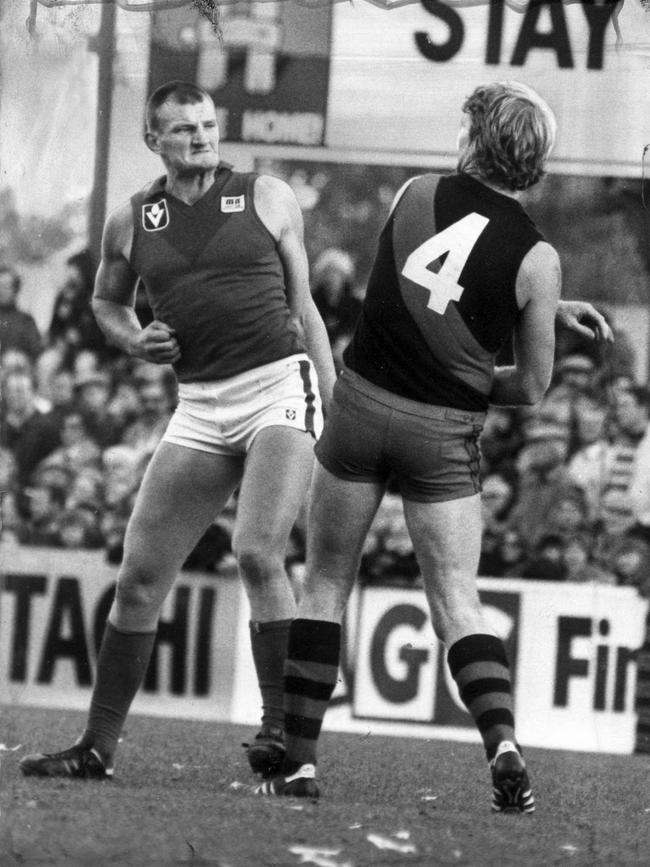

The perception is that Balme is a changed man. The man himself argues — gently and persuasively, with humour — he never really was the pitiless thug he seemed, the Tiger who spooked a generation of opposition players during his decade of living dangerously.

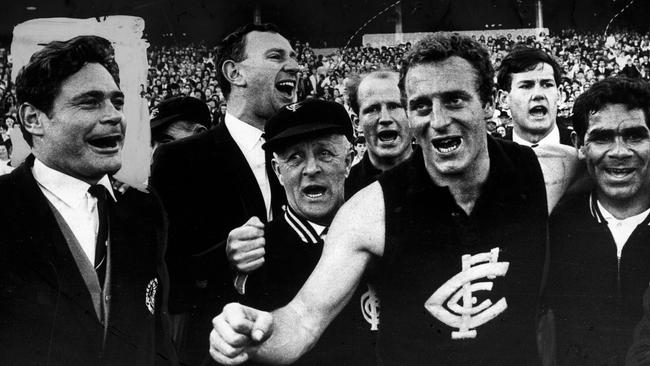

Balme was, or still is, hated by two generations of Carlton supporters because he concussed Geoff Southby, broke David McKay’s jaw and flattened Carlton’s own heavy, Vin Waite.

Mouthy Carlton players openly taunted Richmond’s gentle ruckman Michael Green, a law student. But when Balme took his turn in the ruck, an eerie silence fell over the centre square.

Not that Balme’s blues were limited to Carlton.

He was an equal opportunity enforcer, happy to dish the dirt without fear or favour, even to Ditterich and the crazy brave Don Scott.

As Carlton’s premiership ruckman Mike Fitzpatrick said years later, “Balmie was top of the food chain, don’t worry about that.”

But underneath the rugged exterior was the thoughtful student of the game who has turned into a football Buddha, dispensing wisdom, comfort and calmness to two generations of coaches, players and administrators.

It’s this apparent contradiction, between the havoc he once imposed on the field and the bottomless calm he instils off it, that gives the biography its title, Neil Balme: A Tale of Two Men.

The difference between the raging bull (the one the astonished Balme kids later saw in old TV footage of his most notorious “hits”) and the gentle husband and father they knew was always a thing of wonder in his own family. Likewise, in the football families he has fostered at five clubs, four in the AFL and at Norwood in South Australia.

Balme has spent longer than anyone else in the whiteboard jungle roamed by hundreds of coaching, medical, psychological and athletic staff across the AFL. He’s apparently top of that food chain as well, with little obvious effort.

He was a revered and successful playing coach at Norwood in the SANFL, and a loved though statistically unsuccessful coach of the Gutnick-era Melbourne side. But the man old enough to have rucked with and against the 1960s icon “Polly” Farmer came into his own in a role he made all his own.

He has had several titles at three powerhouse clubs but it’s hard to define exactly what he does, only what happens when he’s around. Balme’s stints at Collingwood, Geelong and, now, back with his first love, Richmond, have coincided with premierships at each.

In all, he has played a part in 11 premierships. Insiders call him a different four-letter word from the 1970s ones. It’s “guru.”

He certainly is original. It was Balme who asked the darkly humorous writer Cameron to get his story on paper before it’s too late. An oddball team selection, but it works.

Cameron is used to imagining characters and dialogue but has found Balme’s life a rich vein of the real thing.

Such as the day in 1969 when the teenage Balme, fresh from Perth, was standing outside his new school, University High.

A hot Torana pulls up. At the wheel is Robbie McGhie, unemployed apart from playing for Footscray. Told that the kid in front of him is Balme, just signed by Richmond, McGhie lights a smoke, bangs a tattooed arm on the car door and bellows: “We’ll meet one day, Balme. We’ll meet on the footy field. I’m gunna bash ya!”

Then he drops the clutch and fishtails up the street. Welcome to the big time, kid.

McGhie bashed half the competition, but he never did bash Balme.

Neil Balme: A Tale of Two Men. Viking. RRP $34.99