How notorious mafia boss was nailed almost three decades after bombing

It took 28 years, a million-dollar undercover budget and the most covert sting in police history to finally nail notorious mafia boss Domenic Perre.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

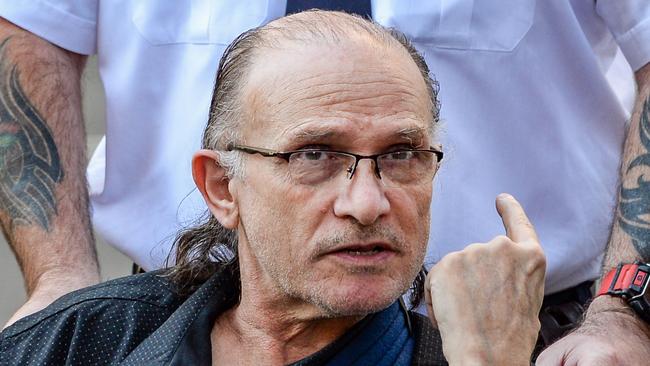

Domenic Perre, a callous mafia figure with no conscience, now seems doomed to die where he belongs — in a jail cell, twisted and bitter and an object of contempt.

It has taken 28 years for the law to punish Perre for making a letter bomb to kill a man doing his job as a National Crime Authority investigator.

Last week, a judge found Perre guilty of the bomb outrage after a 11-month murder trial nearly three decades overdue, a delay that rakes up old suspicions of corruption in high places.

The conviction, based on a strong circumstantial case, reverses what happened when a much younger Perre walked away from charges laid against him in Adelaide in 1994 following his rushed arrest a week after the bombing, which killed Det. Sgt. Geoffrey Bowen, father of two, and badly injured his colleague, lawyer Peter Wallis.

Perre walked again in 1997 after South Australia’s first Director of Public Prosecutions, hard-drinking compulsive gambler Paul Rofe, insisted on a “nolle prosequi” on the bombing charge.

Rofe would resign in controversy after a separate scandal in 2004, when he brokered a plea bargain that saw a rich man’s son released on $100 bond for shooting an innocent delivery man through the eye.

Rofe died in 2013, the target of whispers that his personal vices had compromised him with the sort of people who controlled clubs and brothels and fixed horse races and, possibly, legal cases.

Whatever the reasons, legitimate or otherwise, the bombing officially remained unsolved for another two decades. But there was only ever one viable suspect for it: Domenic Perre, the man a coroner named as Bowen’s killer in 1999.

The bomb that killed Bowen and ruined Peter Wallis’s life was as devastating as the Russell St police station bombing in Melbourne eight years earlier.

The NCA bombing targeted Bowen, who led the case against Perre over a mafia cannabis crop in the Northern Territory. The bomb was triggered when the detective opened a post box at the NCA’s 12th floor office in central Adelaide.

The bombing was a barbaric attack on the law — a version of the mafia terrorism waged against police and judiciary in Perre’s birthplace in southern Italy.

The hatred that led to the bombing was also fuelled by mutual animosity, heightened by Bowen’s pointed humiliation of the arrogant Perre by placing pornographic material on his bed when investigators ransacked the family house.

The inside story of how Perre was finally nailed began a year after the bombing, when South Australian police sought outside help to bring the prime suspect to justice after the initial charges against him failed.

In early 1995 South Australia’s police chief asked his Victorian counterpart if undercover police who had recently successfully infiltrated the Calabrian mafia in Griffith could get close to Perre.

The Victorian police hierarchy directed the approach to a key Griffith undercover investigator. Could he set up a sting against Perre?

The investigator, Colin McLaren, went to Adelaide to study every scrap of intelligence on Perre and his tight knit group, many of them related by blood, marriage and membership of the secret criminal society known as ’Ndrangheta.

The aim was to link Perre to the bombing. But the bonus would be that in doing so they might link him to wholesale drug manufacture.

There were never any other suspects for the bomb. Perre’s violent hatred of Bowen was well-known before the murder, a hatred which informs why Perre drove to a vantage point overlooking the bombed building in the hours after the explosion.

Perre’s gloating near the bomb site was one of many circumstantial elements pulled together later, including the mafia man’s access to bomb-making manuals and materials.

McLaren concluded that the best chance of getting evidence linking Perre to the bombing was through proving his access to the key materials in the bomb — notably red phosphorus, an explosive material also used in a hazardous method of “cooking” illicit methamphetamine.

The plan meant gathering a “crew” of undercover operatives to pose as hardened crooks without being exposed by Perre’s well-connected private investigator, who checked the background of anyone the crime boss did “business” with.

McLaren told the South Australians he would need nine months and a million-dollar budget to put together a team with deep cover stories then weave a convincing scenario without spooking the notoriously wary Calabrians.

His face had been too exposed in the Griffith sting to risk going undercover himself. Like a film director, he secretly recruited seven unknown faces from interstate to play specific parts in a production in which the ammunition was live, the blood wasn’t fake and the chemicals could blow you apart.

He had to bait the hook by introducing expert “speed cooks” into Perre’s circle who could sidestep the wiseguys’ intuition. The operation had to be kept totally dark to prevent a leak.

McLaren could not use anyone too young, as seasoned mafiosi would not trust “kids”. Any false note could be fatal. But there were two vital players in the troupe whose parts were strictly hands on.

One was reputedly the smallest policeman in New South Wales, a man in his 40s known during the sting as “Jimmy Anderson”.

Jimmy had joined the force after the minimum height rule was scrapped in the 1980s, and was a knockabout at ease with criminal slang. He was to play the “glass man”, a vital part in any amphetamine cooking enterprise which has to find highly-restricted laboratory equipment needed to process precursor materials.

But the masterstroke was finding a mature-age Maori police recruit in Victoria, a tough Kiwi-born copper playing the part of a tough Kiwi-born crook using the name “Jack Pahia”.

Jack had faded, homemade tattoos left over from a misspent youth in New Zealand, gaps in his teeth and the sort of lived-in face that comes from rugby. This was the man who could effortlessly pass as a “cook” — but only if he learned how to handle lethal chemicals with ease.

Jack did a crash course in “speed” production with the Victoria Police forensics chief scientist. Precursors for producing amphetamines are notoriously unstable and dangerous, especially using the red phosphorus method.

Of the seven undercover operatives, two posed as an unhappily married couple: the “husband” playing a violent Calabrian with criminal connections (notably Jack the speed cook) and the woman as a runaway prostitute from Melbourne.

The others posed as the troubled couple’s friends to corroborate their backstory. The elaborate deception meant carefully constructed family albums, bank accounts, drivers’ licences, travel documents, rent agreements and car registration — enough to withstand scrutiny from Perre’s private eye.

Ten surveillance experts worked shifts around the clock to keep the seven players safe if the sting turned sour.

It was a huge task. One thing the “stingers” had going for them was that Perre was anxious to make money after losses from the big Northern Territory cannabis debacle.

Perre hired Jimmy to supply the laboratory gear and set up Jack Pahia on a farm near Adelaide owned by members of the Trimbole family. The stingers hoped that because Perre had spent $60,000 on the clandestine laboratory, he’d be so desperate for the expected $20m profit that he might drop his guard.

At first, Perre avoided any part in obtaining red phosphorus. He would mouth the word “bomb” and make signals when the subject was raised, insisting that Jack had to source the phosphorus independently because he couldn’t risk doing anything linking him to the bombing.

Jack made a show of getting Sydney contacts to ship the phosphorus to Adelaide by train. The stingers had to sabotage that supply to force Perre into the open.

Police stopped the train in NSW, grabbed the bag of phosphorus and tore it as if it were damaged in transit, then poured water into it, as if the freight car had leaked.

After the bag was delivered, Perre was stunned when Jack told him the bad news: the phosphorus was ruined and the multimillion-dollar venture was under threat.

Perre had sunk his shrinking cash reserves into the scheme and couldn’t bear to walk away. So he did what he had dodged until then: he arranged an alternative phosphorus supply, a deal caught by police cameras and listening devices.

Meanwhile, Perre’s new best friends heard him refer audibly to the bomb. He spoke bitterly of Bowen’s activities against him — and boasted he should have blown up more police.

When the drug was almost ready to sell, police arrested Perre and five other mafia figures alongside Jack and Jim and the Calabrian undercover operative. They also reeled in a shady gunsmith who had “minded” illegal guns and bomb making texts and materials for Perre.

It was the most complex covert sting in Australian law enforcement, complete with secretly recorded evidence.

The evidence of the drug plot was unassailable and earned Perre and his people stiff jail sentences in 1997.

But Paul Rofe the chief prosecutor and problem gambler insisted the evidence implicating Perre in the bombing was unusable, arguing that the undercover operatives were “agent provocateurs”. Rofe flatly refused to prosecute Perre for murder. This seemed a wonderfully lucky break for Perre, despite his drug conviction.

McLaren’s team was angry and disappointed. McLaren handed over audiotapes to the prosecutor’s office but refused to part with notebooks and files with detailed notes on Perre’s damning admissions. He would quit the force and move many times in the following 20 years but he kept the notes safe from those who might want to destroy them.

After the disgraced prosecutor’s resignation and death, his influence faded. In 2015, South Australian police found that a robust new prosecutor would revive the murder case against Perre.

It took time. Last year, McLaren finally produced his cache of notes and testified against Perre. So did Jack Pahia. But Jimmy Anderson the “glass man” died in 2020 and missed his day in court.

Anderson’s testimony wasn’t the only thing the case was missing. Strangely, the audiotapes McLaren had provided to Rofe’s office in 1997 had vanished, although it was hardly mentioned by either police or prosecutors.

There was enough corroboration to convince Judge Kevin Nicholson that Perre was guilty. Which means, he should die in jail.

But the question stands: did he buy his way out of murder charges for 26 years?