Andrew Rule: The day bank robbery’s golden era ended

It’s July 22, 1991 and a crook pinned to the roof of a bank by bulletproof shutters is slowly dying — it’s the day that symbolises the end of bank robbery’s golden era.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Steven Charles Kovacs died broke and alone. It took him 15 minutes to run out of breath, a long time for a would-be bank robber to face his mistakes.

That’s how it goes when you try robbing a bank just after it installed bulletproof shutters set to go off at the touch of a trigger.

The steel plate caught Kovacs by the neck and pinned him to the ceiling a second after he made the last of a long list of bad choices: jumping the counter of the St Leonards branch of the Advance Bank just as a teller hit the panic button.

The new machine launched the shutter, catching Kovacs’ neck against the ceiling like a rat in a trap.

The terrified crook dropped his weapons and screamed “Bernie, help me!” to his accomplice. But it was no time for honour among thieves. Bernie bolted outside and down the Pacific Hwy.

Other staff and customers also ran from the bank. They didn’t realise Kovacs was dying until the police arrived.

He was no great loss. As a policeman told a Sydney coroner, Kovacs “lived a manic, heroin-addicted lifestyle” and had a long criminal record. But his demise highlighted the risks of taking on modern bank security.

It was July 22, 1991. A date that symbolises the end of bank robbery’s golden era.

Armed robbery squads went from chasing a robbery a day to a couple a month, and dwindling.

Like skin-tight flares, skinhead rat tails and Gary Glitter, bank robbery ruled in the 1970s and 1980s and vanished in the 1990s. By 2000, it was consigned to history and Hollywood.

There were still armed robberies, but of cheap targets like service stations, pokie venues and junk food stores. The people who pulled them were mostly “desperates” with drug habits.

The armed robbers who’d been the aristocrats of crime were dead, in jail or had changed jobs. The new order was all about drugs. If the heavies weren’t importing or supplying street dealers, they were “minding” those who were — or standing over them.

Banks had won the “arms race” with bulletproof screens and security cameras, then DNA and mobile phone monitoring.

The last coffin nail was the demise of cash. Pay packets vanished before the end of the century. Two decades later, the Covid pandemic merely accelerated the inevitable trend towards using electronic money.

Bank branches now have negligible cash compared with the old days. Most people handle funds online, not in wallets and bags, making online scams the high-growth crime of our time.

Like safe crackers, the bank robbers of old are almost all gone but the best of them are still seen as crime royalty. When cash was king in the jungle, those who took it by force were admired by lesser beasts.

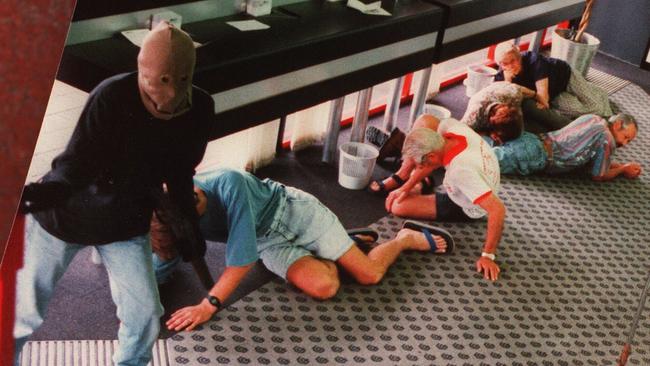

In reality, of course, armed robbers inflicted lasting damage on innocent people. But their notoriety still lingers.

A nation settled by convicts always had its robbers. In late 1828, five men tunnelled under the new Bank of Australia in George St, Sydney, and got away with £14,000, a staggering sum at the time.

Bar a few bushranger raids, it would take until the gold rushes of the 1850s and 1860s for armed robbers to start pulling serious stick-ups.

The fact that gold was moved by stagecoach led to one of the most brazen hold-ups in history. On June 15, 1862, a dozen armed men in red shirts, with faces blackened, hijacked bullock teams to block the coach road at Eugowra Rocks in western NSW.

The Bathurst to Forbes coach had a police escort because it was carrying a fortune: £3700 cash and 2717 ounces of gold, around $8.5m in modern terms.

The gang was Ocean’s Eleven on horseback, pulled together by bushrangers Frank Gardiner and Ben Hall and including notorious figures like John Gilbert and John O’Meally.

Gilbert, O’Meally and Hall would be killed by police over the next three years. Gardiner was eventually arrested but released after only eight years of a long sentence and deported to San Francisco, where he ran a saloon and died a free man. No one knows if he got away with much of the gold escort proceeds or why he was released so early.

Gardiner’s audacious heist came the year before America’s first known armed bank robbery. In Australia, after the bushranger era ended with Ned Kelly’s hanging in 1880, a new breed of robbers and safebreakers stepped up.

Two world wars changed society. More guns hit the black market following the influx of American R & R troops and returning Diggers.

Among battle-hardened ex-soldiers were some willing to take risks to make fast money. A few joined police forces, and got along with hard men on the other side of the law.

In Sydney, and possibly elsewhere, bent detectives like Roger Rogerson “green lighted” robberies in return for a cut, providing no civilians or police were hurt.

In the 1950s and 1960s, bookmakers turned over huge sums as returned soldiers loaded with deferred pay hit the racetrack to gamble and drink, inflating a cash bubble that lasted until long after the birth of TAB agencies.

More cash changed hands than at any time since the gold fever of a century earlier. And where there’s cash, there are always those wanting to grab it by stealth — or force.

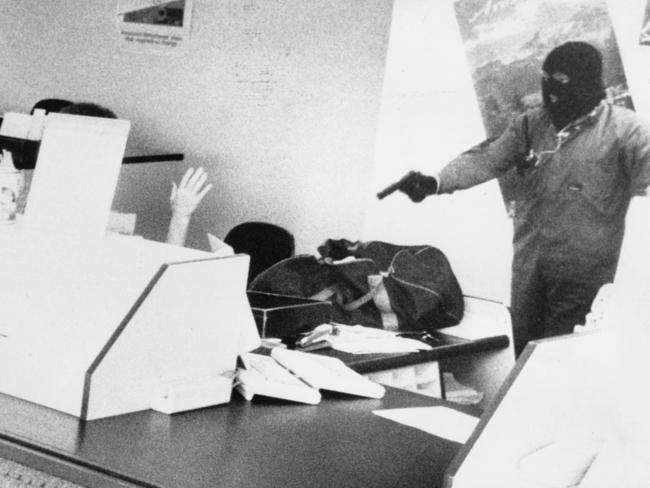

By the 1970s, robberies were almost daily. Heavy hitters mostly hit banks, armoured cars and payrolls, and the new TAB agencies got their share of “counter jumpers” on big race days.

One of the maddest and baddest robbers was Christopher Dean “Badness” Binse, whose first armed robbery was of a TAB in Melbourne’s west.

Binse has since been convicted of armed robbery seven times, has escaped custody twice from six attempts and has had more than 100 convictions in total.

His obvious nerve and reflexes haven’t saved him from wasting all but four years of adult life behind bars. At least he is still alive, unlike the crew that pulled the Great Bookie Robbery in 1976.

It was arguably Australia’s biggest heist, relieving 116 Melbourne bookies of millions on a bumper settling day following Easter race meetings.

It’s hard to measure the robbery against other heists because no-one alive knows exactly how much the well-schooled gang scored at the Victorian Club that day.

Officially, the take was $1.4m. But some bookies admit they were insured for less than a third of what they actually lost in undeclared cash.

If that was true for most of the bookies, maybe the total haul was up to $6m. Underworld sources suggest it was that much, but inflated media guesstimates of “up to $15m” are delusional.

Bank (and armoured car) robberies took over in a hectic era when old-school safebreakers decided modern safes were getting too hard to crack. A notable exception was Melbourne’s “magnetic-drill gang,” which pulled off the massive Murwillumbah bank safe heist in late 1978.

From John Dillinger to Ned Kelly, outlaws held up banks because, in the alleged words of the American robber and jailbreaker Willie Sutton, “that’s where the money is.”

Whereas safecracking required patience, technical skill and special equipment, stick-up men needed only a gun, a stolen car and some dash.

By the 1970s, Australia’s post-war economic and migrant boom had created new suburbs and new bank branches and building societies. Each branch held bulk cash, which had to be moved regularly. Movement of armoured cars and bank staff was easy to monitor.

Security cameras were rare or primitive. A passer-by could “case” a branch, noting layout, staff members, quiet times and escape routes.

Stick-ups were a tempting way to make “a good earn” at the risk of sudden death or slow jail time. Robbers didn’t necessarily need to be part of a criminal network the way a drug dealer (or even pro shoplifters or burglars) had to be. They didn’t have to “fence” cash — just spend it.

And they did. Most robbers “torched” stolen money on gambling and other vices. The exception to the rule, maybe, is Russell Cox, who actually bought a country retreat in Queensland while on the run from a prison escape for 11 years.

By contrast, Cox’s contemporary escapee Raymond Denning, took his $110,000 whack of a huge payroll robbery — and lost it all at the races. Denning ended up dead, probably by a heroin “hot shot”. Whereas cool hand Cox married his longtime partner and left jail, vowing never to return. He hasn’t.

“Good crooks” with the brains of a Cox or his bookie robbery mate, the late Ray Chuck (alias Bennett), wouldn’t go near a bank these days even if it was handing out free beer.

As one veteran armed robbery investigator of that era said this week, for real robbers the risk has far outweighed reward for many years.

There’s so little cash in modern banks that they are as safe as insurance offices or travel agents. These days, statistics show, it’s more dangerous to work on the front desk at Centrelink.