Andrew Rule: Grotesque crime still haunts all involved 58 years on

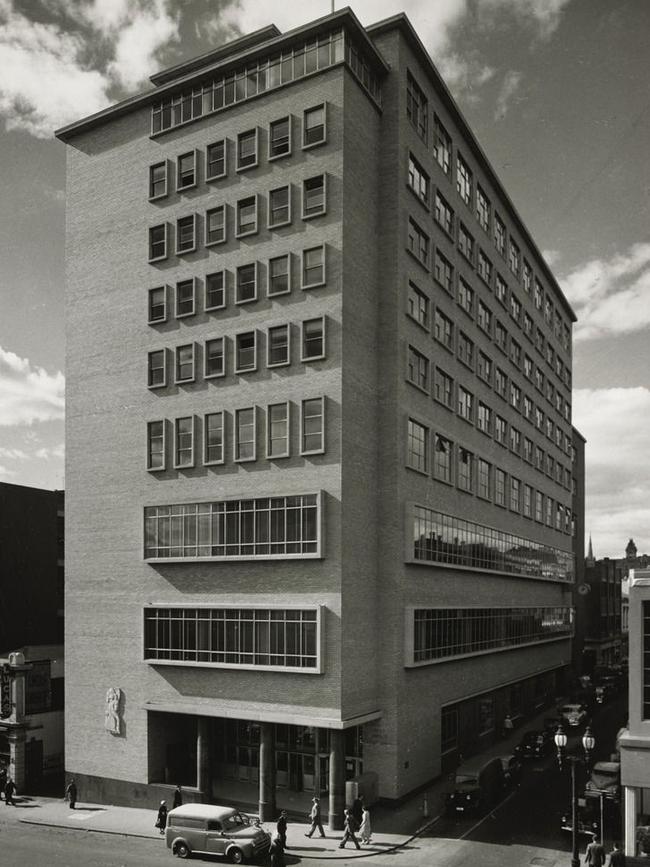

On May 3, 1965 someone walks into the post office on the corner of Russell St and Little Collins with a parcel. What unfolds from there is one of the most grotesque crimes in Australian history.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It is 20 years this month since Katherine Folbigg was jailed after the separate deaths of her four children.

Folbigg could be the most tragically unlucky Australian mother since a South Australian farmer’s wife named Maggie Smith lost six of her seven sons in World War I, with the seventh killed “accidentally” after returning from the front.

What we know now that we didn’t know when Folbigg was jailed in 2003 is that she deserves the benefit of new and serious doubts.

Those doubts arise from scientific advances which convince independent lawyers that two of Folbigg’s doomed babies had deep-seated genetic conditions which might have caused their deaths.

This, of course, does not account for the two other dead babies. But maybe one day medical science will manage to explain those “cot deaths”, too.

Meanwhile, it seems reasonable that this tragic figure be freed to face what’s left of her fractured life. She is hardly a risk to society. If she really is guilty then nothing can punish her more than the torment of being responsible for her unspeakable losses.

What the Folbigg case tells us is not how intolerant we are of babies being harmed — but how tolerant we are of mothers suspected of infanticide. Here’s the proof: if Folbigg’s fourth child hadn’t died, she would never have been prosecuted over the first three deaths.

Modern society’s default attitude is that mothers would do anything to protect their children. Mostly, that is true. But it doesn’t alter the confronting fact that infanticide has been a constant since our forebears lived in caves.

It turns out there is another anniversary this month — of a grotesque case in which there’s little doubt the mother killed her child or played a part in it.

The story begins on May 3, 1965. That Monday, in Melbourne, someone walks into the post office at the corner of Russell St and Little Collins carrying a parcel wrapped in brown paper.

In 1965, post offices are hectic. Thousands of letters and parcels are mailed all over Australia every day. There’s no reason for busy staff to note who posts which item.

There are no closed-circuit cameras, no x-ray machines and none of the security paraphernalia that later becomes standard.

The shapeless parcel handed over the counter to be weighed and stamped is just another anonymous piece of mail. A casual observer might guess it contains clothing. Perhaps baby clothes for a new arrival in a distant family.

The parcel is addressed to “J. Anderson”, care of the Knuckey St post office in Darwin. The return address is in the bayside suburb of Mentone.

By the end of the week, the parcel reaches the post office in Darwin. No one claims it.

On Tuesday, May 11, there’s a foul smell in the mail room coming from a soggy parcel, oozing something bad.

A clerk opens the putrid package and for the rest of his life wishes he hadn’t.

It’s the body of a male baby, umbilical cord still attached. A nylon stocking is pulled tight around the tiny neck.

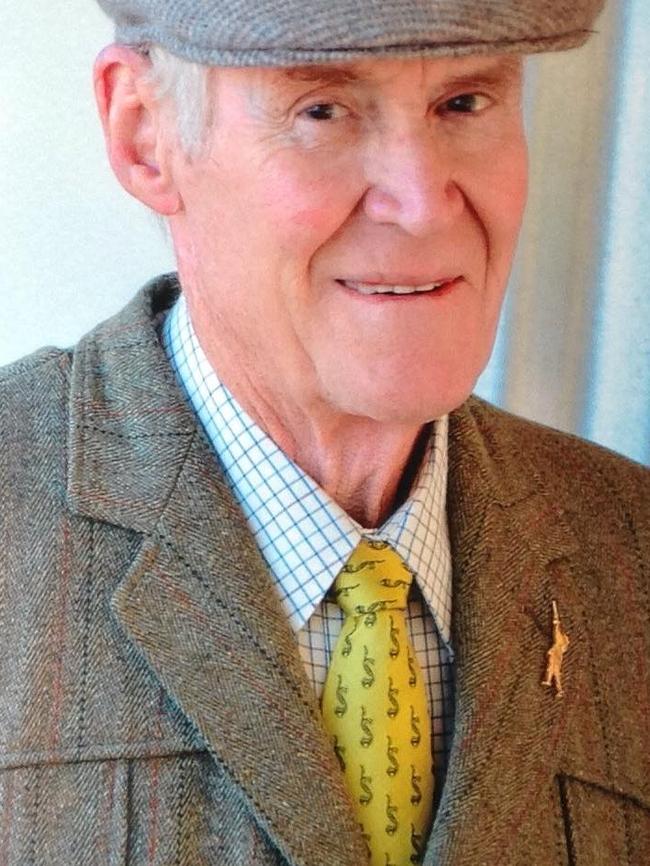

When Darwin detective Denver Marchant arrives, it’s the beginning of a fruitless investigation that will haunt him forever.

At 81, deep in retirement in Queensland, Marchant officially left the baby-in-the-mail case behind long ago. But it won’t leave him.

Sometimes, reporters ask him about the mystery. Recently, crime podcaster (and former Sydney cop) Meni Caroutas talked to the old-timer for his new series The Missing Australia.

Caroutas once worked the beat in Kings Cross and saw street life through a policeman’s eyes before switching to investigating as a reporter.

He struck an easy rapport with the retired detective while interviewing him for the podcast, chasing details in a story that is part of Darwin folklore. But if there are any answers to be found, they are probably in Melbourne.

Starting with the return address on the parcel.

The sender’s name was written as J.F. Barnes, 2 Woolridge Ave, Mentone. Police found no J.F. Barnes near Mentone, certainly none that could identify the baby’s mother. And there’s no Woolridge Ave anywhere in Australia.

As for the addressee, police could find no “J. Anderson” in or around Darwin.

So who posted the macabre parcel and why?

Caroutas sketches a couple of scenarios. He suspects a motive of revenge — if not a spurned woman avenging herself on the runaway father of her unwanted baby, then perhaps a cuckolded husband (or angry father) taking a hideous form of vengeance for a rape or seduction.

But there could be a third scenario, thrown up by the fact that Darwin (like Perth) always had a powerful grip on Victorians’ imagination because it’s about as far from Melbourne as you can get.

Traditionally, east coast fugitives would head to “the Top End” or to the far west to be as far as possible from pursuit.

The Darwin of the 1960s was a faraway place where someone desperate and agitated enough to have killed their baby in Melbourne might well decide to send the body to get rid of it.

Sending the little corpse in the mail was grotesque but not irrational.

For a start, it makes sense to have wrapped the tiny body like a parcel to prevent suspicion while moving the baby from where it was killed.

With the body already wrapped as a parcel to move it, the step of posting it far away rather than risk being seen burying it could easily have occurred to a fear-filled mother — or someone close to her.

Taking the anonymous package to a post office was a failsafe way to remove the body far from the crime scene without any risk — and to gain at least a week’s lead on any possibility of an investigation that would inevitably be hamstrung because it was in a police jurisdiction as remote as Siberia is from London.

It was bizarre, but also an efficient method of getting rid of evidence of a crime that has historically always been more common than we moderns like to think.

The fact is, our ancestors knew more about infanticide than we do. Killing or abandoning babies was once so common it accounted for many of the high number of infant deaths before 20th century medicine started saving lives among poor people in crowded and unsanitary conditions.

That desperate mothers killed or ditched unwanted babies was an open secret, so common that the crime of “infanticide” has always been held, both under the law and culturally, as a lesser offence than murder.

In colonial Australia, historians say, close to half the homicides prosecuted against women were for killing babies. Even that ratio under-estimates the true rate of infanticide, which was a hidden crime carried out by desperate women terrified of the catastrophic stigma of having “a bastard” child, or simply unable to support an extra mouth to feed.

Until the 1920s, such women were routinely cleared of murder, instead being charged with concealment of birth and sentenced to a mere two years prison. But this applied only to unwed mothers.

Of course, poverty-stricken married women also had a motive to kill newborns and pass them off as still-births. In theory, they were liable to be prosecuted for murder or manslaughter but few were.

The bitter truth was that many were forced to face a terrible option we would now liken to “Sophie’s Choice”, having to kill a newborn so an older child could survive.

For all of human history, infanticide has been practised across most cultures but, if done by the birth mother, regarded as distinct from murder of older children or adults.

The law in three Australian states still reflects this traditional tolerance. Infanticide is legally a less serious crime than murder in New South Wales, Tasmania and Victoria.

In the first two states, infanticide is technically punishable on the same scale as manslaughter, though it never is. But in Victoria, the maximum sentence for infanticide (of a child up to two years old) is only five years — and, in reality, the few mothers convicted of it are rarely jailed.

In a nod to the ancient tolerance of infanticide, women who kills their own babies in Victoria in 2023 do not need proof of a severe psychiatric disorder to avoid prison. The catch-all label “postnatal depression” is enough.

This all means that the mystery mother of the dead baby boy posted to Darwin in 1965 need not be terrified of the consequences.

If she’s alive, she would probably be in her late 70s to mid- 80s. If a woman that age finally comes in from the cold to unburden herself from her 58-year secret, there’d be little to fear from the law.

Unless, of course, she was driving a zimmer frame in a dangerous manner in a nursing home and a twitchy cop decided to taser her. As if that would ever happen.