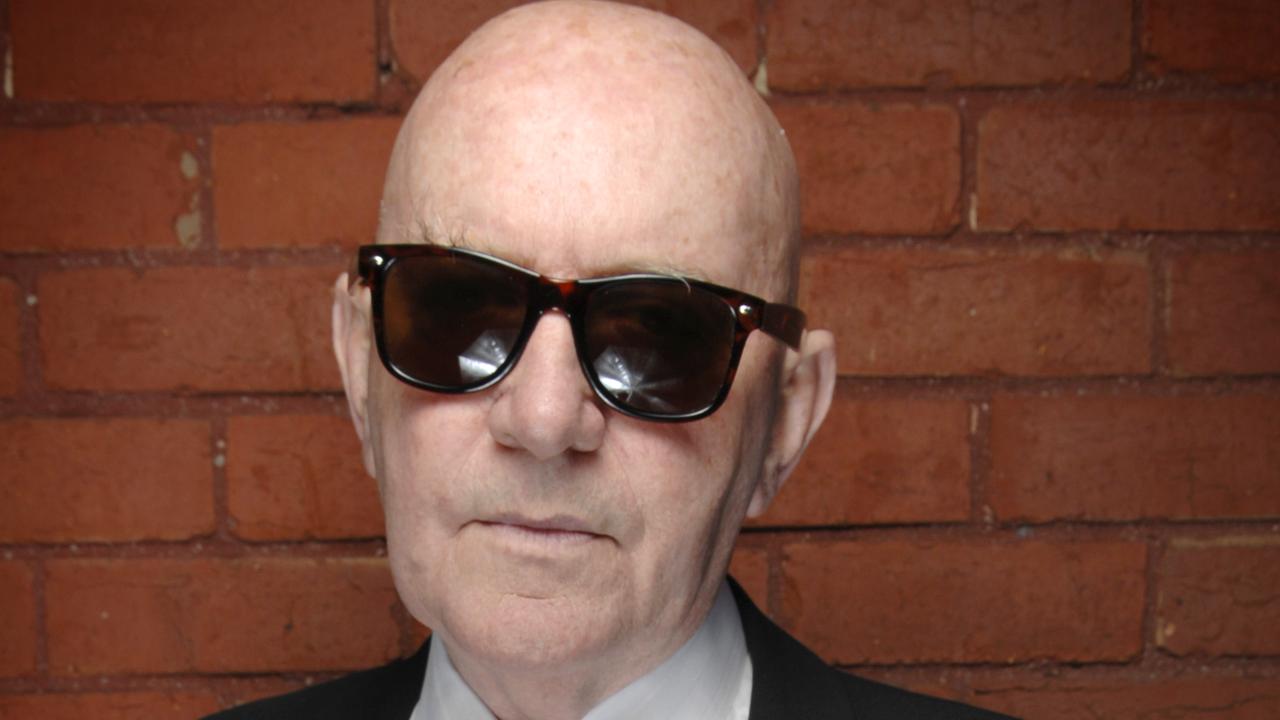

Andrew Rule: How Brian ‘The Skull’ Murphy lived up to the legend of the tough cop

Only a few former cops are old enough to have known Brian “The Skull” Murphy in his prime, but right up until his death — on Anzac Day — he divided opinion.

If Brian Francis Murphy hadn’t invented himself, someone else would have had to: creating the legend of a flinty copper who ruled the streets with iron fists, staring down bad guys with hard blue eyes.

To do Murphy credit, he was playing his part well before another exponent of the lethal glare, Clint Eastwood, perfected Dirty Harry Callaghan.

Now that Murphy has died, his legend will get a big run at his funeral. His family is entitled to do what we all do, which is to paint the departed in the best light.

Funerals are different from courts, where witnesses swear to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but — a rule that Murphy treated more as a rough guide.

In eulogies, the departed invariably gets the best of rose-tinted glasses and sentiment.

“A man’s man” is a bash artist and sexual predator. “A ladies’ man” is a con artist and sexual predator. “A yarn spinner who loved a drink” is a drunken liar.

As a dedicated teetotaller, husband and father, Murphy was none of those things, except for belting crooks. He was more the “hard man, tough but fair” right up until he died on Anzac Day soon after another eccentric figure he knew well: Father Bob Maguire, the unorthodox Catholic priest whose longtime South Melbourne parish was the unorthodox policeman’s home turf.

If Murphy had secrets, maybe they died with Maguire or with Murphy’s admired barrister brother, Brendan, whose death last Christmas shook him.

Only a few ex-cops are old enough to have known “Skull”, alias “the Bald Eagle”, in his prime. They describe a man of contradictions.

One former crime squad veteran, no stranger to fisticuffs and gunplay, this week recalled being with Murphy in a city street in the 1970s when they noticed an angry young man yelling at a scared young woman.

Murphy approached and calmly asked what the problem was. The politeness was bait. The bully made the mistake of swearing at Murphy, who hit him very hard without any warning. End of discussion.

As usual, Murphy had the advantage of surprise and guile, plus the punches learnt as a schoolboy boxer and street fighter. And the confidence that comes from carrying a gun and badge.

Even when he no longer had the badge he reputedly had a gun. He certainly did the day he caught a man breaking into his neighbour’s house.

The burglar turned nasty and told Murphy he was too old to stop him. Murphy shot him in the foot. Another time he poured petrol on two drug dealers in his street.

Murphy was kind to women and kids but most others were fair game. Uncooperative crooks, for instance.

~ FOLLOW ANDREW RULE’S UNDERCOVER COP PODCAST ~

One detective recalls working in the northern suburbs at the time “Skull” led a police unit informally known as “Murphy’s Marauders”, whose unofficial job was to terrorise criminals.

One day, the detective arrested an active criminal at Broadmeadows. Soon afterwards, Murphy and his men arrived, wanting to take the crook “for a ride”.

The arresting detective refused to let the accused go. After Murphy left empty-handed, the deadpan detective said to the crook: “I think I just saved your life, mate”.

Murphy had that sort of reputation. Hardly surprising, given he spread it himself.

He assured one thrilled biographer he’d shot and wounded 40 people. He only half-heartedly denied the gratifying rumour it was he who shot dead Ray Chuck, a.k.a. Bennett, at the old City Court in 1979.

Murphy’s artful suggestion was that the shooter was indeed called Brian: the actual killer being Brian Kane, a standover man who’d disguised himself in a beard and spectacles to avenge the death of his brother Les.

The killer’s escape route through a labyrinth of stairs and doors and a garage was surely mapped out by rogue police linked to Murphy.

The Kane brothers were, it happens, close to Father John Brosnan, Pentridge Prison chaplain and friend of James “Jockey” Doyle, a sawn-off gunman that Murphy had befriended in the 1950s.

It was a time when cops picked sides in the underworld, often on sectarian lines.

Born in a generation shaped by war

Brian Francis Murphy was born at the height of the Depression and grew up poor in Port Melbourne during a world war that shaped his generation for better or worse.

He could so easily have gone the wrong way. Maybe it was his mother’s fierce Catholic faith that kept him from the worst company, although it didn’t quite save him from a paedophile who preyed on altar boys at their church.

Murphy’s breezy published account of this incident has him escaping the man’s clutches after being conned into a grubby boarding house, but his towering rages as a young man suggest the one-time altar boy had altered.

He took pleasure, he said later, in catching up with the offender several years on, and he hammered perverts who hung around schools, playgrounds and parks.

But it wasn’t only soft targets that Murphy rattled with an unsettling blend of brutality, vanity and insanity.

Lewis Moran, fighter, thief, drug dealer and sometime gunman, was once in a holding cell in South Melbourne police station, a district he’d been warned to avoid.

Moran heard the hatch open and saw a revolver appear. He recognised the hand holding it as Murphy’s and dived to the floor as bullets hit the back wall.

This calculated craziness was all part of the Skull show. He radiated a reality distortion field fuelled by charisma, bravado and obstinacy.

This reporter met Murphy a handful of times and called him occasionally after he’d left the force in the late 1980s. Retired, he still went around town like a sharply-dressed detective, down to the camel overcoat, hat, pressed suit, diamond tie pin, spit-shined shoes and perfect shave.

I met him once in a pub with the enigmatic horse trainer Les Theodore, again at the home of a racing identity close to one of Australasia’s biggest illegal bookies — and twice with the late Billy “The Texan” Longley, the old-time waterfront gunman reputed to have killed a dozen men.

Longley was a little older than Murphy, but shaped by the same forces: Depression, war and respectable working-class poverty. Whereas Longley rose from street fights to gunfights on the wrong side of the law, young Murphy signed up on the right side.

What the future strongarm cop and the future painter and docker each had was nerve, the sort of granite self-belief and sense of theatre that intimidates less dominant personalities.

There were better fighters around than either of them, but mere ferocity didn’t make up for sheer “front” and readiness to shoot first. Both were tough — but also full of bluff, with the poker face, unblinking stare and ruthless cunning.

No wonder “Skull” and “The Texan” ended up joining forces as “negotiators” at an age when most grandfathers are happy with gardens and bowling greens. Intimidation is a hard habit to give up. Collecting debts is much better than working.

Longley died in 2014 but Murphy lived on, ignoring the Grim Reaper until last Tuesday.

As an old man who’d outlived most contemporaries, he told various sanitised “Boys Own” versions of his life to enthusiastic biographers who played to his vanity. Even in his last months, he was telling yet another version of his life story to another eager fan.

By contrast, those who knew him in the police force tended to be wary about Murphy. All his life, he divided opinion.

Even senior police who had exploited Murphy’s tough tactics were careful of publicly associating with him. He was rarely asked to testify in court because of a tendency to make outrageous fabrications or mischievous asides to embarrass or discredit anyone he disliked, even lawyers or other police.

He once threatened to bite the nose off an accused in court, to the horror of the magistrate. But at church on Sundays he would kiss babies, help old ladies and pass the plate. He doted on his wife, Margaret, their five children and a mob of grandchildren and great grandchildren.

If Murphy was Jekyll and Hyde, the Hyde bit won’t be getting a run at his funeral. Topping the list of sins is that he and another cop allegedly beat a thief named Neil Collingburn to death in 1971.

Murphy and his co-accused were acquitted of Collingburn’s manslaughter. Other scandals and accusations led to inquiries and death threats but nothing stuck.

A perplexed reporter once wrote that the more investigators scoured Murphy’s bank accounts and looked for cash and hidden investments, the less they found. Likewise with complaints of assault and bribery, bombings and shootings, and allegations he protected certain crooks.

Maybe the biggest black mark against Murphy was his relationship with a notoriously bent cop, Paul Higgins, who served five years jail after a seven-year trial that cost $33m to prove Higgins took bribes from heroin-dealing brothel king, Geoff Lamb.

Higgins was younger and meaner than Murphy, which made him a useful ally. He was a savage fighter who held the police heavyweight boxing title and was feared by many police and crooks and distrusted by most. Unlike Murphy, he was a rapist as well as a bash-artist.

Higgins and Murphy looked after the evil Dennis “Mr Death” Allen, a drug-dealing killer who informed on other crooks to stay out of jail.

What Allen also did was pay weekly bribes to his pet police, who gave him their home numbers to call if he was arrested by someone else. Allen once showed his lawyer a fat envelope with $14,000 in it — “a grand a day each for a week”, he said.

Did Higgins keep it all? Or did Murphy take his half of the dirty money and put it where it would do some good? Meaning his church.

Some retired police suggest the answer to that died with Father Bob Maguire, who was, it is said, a terrific fundraiser in the years he knew Murphy.