Andrew Rule: The cautionary tales in miscarriages of justice

History is littered with outrageous miscarriages of justice — but whether it’s stuff-up or conspiracy, for those convicted on dodgy evidence, the results are harrowing.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Police and prosecutors and judges and juries mostly get it roughly right. But that’s no comfort for those who suffer when human error, or something worse, taints an investigation or the subsequent court case.

Sure, “stuff-ups” might outnumber conspiracies but the difference hardly matters to the losers in the legal raffle. An honest mistake or a dishonest conspiracy is equally shocking for anyone convicted on dodgy evidence.

Legal history is littered with examples, and not only in cosy cowboy jurisdictions like Western Australia and the Northern Territory, where erratic police and legal standards have thrown up scandals for decades.

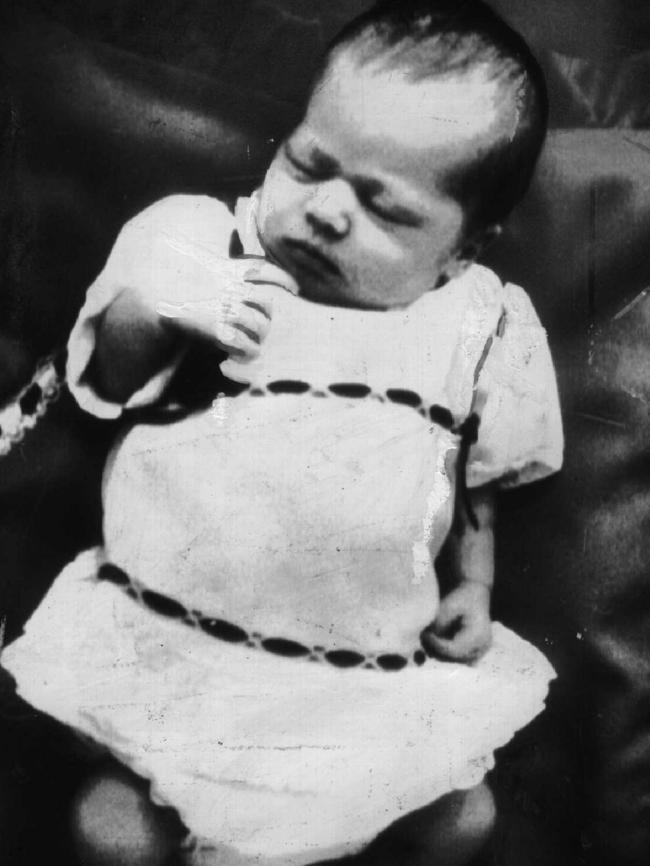

Exhibit A: the Chamberlain disgrace. “Territory” police, may be reflecting local political and business interests keen to clear local dingos of menacing tourists, influenced media coverage that turned public opinion against Lindy and Michael Chamberlain when their new baby Azaria vanished from their tent at Uluru in August, 1980.

Evidence that a scavenging dingo took Azaria was strong and totally logical. But that didn’t stop a boofhead detective from spreading ignorance by getting a bucket holding a baby’s weight (4.5kg) and showing he couldn’t carry it with his mouth for more than a minute, thereby “proving” a dingo couldn’t carry a baby any distance.

The stupidity of comparing a human mouth’s inability to carry such a weight with a dingo’s massively strong jaw went unchallenged by the policeman’s superiors, even though actual dingo experts would later testify to an apparently deaf jury that dingos routinely carry big weights with ease.

A case of dumb and dumber. Then dumbest.

The unequal relationship between influential police and a young and gullible forensic officer, Joy Kuhl, might explain the baffling fact that she misidentified sound-deadening paint on the Chamberlain’s car as “foetal blood.”

Although Kuhl’s nonsense theory would eventually be exposed by real scientists, it was enough to get Lindy Chamberlain locked up until the random discovery of Azaria’s jacket near a dingo den three years later. That got the case reopened, eventually leading to the wronged woman’s release after an eight year ordeal.

Interestingly, Territory police landed another unlikely (and timely) forensic coup 21 years later, when investigating the disappearance and presumed murder of English tourist Peter Falconio. The case against the man convicted of Falconio’s murder, Bradley Murdoch, relied heavily on a tiny blood speck apparently found on the shirt of the missing man’s girlfriend, Joanne Lees. Lucky, that.

The Chamberlain case was world-famous, thanks to the dingo. But other miscarriages of justice were no less outrageous. Such as the wrongful convictions of Daryl Beamish, John Button and Andrew Mallard, each man framed for a murder he didn’t do.

It still happens. Mine worker Scott Austic was recently released after 12 years, when authorities tacitly conceded he’d been blatantly “fitted up” in 2009.

The flipside of lazy policing in the west is that it allowed the shotgun death of Amy Wensley in a farmhouse in 2014 to be written off as a suicide, with the risk of it being a homicide being discounted without proper investigation.

Amy, who was right-handed, was found sitting on her right hand with the heavy gun a metre away. And she just happened to have her clothes, passport and two children packed ready to flee to her mother’s place minutes before she was shot.

Bagging Perth police is easy. These are the Keystone Cops who drove innocent public servant Lance Williams to a premature death with aggressive surveillance — and by briefing the media that he was the prime suspect as the Claremont serial killer.

In fact, of course, the actual Claremont killer of three young women was a man the police missed for 20 years, a quiet Telstra technician named Bradley Robert Edwards, finally arrested in 2016 after poor Williams’ life was ruined.

Closer to home, in South Australia, a charmed circle of well-connected sexual deviates got away with committing “the Family” murders while a totally unqualified chief forensic pathologist screwed up case after case for close to 40 years.

Dr Colin Manock gave erratic “expert” evidence that led to 400 convictions and performed thousands of autopsies he wasn’t qualified to do. Manock’s critics suggest he survived because he was “on side” with police, even if that meant drawing convenient conclusions that ignored inconvenient facts.

Victorians like to think that when it comes to police and legal corruption, jurisdictions north of the Murray are banana republics run on bribery and blackmail.

The fact that Sydney and Brisbane were so “hot” for so long doesn’t let Victorian law enforcement off the hook. The list of dodgy investigations and trials in Victoria is nothing to be proud of.

In 1922, Victoria hanged Colin Campbell Ross on confected evidence that he raped and murdered a 12-year-old schoolgirl, Alma Tirtschke.

Ross, a young publican disinclined to bribe bent police, was disliked by a notorious brothel keeper, Madame Brussels, whose nearby establishment was well-known to senior police and politicians.

The theory goes that Madame Brussels and corrupt police organised false witnesses to convict Ross and then pocketed the lion’s share of the reward posted to solve the terrible crime.

It wasn’t until amateur sleuth Kevin Morgan uncovered a forgotten sample of Alma’s hair among old legal documents in the 1990s that modern forensic science cleared Ross. He had been convicted and executed within weeks mainly on the false premise that hairs found on a blanket he owned were Alma’s. In fact, it was dog hair.

Another innocent young man could easily have been hanged after being repeatedly accused of a double murder at Shepparton in early 1966.

This was the abduction murder of teenagers Abina Madill and Gary Heywood. By the time the bodies were found 16 days later, “bash artist” detective Peter Parkinson had made Abina Madill’s sometime boyfriend, apprentice mechanic Ian Urquhart, the prime suspect.

Persistent police persecution of Urquhart over months forced him to leave Shepparton to work on oil rigs. If he hadn’t had the guts to withstand being beaten and abused, he could easily have signed a “confession” that would have been his death warrant.

The then longtime Premier Sir Henry Bolte was preparing for the 1967 election and boasted a hanging would win it for him. He was right.

Ronald Ryan and Peter Walker had escaped from Pentridge just before the Shepparton murders; Ryan’s shooting of a prison officer made him ideal for a politically-useful execution. But if Urquhart had been forced into a false confession of rape and double murder, he might have swung too — a Bolte bonus.

As it stood, some detectives blamed Urquhart until 1982, when a diligent fingerprint expert uncovered the fact that a tiny print secretly lifted from Heywood’s car in 1966 matched an unknown offender, the “Donvale rapist”, who’d raped dozens of women in the eastern suburbs in the 1970s.

Urquhart was finally exonerated — too late, as he’d died in a car crash. It would take three more years before fingerprints finally nailed the real killer: Raymond “Mr Stinky” Edmunds.

There are plenty more stories of stuff-ups and the odd conspiracy.

Such as the abduction and murder of Elisabeth Membrey at Ringwood in 1994: to date, police are on their third “prime suspect” after being mighty sure about the previous two.

Then there’s the Russell John Gesah debacle. In 2008, prisoner Gesah was charged on DNA “evidence” with an unsolved 1984 rape and double murder. Sadly, it was a laboratory bungle. Even more sadly, it wasn’t the only one.

Teenager Farah Jama was convicted on false DNA evidence in 2006 and wrongly imprisoned for three years for a “rape” he didn’t do and which probably didn’t happen at all.

Police (and media) pursued innocent CFA volunteer Ron Philpott for two years over the fatal Murrindindi “Black Saturday” fire of 2009 before finally conceding the real culprit was faulty power lines, a conclusion that authorities and vested corporate interests found unpalatable.

Then there’s the one that got away. Farmer’s wife Kaye King was found upside down in a farm waste sump near Shepparton in 1991. Local cops persuaded homicide detectives there was “nothing to see here”. When a pathologist discreetly pointed out bruises on the victim’s neck that looked like thumb prints, a detective snapped: “We’re not the Almost-Homicide squad.”

These cautionary tales go on and on. Perhaps police and justice ministers nationwide should commission a documentary film, a sort of dirty dozen of dumb police work, and ensure it’s shown to every recruit and detective training intake. And every new magistrate and prosecutor. And young reporters.

Why? Because those who ignore history are condemned to repeat it.