Andrew Rule: Could Tapp murders cold-case killer be hiding in plain sight?

A DNA bungle and disrupted crime scene have left the Tapp murders almost forgotten but could intriguing evidence link a charming deviate to one of Victoria’s worst unsolved cases?

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Early every day a tall man with a tiny tan dog steps out of an anonymous modern house on to an empty street and heads around the block or down to the riverbank.

He is broad-shouldered under the navy windcheater and looks active for his age, which is mid-70s. On even the chilliest morning this week, he wore shorts — a uniform among men who spend their autumn years playing golf here in the retirement belt.

The shorts tell the world that the wearer doesn’t have to dress for work anymore. This particular day, in fact, he’s set to play golf as soon as he has walks the dog. And he still fancies tennis, the game he loved when his private court drew friends and neighbours to his trophy home in the Dandenongs, far from here.

That life is long gone. He hasn’t worked in his profession since the late 1990s, when his dark past and secret vices finally caught him.

That was when he was convicted of the one charge that stuck among many accusations of child sexual assault leveled by people who had once thought him a friend.

In truth, he was no one’s friend. He was a charming narcissist and deviate who for two decades parlayed his trusted position and good looks to prey on girls ranging from four years old to young adults. One was his daughter.

Even before he was convicted, he was in disgrace. He was stripped of the licence to practise his profession. His wife left him, changed her name and remarried.

Two of his three children, damaged by the secret horrors of their upbringing, would become drug addicts. All of them believe he is capable of almost anything.

One of them told this reporter four years ago that his father should be prime suspect for one of Australia’s worst cold cases — the murder of Margaret Tapp and her nine-year-old daughter Seana in their Ferntree Gully house on August 7, 1984.

It was a crime comparable with the Easey Street murders in Collingwood seven years earlier, yet it never received the same amount of attention.

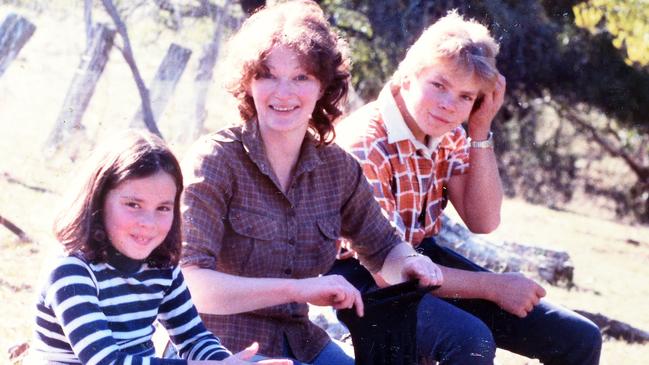

Margaret Tapp, then 35, was the life of the party, a nurse loved by many and admired by some but regarded by workmates at the Angliss Hospital in Ferntree Gully as a magnet for men and trouble.

“Marg” was generous, gregarious and intelligent — she studied law part-time, as well as nursing — but her best friend from that time says some other nurses saw her as a “homewrecker”.

She lived in the house at 13 Kelvin Drive that one of her lovers, Dr John Bradtke, had bought her before his accidental death in early 1983. But at least seven other men, including a prominent anaesthetist and a urologist, had also been infatuated with her.

When Margaret and Seana were found strangled in their home, the homicide squad’s problem was not that it had no suspects but that it had too many.

Margaret’s recent circle of acquaintances included fellow Monash law students and an instructor who was teaching her to drive a truck — because, typically, she wanted to help a farmer friend at harvest time.

There was an unsavoury family living in the same street, one of them a serious sex offender, and there were knockabout council workers who had helped Margaret’s brother move furniture into the house. Another outlier was a regular but unwelcome visitor, a former policeman well-known to Margaret’s parents.

The key clue was that it appeared to be sexually motivated rather than a “burglary gone wrong” or a crime of jealousy or revenge. Margaret’s body showed no sign of sexual activity — but semen was found on Seana’s night dress.

The killer was obviously a pedophile capable of violence to cover his tracks, implying he was known to his victims. Their bodies had been found tucked neatly in separate beds with the covers pulled up to hide the ligature marks on their necks.

The only real clue to the killer’s identity were unidentified footprints left in the house by someone wearing Volley tennis shoes. The distinctive zig-zag ripple soles had left clear marks of what looked like the red dust from an en tout cas tennis court. No one with a legitimate reason to be in the house wore Volleys.

After an initial flurry of activity, the Tapp case stalled. The homicide squad filed it alongside another baffling local murder — the killing of another single mother in a nearby suburb earlier that year. That was Nanette Ellis, stabbed to death at home at Boronia in February.

Nanette Ellis’s murder got more coverage than the Tapp case because Margaret’s relatives were reluctant to risk dragging her name through the mud to attract publicity in the hope of flushing out suspects. In the weeks following the double murder, it attracted only a handful of newspaper stories because no one had anything new to say.

The case would become almost forgotten by the public for another 20 years, until a story leaked that the former policeman known to be a visitor at 13 Kelvin Drive had been allowed into the crime scene to retrieve books or letters. A crime reporter who had worked in Melbourne before moving interstate had heard this first-hand from a close relative, a detective disgusted that the force had failed the Tapps so badly.

For years, it seemed, the retired policeman should have been a person of interest. Margaret’s older sister told investigators from the start that Margaret had privately complained to her that the man was creepy and unnerved her by dropping in unexpectedly.

But if the ex-policeman seemed somehow beyond stringent investigation, he was not the only one: others who’d had contact with Margaret had also apparently slipped through the net.

One of them was the tennis-playing socialite who would later be exposed as a ruthless sexual predator. In 1984 he had enough social and professional clout to seem beyond reproach. Only the children he molested knew otherwise, although some among the women who enjoyed canapes and champagne at his parties preferred not to see him alone in his professional capacity.

Good-looking and successful, he seemed to have it all: big income, luxury house, sleek European cars and overseas skiing holidays. He was slick but eventually his sins caught up.

Evidence was given that he molested children at his home, at their homes and on holidays. Some of them were his daughter’s school friends.

A new generation of police appear no closer to unmasking the Tapp killer than their predecessors were nearly 38 years ago. One problem, it seems, is that the semen sample used for DNA comparison has been totally compromised because of an appalling laboratory bungle in 2008.

That year, detectives were so confident they had a DNA “hit” they leaked a story that a serving prisoner, Russell Gesah, would be charged with the murders. When it turned out days later that Gesah had a watertight alibi, embarrassed checks exposed the laboratory debacle.

Meanwhile, Seana’s older brother Justin had moved to England, trying to escape the inescapable. Only 14 when the murders were committed, he was tortured by the thought that if he’d been home that night, rather than staying with his grandparents, it wouldn’t have happened.

The anguished schoolboy became a damaged adult who hit the bottle to blot out the nightmares. He died alone at 44 in a dirty flat in a Buckinghamshire town in 2014 after several suicide attempts.

His body had decomposed so badly before being discovered that the coroner could pinpoint no precise cause of death. But it’s clear that Justin Tapp had become the killer’s third victim.

For investigators, little has changed since Justin’s death. No one except a handful of police know if the disgraced professional has been “cleared” in the four years since the Sunday Herald Sun revealed the damning circumstantial case against him. The problem, of course, is that after the Gesah bungle, no DNA test linked to the case would stand scrutiny in a criminal trial.

The evidence is intriguing. The suspect often visited Angliss Hospital as part of his work and would most likely have met Margaret there. The Tapps were murdered on a Tuesday night — the same night the suspect played tennis in a winter competition at Ferny Creek, a short drive from Kelvin Drive. It would be easy to visit the friendly nurse with the young daughter after tennis.

As for the Volley tennis shoes, that’s what he always wore to play — in size 11, his son says. And the Ferny Creek courts were en tout cas, which would explain the clear footprints at the crime scene.

Now, in the town where the disgraced man lives alone with his cute little dog, most locals know something isn’t right about him.

By chance or design, he bought a house between two busy primary schools and a skate park where teenagers hang out. A couple with a young daughter live next door.

During term time, he walks slowly past the schools with the friendly dog, as if he likes watching children. A lot of parents and grandparents heed the rumours and warn kids not to walk past his house or talk to him.

In fact, some older men around town make sure they walk their own dogs at the same time so they can watch the watcher. Just in case.