Andrew Rule: No answers 30 years on from Karmein Chan tragedy

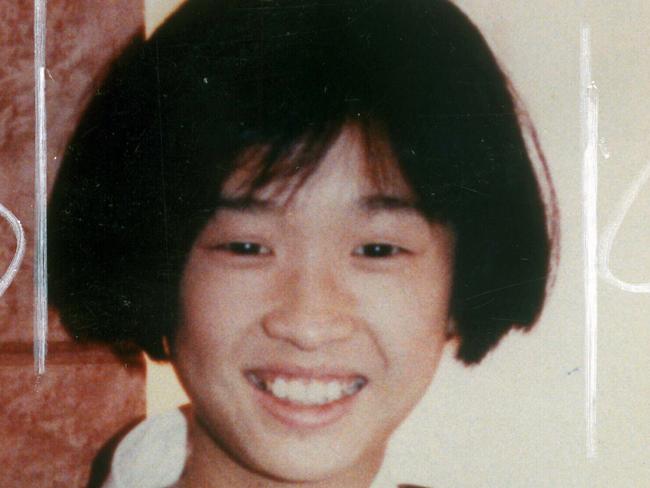

A serial child abductor, a triad execution or a kidnap for ransom? Thirty years on, a cunning killer and police missteps have kept Karmein Chan’s death a mystery.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It is 30 years this week since a team of grim-faced police and forensic experts gently lifted the remains of Karmein Chan from a shallow grave in wasteland beside Edgars Creek in Thomastown.

The teenager had been abducted from her family’s home in Templestowe almost exactly a year before. With every week that she’d been missing, the appalling mystery had grown more chilling.

The horror of the missing girl gripped everyone from the premier’s office to the prison exercise yard. Police were besieged with tips, mostly well-meaning but some deluded or malicious.

People looked sideways at workmates, neighbours and ex-husbands, wondering who might be capable of shooting a 13-year-old girl in the head in cold blood.

Investigators racked their brains for every angle, especially the likelihood the abductor was a known offender.

The Spectrum task force was set up soon after to examine possible links with at least three crimes over the preceding 44 months: the abduction of two other schoolgirls, Sharon in Ringwood and Nicola in Canterbury, and a similarly terrifying home invasion at Lower Plenty involving an 11-year-old girl.

The Lower Plenty child was assaulted but not abducted. Sharon and Nicola were released, traumatised but physically unharmed, after long hours locked up with the abductor, whereas Karmein had vanished.

But the similarities seemed clear: in each case a calm masked and gloved man armed with a knife and a handgun had broken into a family home at night, quite prepared to menace and immobilise parents or siblings to get to his target.

Nothing he did seemed random. It was as if he’d planned each attack for weeks or months. The families didn’t know him but he certainly knew them, which implies he’d done covert surveillance. He was so unnervingly cool he even took a break to eat a snack during one prolonged home invasion.

The survivors could give vague pointers to the man’s description: he was of middle height and had a slight paunch and reddish brown hair.

He had a knockabout “Aussie” worker’s accent, but spoke quietly and used bland expressions like “bozo”, “worry wart” and “missy”. He pretended to talk to unheard people as if to convince his blindfolded victims he wasn’t alone. This showed he liked to lay false trails.

The pressure on police was enormous. Any small miscalculation could have lasting consequences.

It was inevitable that decisions made in the glare of publicity pushed the investigation down paths still obvious three decades later.

The abductor was “cool and cruel,” a policeman told reporters in a throwaway remark after the first home invasion in August 1987. That extra word created the lingering misconception that the unknown man must look “cruel” because that’s the word that made the headlines.

“Mr Cool” or “Mr Calm” would have been a better tag because, in reality, the offender was polite and quietly spoken. The circumstances were terrifying but his demeanour was pitched to persuade scared victims he wouldn’t hurt them if they co-operated.

This was a Mr Cool, right down to washing his victims and getting rid of their clothes to remove traces of forensic evidence. But the catchy Mr Cruel label took hold and has helped the abductor hide in plain sight for 30 years.

While the public imagined an obvious monster, this mild-mannered everyman could blend into any suburban scene — walking a dog, mowing a lawn or holding a lolly pop sign.

His methodical modus operandi suggested he might be a serving or retired emergency service worker: if not a policeman then maybe an ambulance officer, fireman, prison officer or ex-military serviceman.

Unfortunate as the “Cruel” label was, it wasn’t the worst mistake.

It might be that police’s worst own goal was a basic error that pushed the investigation off course so much it would ultimately mislead FBI experts given dud information on which to profile the offender.

Embarrassed investigators have never actually admitted wasting FBI time, let alone misleading the public, repeating the error until it became accepted as “fact”, which it sometimes still is.

This error, only grudgingly acknowledged in recent years, was the mistaken assertion that the home invasion and three abductions had happened during school holidays.

They didn’t. In fact, when Nicola was released in Kew after her 50-hour ordeal in the first week of July, 1990, newspapers actually carried reports of her classmates singing “Happy Birthday” for her at school.

Two of the other three crimes happened on weekends, making it irrelevant whether it was school holidays or not — and in any case, one of those weekends was mid-term.

The abduction of Sharon at Ringwood happened on the morning after Boxing Day, 1988, when virtually everyone was on holiday anyway, not just teachers and pupils.

The “school holidays” angle was a furphy but it took root, slanting police and public efforts towards looking at thousands of teachers or other males connected with schools.

The possibly random fact that Karmein Chan and Nicola were both enrolled at Presbyterian Ladies College encouraged baffled police to guess there must be a link between that school and the abductor. In the absence of a real lead, investigators seized on an unremarkable coincidence.

Not everyone agreed on this. Some detectives and reporters still wonder, if Karmein had attended the local high school, would investigators have concentrated harder on very different angles, such as the murder possibly being punishment by international “triad” gangsters extorting Asian-owned businesses? Or a kidnap-for-ransom gone wrong?

In the weeks after Karmein’s abduction, any male who had worked at PLC or had contact with its students were visited by detectives looking for incriminating evidence: guns, knives, balaclavas and child pornography.

One of many men the police visited was a longtime Telstra employee (and school chess coach) named Christian Bennett. Mr Bennett had coached PLC students at chess for five years in the 1980s. He was one of dozens of former staff members, employees, volunteers and parents.

The detectives measured his feet, leaving the impression they’d found unidentified footprints at a crime scene. He thinks they lost interest in him as a potential suspect after noting his large foot size.

But Christian Bennett never lost interest in the police, reviewing the mammoth investigation with all the zealotry of countless DIY sleuths who comb the internet and public records for data to build theories that range from crackpot fantasies to clever deductions.

Like all single-issue enthusiasts verging on the obsessive, these armchair detectives tend to be ignored by police and reporters, who sometimes interpret their zeal as a sign of a nuisance — if not someone who should be on a watch list as a potential offender.

Few amateur sleuths have the intellect, energy and writing skill of the late Michelle McNamara, the “citizen detective” who coined the name “the Golden State Killer” for the mystery serial killer who turned out to be Joseph James DeAngelo, the former policeman ultimately arrested in 2018 through brilliant use of genealogy DNA databases.

McNamara’s posthumously published book, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, grew into a riveting documentary about DeAngelo’s crimes.

Christian Bennett is no Michelle McNamara. His tendency to compile exhaustively detailed dossiers can obscure the kernel of common sense and sharp observation in them. But buried in the reams of material he has sent to bemused police and reporters over the years, he hammers some consistent themes.

One is the school holiday mistake outlined above, a point proven beyond reasonable doubt by cross-checking contemporary media reports and education gazettes.

But perhaps the strongest observation is that each of the four attacks (and the subsequent release points of the abducted girls) seem to have occurred close to high-voltage power lines or substations.

Once mapped, this seems more pattern than coincidence. It leaves an inference that the wanted man was familiar with the metropolitan electricity system, something Spectrum task force police no doubt looked at while interviewing some 27,000 men, checking 30,000 houses and 10,000 “tips” over four years.

Crime behaviour experts know that offenders nearly always go to places they know either to commit crimes or to get rid of evidence, especially a body.

Time after time, killers dump bodies in places they have been before, and robbers plan escape routes or hide loot or weapons in familiar territory. It is human nature to behave that way.

If the abductor is still alive, he’s surely the only person who knows he is the man who was dubbed “Mr Cruel” nearly three years before Karmein Chan was kidnapped and shot three times in the head.

But is that abductor behind all four crimes? Or, in a case full of false leads and red herrings, is Karmein Chan’s murder the biggest one of all?

Crime reporter Keith Moor, who followed the case for this newspaper from the start, knows some police who still privately question the assumption that the Chan killer was the child abductor behind the three earlier abductions.

In truth, police were obliged to treat the Chan killing as one of the “Mr Cruel” abductions because there are simply not many cases where a masked man with a handgun abducts teenage girls in a particular area of Melbourne, Moor says.

Karmein’s parents, Phyllis and John Chan, never once said anything that indicated Asian crime gangsters might be involved. In fact, Phyllis believed her feisty girl could have provoked the “peaceful” offender into murder by snatching his mask.

Once that happened, the theory goes, the abductor would kill rather than risk jail for life.

It is true that not many child abductors execute children with head shots like a hit man. Then again, not many child abductors carry a pistol.