Andrew Rule: A criminal, looking to clear the slate before his death, turns to a detective and asks: ‘Do you want to know who Mr Cruel is?’

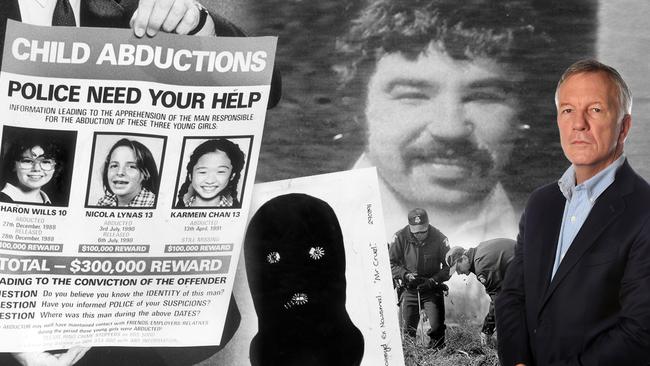

A stunning claim from a dying criminal may provide the best lead yet to identifying the child-abducting murderer known as Mr Cruel.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

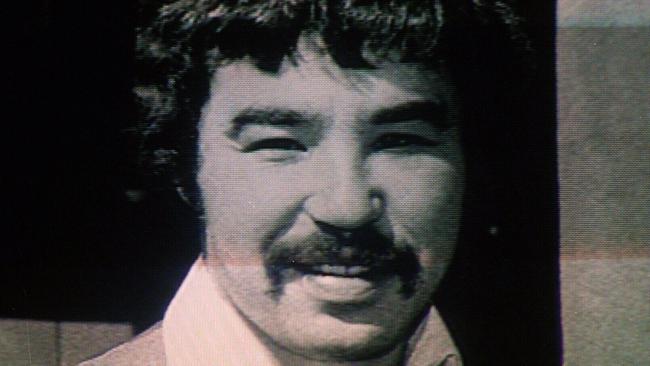

Normie Lee fought the law once too often. The bent businessman with the dodgy dim sim factory bankrolled by bank robbery couldn’t quit the “takeaway” business and it got him killed.

A police bullet ended it all when he and two other masked men tried on a million-dollar heist at Melbourne Airport in July, 1992.

Lee “died game”, gun in hand. He’s remembered as criminal royalty along with his mate, Great Bookie robber Raymond Patrick Bennett, and the legendary Russell “Mad Dog” Cox.

But did he die with a terrible secret, even by criminal standards?

This was the man who sat stony silent when interrogated over the missing millions from the Great Bookie Robbery in 1976. The man who wouldn’t hand over the key to his office safe even when police produced a blowtorch. He watched the blue flame cut it open, poker faced, even though nothing was inside.

So cool, so smart, so tough. But the robber with a business brain was an enigma. Which makes the story one of his contemporaries told a detective all the more intriguing.

It might be the best lead yet on “Mr Cruel”.

The story starts with three arrests 33 years ago this month, in April 1989. The drug squad grabs two people trafficking amphetamines in Noble Park and then arrests their boss, a “good crook” named Alf Gay, at Bittern.

Gay is in his 50s then. He’s reputedly one of those who pulled the fabled MSS robbery in South Melbourne in 1970, when bandits disguised as security guards calmly wheeled 48 cases of cash out of the security depot into a ute. It was the entire Ford factory payroll, a staggering sting.

In 1989, Alf Gay still runs with a heavy crew. But he’s grateful that the detective running his case, a well-known former homicide investigator, doesn’t oppose bail for him and his co-offenders. The detective treats them fairly. His men don’t rob the crook’s family, the way some rogue cops did in the 1980s.

Years after Gay leaves jail, the detective visits him to discuss a case. After an amicable chat about safe cracking, he’s leaving when Gay follows him to his car and calls him back. He has something to tell him.

He says he has cancer, wants to clear the slate before he dies. Then he floors the cop with a question.

“Do you want to know who Mr Cruel is?”

Gay swears that his longtime friend Normie Lee, one of the bookie robbery crew, is the masked man who abducted at least three schoolgirls and assaulted a fourth.

The thing about Lee the streetfighter and gunman, says the old robber, is that he had a schoolgirl fetish, even a collection of school dresses. So when he’d told Gay he killed Karmein Chan, it fit.

Gay says he once visited the house where Lee held at least one of the abducted girls. Days later, the detective drives him to Eltham, past where Karmein’s parents had their restaurant when she was abducted in April 1991.

They turn down a street near the Eltham Hotel where Gay used to meet Lee to discuss “business” nearly 20 years earlier. Gay looks for a house on the south side of the street.

But things have changed since the 1980s. The house he’s looking for seems to have been demolished along with others. New buildings cover the most likely locations.

He tells the detective the house had a garage converted into a secure “granny flat” with a bed and adjacent toilet, basin and shower.

He says it had a chunky pine couch and other details matching sketchy information police got from the two girls who were released after being blindfolded during their ordeals.

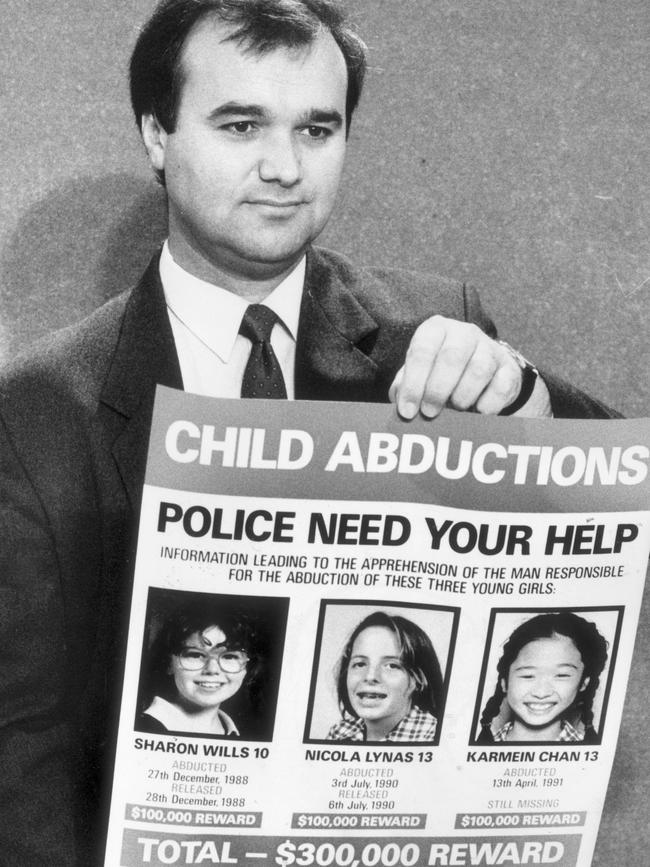

By this time, the Spectrum task force had long been disbanded after nearly three years of footslogging following Karmein Chan’s abduction.

Teams of plain clothes police doorknocked some 30,000 houses, looking for one with the basic layout the girls memorised. They also eliminated 27,000 men, clearing a barrage of tips from the public.

This huge effort led to the charging of some 70 paedophiles — but not Mr Cruel.

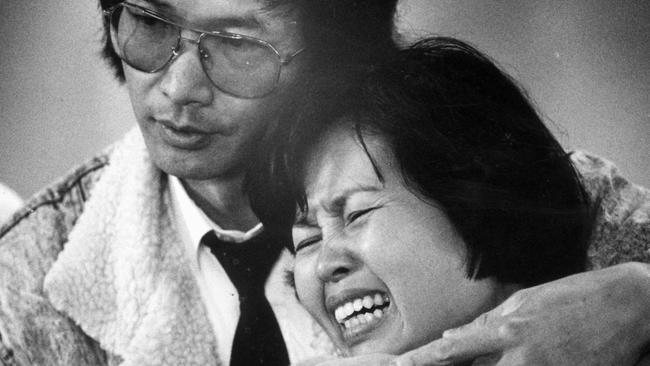

Naturally, the detective passed the information to police handling the huge Spectrum file. Naming a dead man as the offender didn’t spark much enthusiasm. A senior officer showed Karmein’s mother a photograph of Lee. When she said she didn’t recognise him, nothing more was done.

The detective was disappointed at the dead end but said nothing publicly until this week, when he told this newspaper. We asked archive expert Sue McBeth to search for documentary evidence linking Lee to Eltham. In 24 hours she made a breakthrough: Lee’s will (under the name “Leon Norman Lee”) revealed he owned a house in Napoleon St, Eltham, right through the 1980s.

Napoleon St is one of few streets that fits Gay’s description. The position of the former Lee house on the south side matches the position Gay showed the detective.

The idea that Mr Cruel operated from Eltham fits perfectly with the abduction of Sharon Wills from Ringwood East in late 1988. Also, Napoleon St is walking distance from the Chans’ restaurant and a short drive from where the Chans lived in Templestowe — and close to where Mr Cruel assaulted a girl at home in Lower Plenty in August, 1987. And it’s only 15 km from where Nicola Lynas was abducted in Canterbury.

Plot it on a map and there it is, the Mr Cruel triangle: Eltham at the apex in the north, Canterbury the west corner and Ringwood the east corner. Inside the triangle is the Lower Plenty house (where Mr Cruel assaulted an 11-year-old) and the Chan home in Lower Templestowe.

Of the four known Mr Cruel offences, none was committed further than 20 km or 20 minutes by car from Eltham. Two attacks were only 10 minutes from Eltham.

The one apparent “outlier” is that Karmein Chan’s body was buried near Edgars Creek in Thomastown. But, in fact, that also fits the Normie Lee scenario.

Firstly, the gravesite is only 11 km from Eltham. And it is in the right direction.

Police know that offenders invariably bury bodies (or loot) somewhere they know. Karmein’s remains were found next to Mahoney’s Rd. It’s almost certain Lee used Mahoney’s Rd to go from Eltham to his usual haunts around Flemington, where he owned property and a business.

If he killed Karmein Chan, as he’d admitted to Gay, the Edgars Creek wasteland would seem far enough from both his Eltham and Flemington bases but also an easy spot to bury a body in a hurry after what was almost certainly an unplanned murder.

Phyllis Chan has always believed that her feisty daughter must have defied the abductor and pulled off his mask, prompting him to kill her. This tallies with the fact Mr Cruel had warned victims his freedom was worth more than their life.

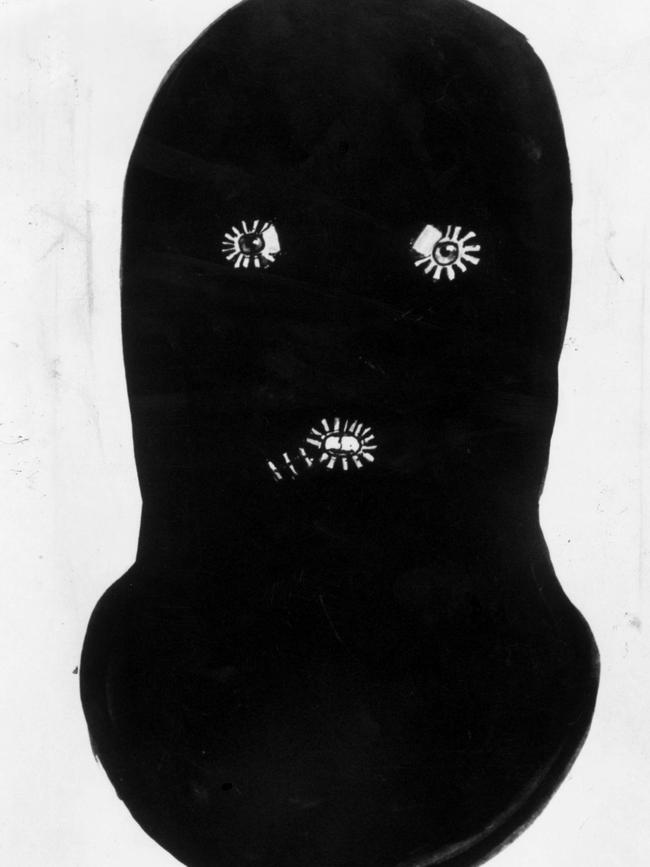

Anyone could make that chilling threat but a hardened armed robber — one whose industrial meat mincer had reputedly ground up bodies — would actually go through with it. Mr Cruel was a calculating criminal who used a handgun, mask and gloves and was cold-bloodedly thorough about destroying evidence.

The psychological profilers’ catch-all profile of the child abductor might have nudged investigators towards looking for an outwardly harmless, mild-mannered man, such as the former academic (and serious sex offender) who was for years at the top of a short list of seven suspects.

Sadly, profilers are just as often wrong as right. In the real world, the sort of offender who kills a witness in cold blood seems more likely to be a rogue policeman, ex-military man — or a violent career criminal.

It’s not criticising the Spectrum task force to say that its biggest problem in 1991, in looking for literally one man in a million, was to cut the field to a workable size.

Unfortunately, circumstances led police to discount the area where Mr Cruel had actually struck — and where he probably lived.

How could such a huge investigation lose its bearings?

Here’s how. The two abducted girls released by Mr Cruel each spoke of hearing aircraft, as opposed to trains or traffic. In the absence of other clues, the aircraft became the strongest angle apart from sketchy descriptions of the bedroom and bathroom where the blindfolded girls had been imprisoned.

Nicola Lynas, the older of the two, was an impressive witness whose evidence persuaded investigators that the abductor’s house must be close to Melbourne Airport.

Nicola had counted the number of jets heard in a given hour — and told detectives she could tell they were descending. Understandably, this convinced them they were hunting for a house near the airport.

What probably sealed the deal to concentrate well west of where the victims were actually taken was the fact Karmein’s remains had been found at Thomastown.

The combined effect of the Thomastown gravesite and the airport’s location at Tullamarine seemingly skewed the decision to concentrate west of the Mr Cruel triangle. It seems the search area was inside the ring of “locator” beacons that pilots use to mark the beginning of their final descent exactly 10 nautical miles from the airport.

The problem with that was that Eltham and other suburbs in the Mr Cruel triangle lie outside that arbitrary circle, and so houses there were never searched. This was despite the practical reality that much of the air traffic on one of the world’s busiest routes approached from the northeast then turned west towards Melbourne’s two big airports … passing right over Eltham.

The “locators” are 10 nautical miles from Melbourne Airport, a distance of nearly 19 km. What police might not have realised is that original locators set up 10 nautical miles from the old Essendon Airport were (and are) still used by big jets, not just by the smaller aircraft that routinely use Essendon. One such locator is tagged MONTY on aviation maps because it’s at Montmorency, right next to Eltham.

Why this matters is that pilots landing airliners on the northern runway at Tullamarine into a northerly wind regularly bypassed the regular locator at Epping, instead flying low over Eltham and turning west at the old MONTY site to fly directly over Essendon Airport, a clear landmark from which they could easily do a “visual” (non-instrument) landing at Tullamarine.

This much-used detour explains why Eltham area residents often hear big jets as well as the smaller ones that regularly use Essendon.

Thirty years ago, they heard them even more because jets were allowed to fly lower for longer — and many jet engines then were louder than they are now.

The decibel level from an old-style jet flying at 3000ft in 1990 was loud enough to make conversation difficult. At night, cool air pulls the sound downwards and makes aircraft seem even louder. All of which meant that terrified, blindfolded girls below would hear them clearly if they were being held in Eltham.

It seems likely that pilots’ continuing use of the old Essendon locators led the task force astray. Proof is that they painstakingly checked tens of thousands of houses much closer to Tullamarine than to Eltham — and found nothing.

As for Norman Leung Lee, the ruthless robber with the schoolgirl fetish, after he was killed in July 1992 there were no more Mr Cruel attacks. That, of course, could be coincidence.

Lee apparently sold the Napoleon St house by 1990. But the detective behind this story believes such a devious crook would have had another secret hideaway east of Melbourne, owned or rented in someone else’s name.

Lee died owning side-by-side buildings in Racecourse Rd, Flemington. When his de facto wife sold them later, the new owners found a secret tunnel leading from a cupboard to the back lane.

In the tunnel was a package. In the package was $15,000 cash. Cunning to the end, Normie Lee had plotted a perfect getaway plan — but he couldn’t dodge the bullet that sealed his secrets in the grave.