Mitchell Toy: Twenty years since Australia’s waterfront fight

IT HAS been 20 years since 1400 workers were sacked on Australian ports, sparking a battle between bosses and unions that reshaped workplaces across Australia forever.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News . Followed categories will be added to My News.

JUST after 11pm on a crisp night in 1998, vans and dinghies converged on Australian ports.

As dock workers were completing their shifts, some high above the ground in waterside cranes, dozens of security guards systematically closed the workplace down.

Some workers reported guards dressed in black wearing balaclavas and many saw rottweilers and German Shepherds.

Soon it became clear what was happening.

Patrick Stevedores, under chief Chris Corrigan, had set into action the boldest workplace upheaval in living memory — 1400 workers, members of the Maritime Union of Australia, were sacked.

MORE MITCHELL TOY: GREAT STORIES OF MELBOURNE

THE 12 TRAIN COMMUTERS YOU NEED TO AVOID

They were locked out of port sites and replaced by non-union workers trained secretly in Dubai.

The union picketed and the Howard Government backed Corrigan.

The ensuing standoff some 20 years ago gave rise to one of the most significant industrial reforms in Australia’s history.

PROBLEMS ON THE DOCKS

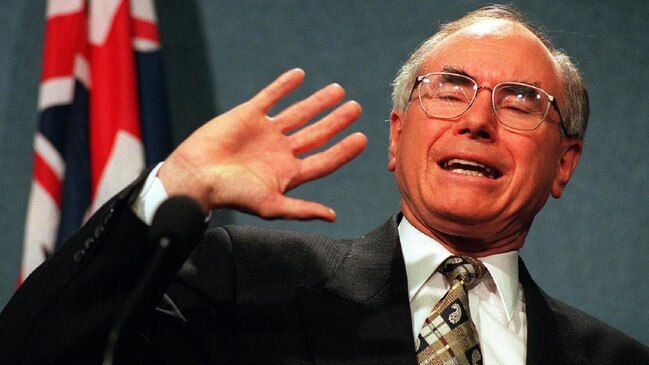

When John Howard won the 1996 election, he had a mandate for industrial reform.

A Federal Government study of the efficiency of Australian ports painted a dire picture.

The cost of services and infrastructure use in Australia was, on average, three times greater than at ports overseas.

And although importers and exporters paid a premium to move goods through Australian ports, productivity wasn’t as good as overseas and the labour of dock workers was often unreliable.

Then there was the MUA.

Union officials were controlling almost everything to do with day to day operations.

They decided which workers took what jobs, when the worked and for how long.

They even controlled efficiency by deciding how many containers could move per hour.

It was clear to Chris Corrigan that something had to be done.

Not only did he believe that the MUA was stuck in an outmoded way of working and was hurting productivity, but there were rife accusations of criminality and bullying.

And most importantly it was near impossible to work on a dock site without first carrying an MUA membership card.

The true cost of the union’s underperformance, Corrigan argued, was being paid for by Australian consumers.

But the action that came next was truly extraordinary, and would bring to a head years of struggle and animosity between Corrigan and the MUA under then-secretary John Coombs.

LOCKED OUT

Preceding the mass sacking, Patrick had undergone a shuffling restructure of its business arms to make it easier to dismiss the workforce and find alternative labour.

The Howard Government had also started legislating to limit the power of unions such as the MUA.

It meant, remarkably, that a union previously boasting an iron grip over almost every part of Patrick’s waterfront operations, could be sacked with no notice or warning on April 7 1998.

The fallout was predictably spectacular.

Union workers, their friends and supporters formed picket lines, the biggest of which was at Melbourne’s Webb Dock.

The picket was manned day and night for weeks with a village of sausage sizzles, live music and kids in MUA garb, chanting the now famous cry, “MUA, here to stay”.

Patrick struggled to bus in new workers and trucks of shipping containers as MUA supporters linked arms and clashed with police.

Images of children crying as officers dragged protesters from the line were broadcast around the country.

But still the company, and Workplace Minister Peter Reith, didn’t budge.

RESOLUTION

As the picket carrier on, court action started against Patrick to try and reverse the sacking.

The case went before the Federal Court where it was found the company intentionally rearranged its business arms to dismiss its workforce.

There were also concerns the company sacked the workers for being members of the MUA.

The court ruled in the union’s favour, met with jubilation at the picket line.

The decision led to a new agreement between the company and the MUA involving many voluntary redundancies, changes to rostering, casualisation and productivity targets.

Although the union won in court, the outcome was nothing short of radical workplace reform on the waterfront that saw many objectives of the Howard Government achieved, and the course of industrial relations in Australia changed forever.