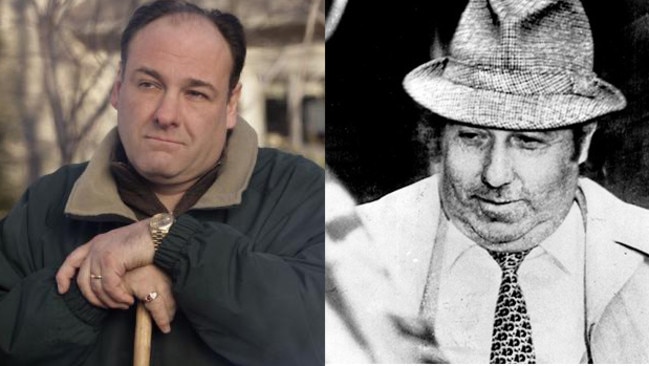

Australian mafia’s ‘Mr Fix It’ Robert Trimbole a victim of crime after death like Sopranos star James Gandolfini

A ROLEX stolen from the wrist of dying Sopranos star James Gandolfini pales into insignificance when compared with what happened to an Australian Calabrian mafia heavy writes Keith Moor.

True Crime Scene

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime Scene. Followed categories will be added to My News.

TO paraphrase Paul Hogan in Crocodile Dundee, you call nicking a watch off a fake Godfather a theft?

Stealing the suit off the body of a real mafia Don — that’s a theft.

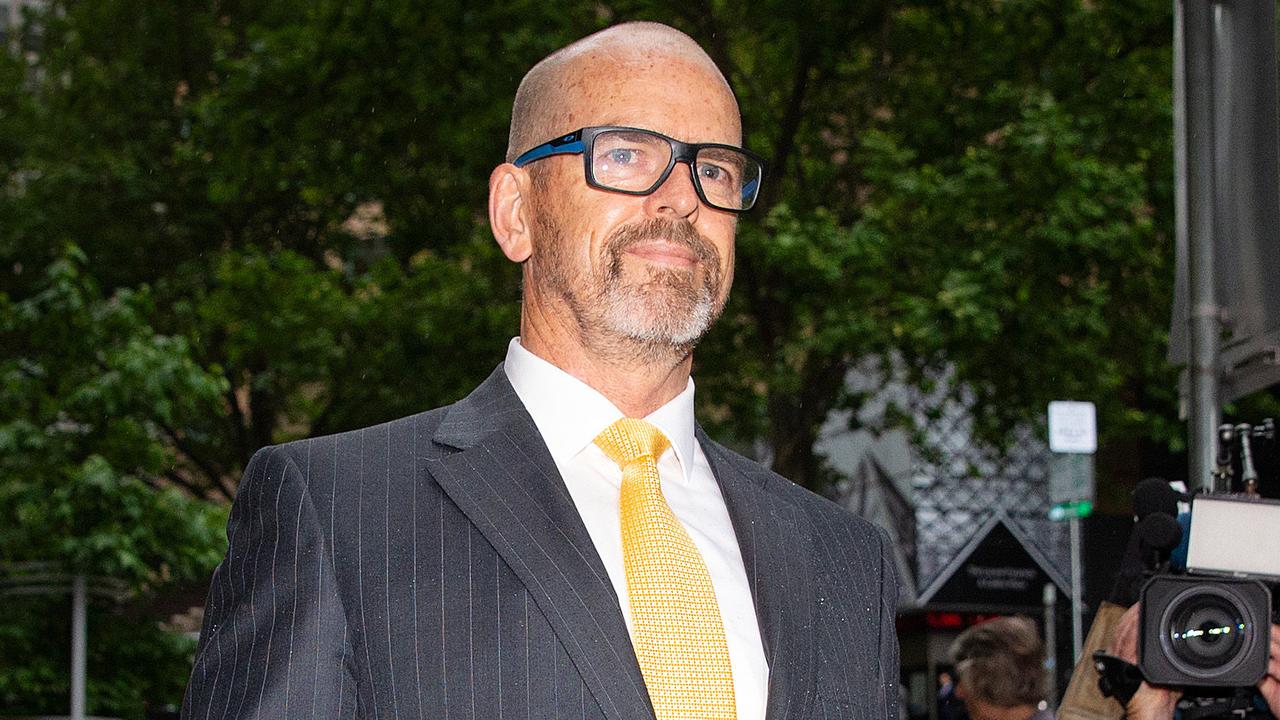

News that a paramedic this week appeared in an Italian court charged with stealing a Rolex from the wrist of dying Sopranos star James Gandolfini pales into insignificance when compared with what happened to Australian Calabrian mafia heavy Robert Trimbole.

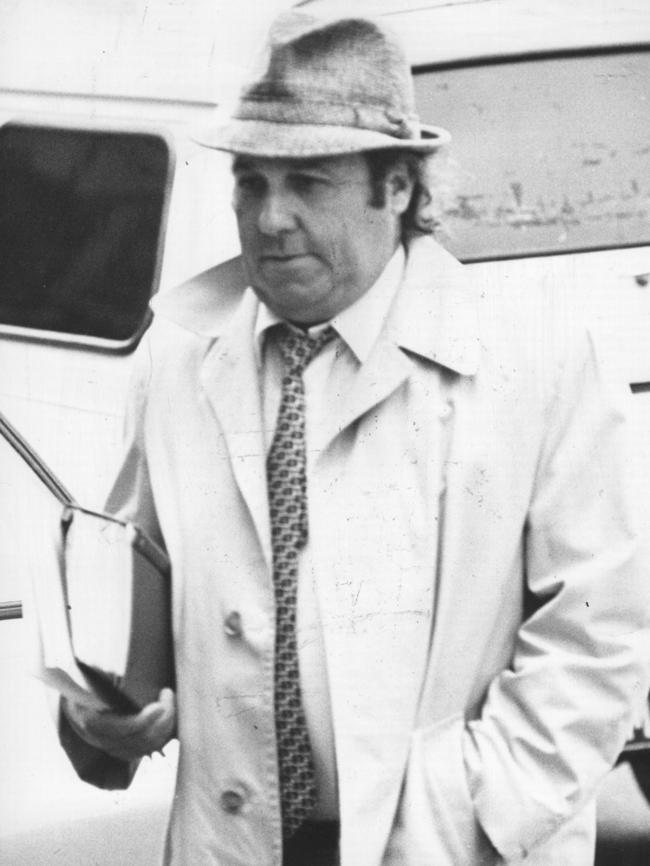

Trimbole died of natural causes in Spain in 1987 while on the run from Australian authorities.

An undertaker dressed the body in a pristine white suit.

That suit was nowhere to be seen when Australian journalists later talked Spanish mortuary workers into letting them view Trimbole’s body.

Those mortuary workers found it difficult to imagine that the now naked body being stared at by curious members of the media was that of Australia’s most wanted man.

The overweight, unkempt, uncultured Trimbole was always an unlikely looking crime boss.

Yet he was a powerful enough figure in Australia to fix murders, horseraces, early releases from prison and lighter-than-usual sentences for family members.

Not family members as in sons and daughters, but family as in La Famiglia.

Trimbole was known as the Mr Fix-It for Australia’s most notorious secret society.

The society is variously known as ‘Ndrangheta’ in Calabrian dialect; ‘L’Onorata Societa’ or the ‘Honoured Society’ by some Italians; ‘La Famiglia’ or the Family by others and simply the mafia by most in Australia.

Trimbole was a recognised master at compromising people of influence, winning over those in positions of power and generally getting onside with anybody that might one day help him and the Calabrian mafia.

“A great bloke” is the description many of his mates used to describe Aussie Bob.

Trimbole didn’t look so great lying on the mortuary slab of the Cemetaria Municipal in Villajoyosa, a few kilometres from the tiny Spanish town of Alfaz del Pi, which is where Trimbole hung his trademark pork-pie hat until his heart packed in on May 13, 1987.

Flies hovered round the bloated corpse in the hot and tiny room. A plastic shopping bag covered the brick chosen to support Trimbole’s head.

And ironically, Trimbole, an organiser of crime for most of his life, was himself a victim of crime after death in that someone stripped his body and robbed it of the expensive white suit in which the undertaker had dressed him.

That final ignominy angered Trimbole’s son Craig almost as much as the fact Australian newspapers ran photographs of the naked body of his father under headlines like “Finished at last”.

Others thought it fitting that Trimbole’s life of crime should end in humiliation, rather than glorification.

Trimbole’s family flew the body back to Australia.

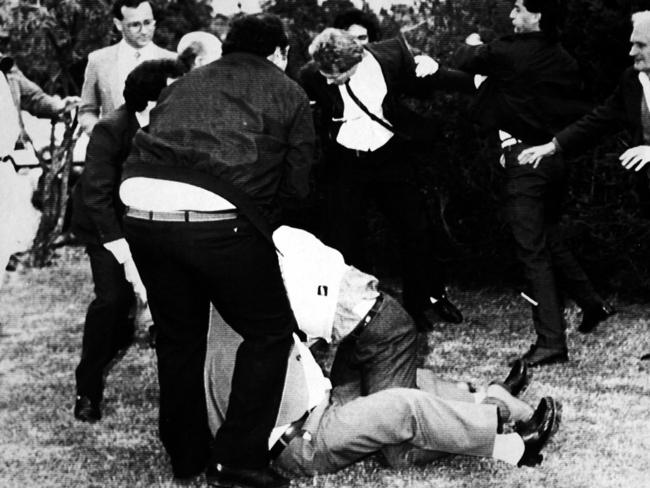

Despite attempts to keep the funeral a secret, the media was tipped off and journalists turned out in force for the Mass, held at St Benedict’s Church in the Sydney suburb of Smithfield on May 27, 1987.

Mourners were enraged at the sight of television cameras, reporters and photographers waiting outside the church and there were a number of ugly incidents.

One mourner brandished a wooden bat at journalists.

A Channel 7 camera crew was attacked and a man tried to rip the camera from the cameraman, who was kicked and punched repeatedly.

ABC crime reporter Max Uechtritz was set upon by three men and beaten to the ground.

Uechtritz gave almost as good as he got, but was overpowered and hurled into a hedge.

The then prime minister, Bob Hawke, got himself into strife with the Trimbole family by ringing

Uechtritz to congratulate him on the way he had fought his attackers at the funeral.

Hawke, like millions of Australians, had watched graphic television news footage of the funeral fracas, which included close-ups of Uechtritz’s bloodied face.

“I received a telephone call from Mr Hawke last night and he offered his support to me,” Uechtritz said in an interview broadcast the day after the Trimbole funeral.

“He told me he just wanted to let me know in person that he respected the way I defended myself and went to the aid of the newspaper photographer.

“He half-jokingly asked me if I had done any boxing. I told him I hadn’t, but I had copped a lot worse playing rugby.”

Hawke’s call incensed Craig Trimbole and he chose to use the Sydney airwaves to vent his anger.

Craig rang John Laws’ talk-back show on 2GB and blasted Hawke for congratulating Uechtritz on his role in the brawl at his father’s funeral.

“I don’t think the Prime Minister of Australia should congratulate fighting and say it is OK,” he said on air.

“I think it is really wrong of a man who should run the country. I think he should be sympathetic as well to the family.”

In death, just as in life, Trimbole continued to be surrounded by controversy.