Inside Darren Weir’s stable taking on the world

TRAINER Darren Weir has sprawling purpose-built stables near Ballarat that is producing winners like no other. Andrew Rule takes us inside the facility to see what it takes to get a run in the Melbourne Cup.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News . Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE biggest horse-training enterprise in Australia, maybe the world, isn’t at Flemington or Randwick. It’s the place they call “the ’Rat”, where cockatoos squawk overhead and stray kangaroos can make “jump outs” interesting.

Ballarat has always had horse people, going back to local heroes such as Adam Lindsay Gordon and Tommy Corrigan.

WEIR LEADS PUSH FOR CLOSED BEACHES TO BE REOPENED AT WARRNAMBOOL

LAST-MINUTE BETTING GUIDE AND TIPS FOR DERBY DAY AT FLEMINGTON

But if anyone had been reckless enough to predict 20 years ago that the coldest training centre this side of Tasmania would become the “hottest” in the business, they would have been laughed at.

Then along came Darren Weir, the Mallee boy who dreamed big dreams. It’s hard to believe now that “Weiry” trained his first Melbourne winner only a year before scraping up the deposit to buy Forest Lodge stables next to Ballarat racecourse in 2001.

The farmer’s son-turned farrier and horse breaker had taken out his full trainer’s licence only four years earlier, in 1997. He landed his first winner at Avoca in 1995 as a humble owner-trainer working for Terry O’Sullivan at Stawell.

Forest Lodge was run down. Weir had nothing but a mortgage, a battered horse float and determination.

Two years after winning the Melbourne Cup with Prince of Penzance, the boy from Berriwillock is up there with any trainer, anywhere, any time. Apart from his huge Ballarat operation, he has a satellite stable at Warrnambool he calls “the beach” — and is building a specialised training farm at the former Three Bridges stud at Maldon.

In Australia, only the remarkable Chris Waller and the durable David Hayes are in the same league. Overseas, top American trainers such as Todd Pletcher and Bob Baffert and the Irish wizard Aidan O’Brien are rightly famous but they don’t train the numbers Weir, Waller and Hayes do.

Not that comparisons worry Weir. Not much does, bar his obsession with keeping more than 200 horses fit and happy, and juggling hundreds more on a waiting list longer than Melbourne Grammar’s.

It’s a long way from riding a rough pony and feeding pigs on the family farm on the plains near Swan Hill — but it’s still about working with animals.

As a boy, young Weir helped look after his dad’s pigs and hunting dogs. His late father, Roy, once kept a few slow trotters but the first horse Darren had much to do with was a rogue pony called “Sunny”.

“The pony got the better of me at first but I got the better of him eventually,” recalls Weir in a rare quiet moment the day after the Cox Plate meeting — where he trained two winners and got Humidor to within a long neck of the world champion Winx. This followed four city wins on Caulfield Cup day.

Racehorses have long pedigrees and often huge price tags but once they start work, they are all treated as equals: from Mallee maidens to Derby hopefuls, their sole mission is to gallop harder for longer. There are no short cuts to fitness at the Weir boot camp.

No wonder one racing writer calls it “Weir Town”.

Its internal lanes have street signs, mostly tributes to the gallopers that helped pay for it: She’s Archie, Skewiff and the rest.

By sunrise, the staff carpark has 20 vehicles in it, and more keep coming. This is apart from five big horse trucks and a fleet of expensive floats in Weir Racing livery parked next to the sprawling complex.

Weir trains 120 horses here, another 80 with his Warrnambool foreman Jarrod McLean and he has a small team of “project” horses at the new farm at Maldon, which is six months off completion.

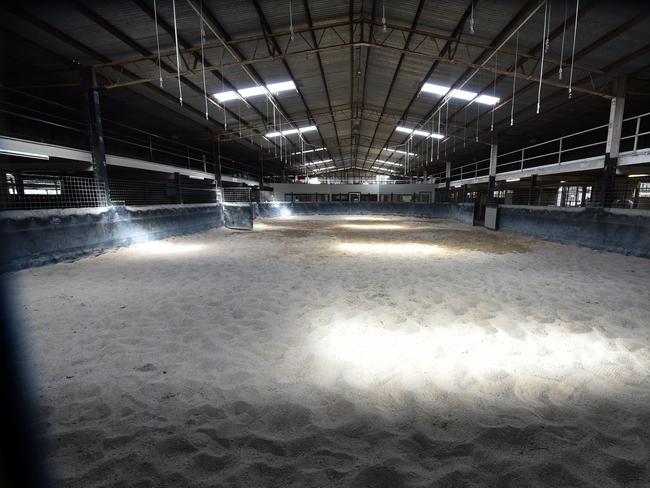

There, he has built another gently rising track covered in thousands of tonnes of deep sand to replicate West Australian training properties where Perth’s top trainers prepare horses with uncanny success.

But seven-day weeks and astonishing results are not enough for Weir, the constant builder. He is renovating the original homestead at Maldon to its former glory — not for himself but for lucky owners to stay and see their horses work in the countryside.

“Me, I’ll use the manager’s house,” says Weir. “I just like things that work.”

The 110 staff employed between the three properties includes a resident welder.

The day the Herald Sun visits, the full-time farrier is shaping and fitting racing “plates” to hoofs; a team of painters is painting looseboxes; a carpenter replacing old rails; a bricklayer rebuilding a wall.

The maintenance is as constant as the painstaking care each horse needs. A racing stable is part boarding school, part health resort, part hotel: it has to have full occupancy to stay in business.

Hundreds of horses are “on the books”, ready to fill gaps as they appear. When one leaves, another takes its place.

For at least six hours a morning, Forest Lodge is a production line. Horses to be worked on the track are saddled in a “stripping shed” under huge roof-mounted heaters that keep them warm when rugs come off. Then they go into one of two rotary “walkers” before each is ridden by one of a dozen track riders along a tree-lined lane to the racecourse.

Most Weir horses regularly gallop on Ballarat’s “secret weapon” — the 1400m straight uphill track that mimics the traditional Downs training “gallops” in England.

The steady rise makes them work hard but with little jarring and less risk of injury to vulnerable front legs.

“It’s speed and corners that break horses down,” says Weir.

Horses are like teenagers — exercise is good for them and makes them behave better. The combination of hard work and peaceful surrounds shows in the way they calmly walk home after galloping up the rise. Occasionally, a kangaroo spooks young horses but they soon get used to it.

MEANWHILE, back at Weir Town, other horses trot, canter or gallop on the bank of four motorised treadmills set up near the bigger of the two “walkers”. Treadmills are good for older horses or ones with leg problems because they can be worked “uphill” without a rider’s weight on an even, cushioned surface.

After working, some horses are swum in the circular pool with its central “island” — complete with movable bridge.

Then they are hosed, dried off and put in a loose box or day yard to be fed.

Each horse takes as much looking after as a hospital patient — which explains why about 40 stablehands work at the Ballarat yard, with more at Warrnambool and Maldon. Some veterans have worked for other big trainers or stud farms. Others are travellers with work visas — many from Britain and Ireland.

Weir’s top track rider — and increasingly successful race day jockey — is John Allen, who arrived from Ireland five years ago. Weir, the horseman’s horseman, says that Allen is the finest all-rounder he has seen.

Allen is as accomplished a flat jockey as he is over the jumps and a shrewd judge of ability and fitness. He won this year’s Grand Annual steeplechase — one of his seven winners at the Warrnambool carnival. On Caulfield Cup day, he won the $250,000 Ladbrokes Classic on Cliff’s Edge. At trackwork, says Weir, Allen can handle the roughest horse.

Around the stable, nicknames rule. John Allen is “Irish”. The boss is “Weiry” to everyone from strappers to millionaire owners. But the horses get the most colourful names. The sprinter that punters know as Gun Case is “Rifle” at home. Crafty Aquila is “Shoe”. Bloodlette is “Vampire”, naturally.

But Humidor, the one they’re barracking for on Tuesday, is “Humma” to his mates.