Andrew Rule: The fatal shore that claimed Prime Minister Harold Holt, 50 years on

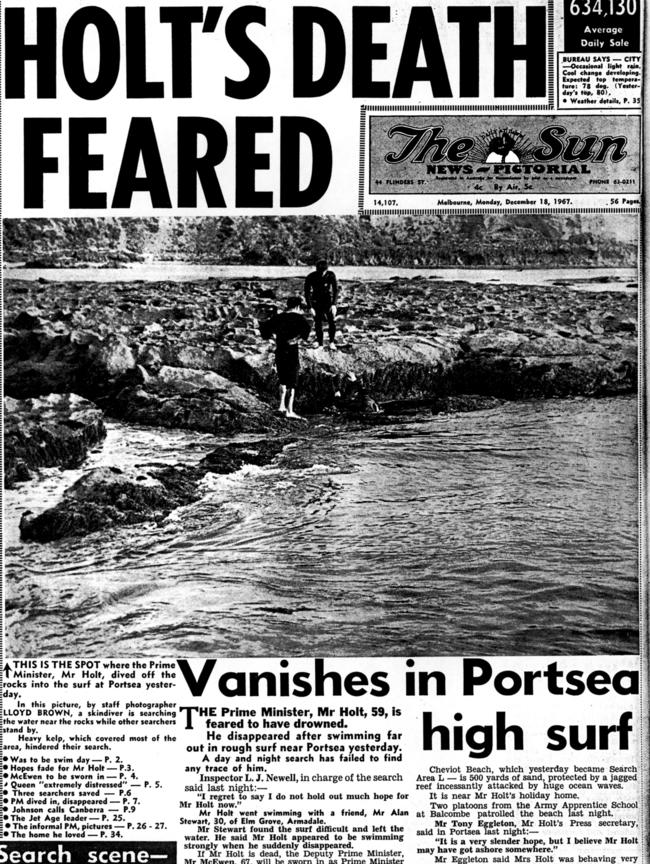

ON a Sunday morning in Portsea, Prime Minister Harold Holt was walking the gardens with his three-year-old granddaughter. A few hours later, tragedy would strike. 50 years on, those present on that fateful day reflect on where it all went wrong.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News . Followed categories will be added to My News.

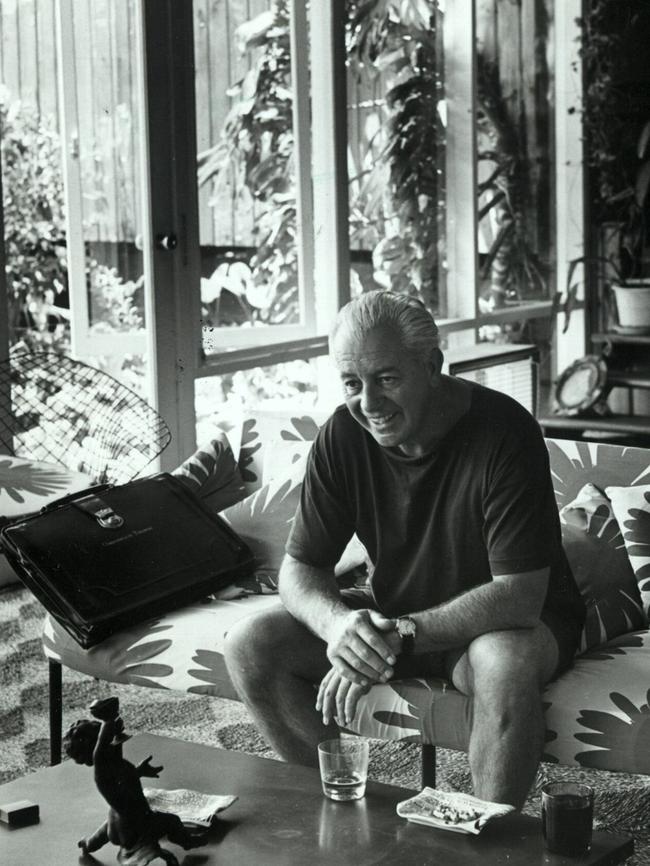

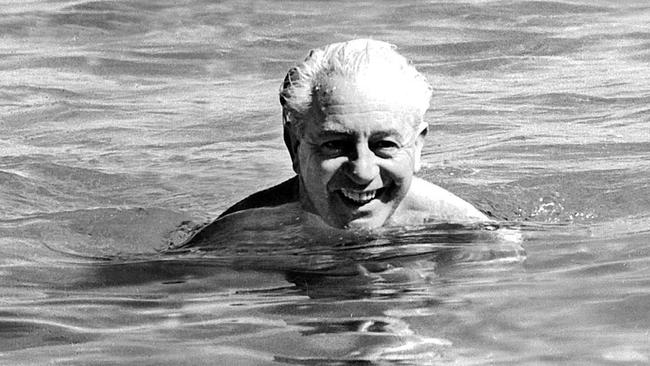

HAROLD Holt died happy, if you don’t count his last seconds as a powerful undertow dragged him under churning water and across rocks and kelp beds to oblivion.

He wasn’t ill, he wasn’t depressed — let alone suicidal — and his drowning was not caused by his bravado, despite much speculation to that effect. It certainly wasn’t sinister.

People die that way every summer — it’s just that they do not tend to be world leaders.

TRAGIC, ENIGMATIC HOLT DROWNING REMEMBERED

TRIBUTES FOR FORMER PM HOLT IN PARLIAMENT

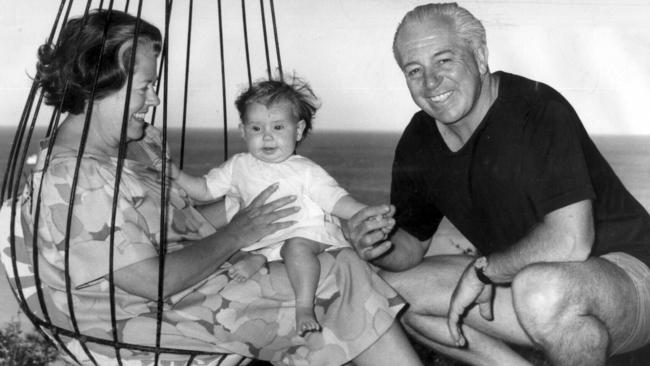

A couple of hours earlier on that December day, exactly 50 years ago this weekend, Australia’s 17th Prime Minister had just won another heart — that of his three-year-old granddaughter, Sophie.

Sophie had been shy because on previous visits her important grandfather had been surrounded by important grown-ups with no time for a little child.

But on this Sunday morning, Harold played Grandpa, walking the toddler around the garden of the family holiday house at Portsea, chatting as they looked at plants, trees and birds.

His stepson Nicky, Sophie’s father, softens as he recalls the scene: the delighted child holding the hand of the silver-haired Holt, who looked relaxed and casual in shorts, short-sleeved shirt and the old tennis shoes he habitually wore to the beach.

“The ‘old man’ came back beaming and said ‘I’ve made a new friend here!’” he recalls.

As he sifts memories of that tumultuous day, Nicky sits at the same slate dining table at which he shared the last breakfast with his father.

Nicky and his then wife Caroline and little Sophie had arrived at Portsea on Saturday, December 16. Harold was already there.

He had arrived late Friday afternoon with the family’s longtime housekeeper and cook, Mary “Tiny” Lawless, after flying to Melbourne from Canberra. His wife, Dame Zara, had stayed at The Lodge to arrange the annual Christmas party.

That Sunday morning, Nicky decided not to go to Cheviot Beach with “the old man” and the neighbours to see the round-the-world solo yachtsman Alec Rose sail his little cutter Lively Lady through the Heads.

The English sailor’s triumphant entrance was “of no interest to Sophie so we didn’t go,” recalls Nicky.

Instead, he went to the quiet bayside beach next to Portsea Pier. Which is where he was when the alarm was raised.

“A friend of mine came up and said there was drama down at the Quarantine Station and that I’d better go home. When I asked what it was he said ‘I can’t tell you’.”

But someone soon did. Bad news travels fast.

Probably the last person to see Harold Holt alive (and who is still around and willing to talk about it) is Alan Stewart, 26 at the time.

In those days, Stewart was close to the Gillespie family, whose house was next to the Holts’ on the Weeroona Estate at Portsea.

He and another young man, medical student Martin Simpson, were friends with the Gillespie girls, Sheriden and Vyner, daughters of Winton and Marjorie Gillespie.

Marjorie was one of several women linked by gossip to the debonair prime minister, whose reputation as a “ladies’ man” was an open secret in political circles, much like Bob Hawke’s would be two decades later.

Her presence at the scene has been portrayed as an embarrassment or a scandal, yet nothing that happened that day has anything to do with her presumed affair.

Whether Holt and Gillespie were ever more than friendly neighbours — as Dame Zara Holt suspected and later stated in a frank interview — has no bearing on Holt’s last frantic moments at Cheviot Beach.

About 11am that morning, Holt had telephoned the Gillespie house to ask if any of the family or their visitors wanted to come and watch Alec Rose’s entrance through the Rip. Four of them did.

Around 11.30am, two cars left the estate for the short drive to the “old fort” at the Quarantine Station, Commonwealth property closed to the general public but not to prime ministers.

Holt led the way in his maroon Pontiac Parisienne, Marjorie Gillespie in the passenger seat.

Following in a Holden was Alan Stewart, Martin Simpson and Vyner Gillespie. Army private Peter Morgan waved the two cars through the checkpoint into the Commonwealth land.

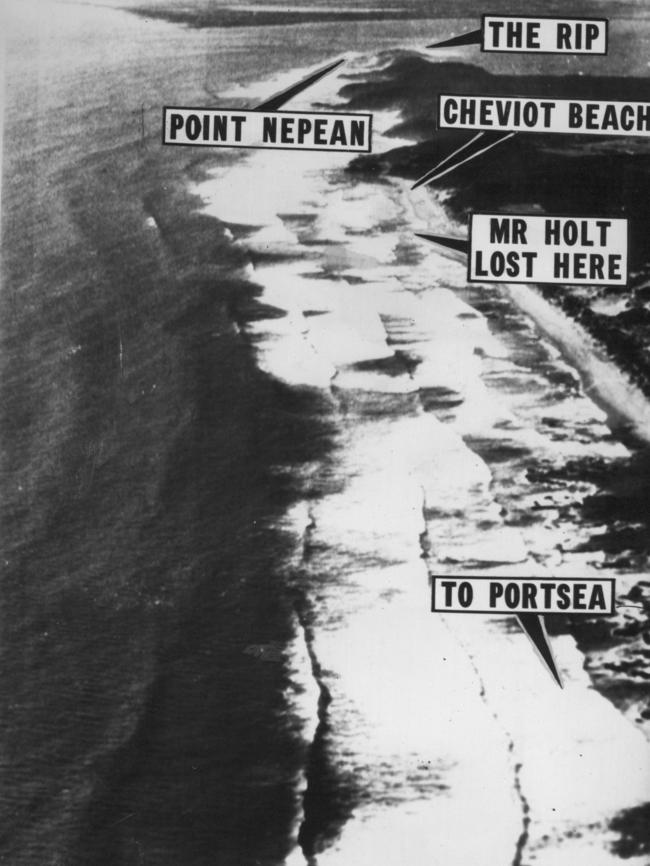

After they found a vantage point and watched Lively Lady sail into Port Phillip Bay, the Holt group drove down a dirt road towards Cheviot Beach and parked. They walked the last stretch to the water’s edge.

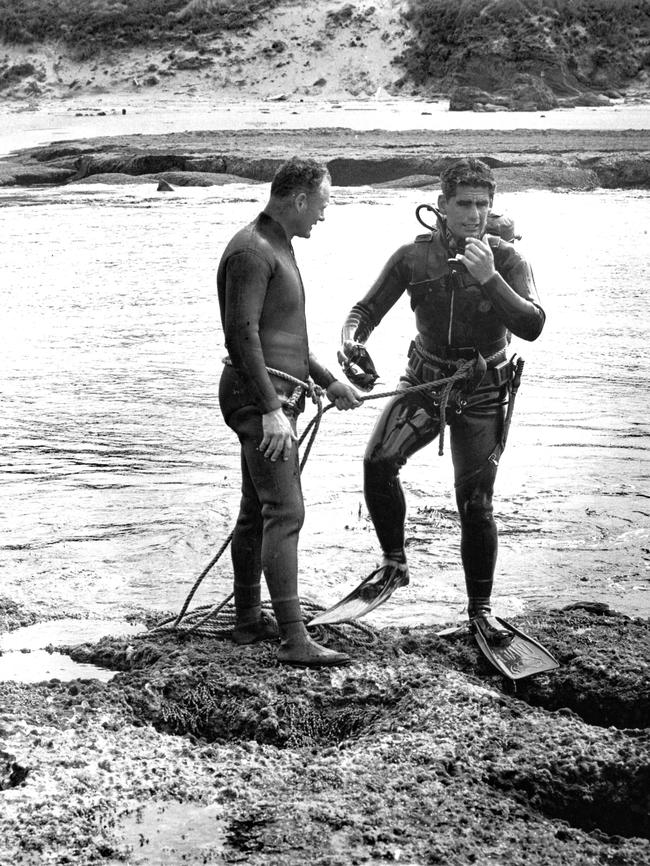

If and when the tide was out and the breeze offshore, Cheviot Beach could be a good place to explore rock pools, which were linked to deep water by channels that divers called “run outs”.

The pools were depressions in a big rock shelf jutting out into the surf, a reef that made swimming difficult, boating dangerous and surfing impossible.

At high tide, the spot could be treacherous, because big waves threw tonnes of foaming water over the rocky bottom, water that would then suck back viciously through the narrow channels, dragging drift wood, kelp — or a human body — into Bass Strait, where a swell was rolling in that day.

According to those who knew Holt — and that stretch of coast — the lull between big waves might have persuaded him to take a quick dip to cool off. He was so casual about it, says his son, he was wearing his old unlaced tennis shoes when he went into the water.

He wasn’t diving and so wasn’t wearing the flippers that made him a proficient snorkeller with his sons and another strong young swimmer in Jonathan “Jonno” Edgar, son of family friend and neighbour, Jack Edgar.

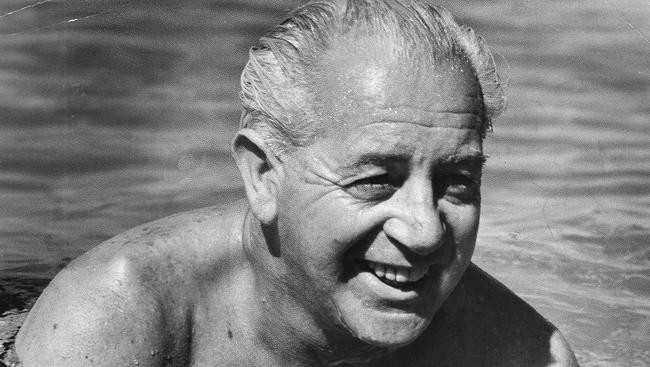

At 59, Holt was in good physical condition — despite a sore shoulder that had been nagging him — and was a fair surface swimmer, rather than a strong one. All of which adds up to Alan Stewart’s impression of a man grabbing the chance to dip himself in shallow water — and getting it wrong.

“I saw him go in. He walked into the water and was swimming around, just to cool off,” Stewart told the Herald Sun this week.

“But he had white hair and it was very difficult to see him in the foam. The surf suddenly built up and he disappeared.”

Stewart and the other young man, Martin Simpson, had waded into the water but decided against swimming, while Marjorie Gillespie and her daughter Vyner had gone walking along the beach.

Stewart puts it this way: “The undertow was very powerful. I’m only a competent swimmer and it wasn’t for me. But there was no bravado (by Holt) or anything like that. Just a tragic accident.”

The telephone was ringing when Jonno Edgar walked in the door of the family house after deciding it was too rough to surf at Portsea back beach, and too hot to lie around on the sand.

On the line was the airline pioneer Reg Ansett — “a mate of Dad’s” — who blurted “Harold’s missing” and urged Edgar to get to Cheviot Beach.

“By the time I got there, there was the army and police and God knows what,” Edgar recalls. Ansett had sent his helicopter; when the pilot asked for an observer, Nicky Holt volunteered.

The chopper swept up and down offshore but there was nothing to see in the boiling sea. It had become so rough that a police diver broke his arm. Visibility was only a few centimetres underwater because of the foam and the divers soon gave up.

Meanwhile, a cabin cruiser owned by a wealthy mining man who had rushed to join the search hit the hidden reef and capsized.

The helicopter hovered low to rescue the boat owner. All the while, the boat’s twin Mercury outboard motors were smashed off by the waves, by then up to five metres — so big that people on shore temporarily lost sight of the chopper.

Edgar says one of the motors was later sighted on the sea floor but the other was swept away and never seen again: proof of the power of the sea.

His theory is straightforward: “I think he just went in to get wet and because of the foam, the visibility was bad and he misjudged where the ‘run out’ was, stepped into it and had no way of climbing out when a wave came.”

The massive hydraulic force of the retreating water sucked out drift wood, kelp — and almost certainly a doomed swimmer — as easily as an insect caught in the plughole of an emptying bath tub. After that, says Edgar, if the body was trapped under the offshore rocks — or shredded so it didn’t float — the sea lice and other marine life would soon dispose of it.

Nicky Holt agrees with his old friend and fellow swimmer. His stepfather “was no Jon Konrads”, he explains, citing a champion swimmer of the era.

“I think it’s just a step of misfortune.”

Bill Kneebone was a young detective stationed on the peninsula for the summer. On his first day there, he got the call to search for the Prime Minister.

As soon as he reached Cheviot Beach and saw the water, Kneebone looked at his fellow detective Tony Hurley and said: “He’s dead.”

By then, he says, the sea was “like a big washing machine, full of kelp and drift wood. It would have drowned a cork.”

It was death by misadventure, he says, “like running across a railway line, falling over and being hit by a train.” In other words, the sort of fatal accident police see regularly.

David Johnston had a long career and covered some big stories in half a century in radio and television. But the newly-retired newsreader says he never broadcast anything more momentous than his opening line from the sand hills above the beach that afternoon: “The Prime Minister is missing.”

Johnston and a swelling band of reporters stayed all that week, until it was clear the huge search was going nowhere.

The contemporary media treated the story with characteristic respect but whispers about the presence of Holt’s supposed mistress added piquancy to the tragedy.

The Canberra Times headed coverage of the international memorial service held the following Friday with the headline ‘Fidelity’ theme of memorial service for Mr Holt.

Who can say if that was a barbed reference to the rumours — or just clumsy?

There are few memorials to the man who led the country for 693 days. The biggest, of course, is the Harold Holt swimming centre in Glen Iris, a tribute that has bemused generations of Australians — and astonished and delighted overseas visitors.

On Sunday, a group of Liberal Party stalwarts will gather at Cheviot Beach to commemorate the leader who went for a dip and never came back. Before they take morning tea on the sand they will recall the dashing young lawyer who entered Parliament at 30 in 1935 and would serve 32 years, the last 22 months of it as Prime Minister.

Holt’s end proves only the sea is often cruel and always treacherous, and that whenever a body is not found, mystery lingers and myths grow about the missing.

Melbourne journalist and filmmaker Iain Gillespie made a high-rating documentary in the 1980s about Holt’s disappearance.

He teased out the rumours, which ranged from the salacious to the preposterous — such as the assertion Holt was a “Chinese spy” taken away by submarine.

But, in the end, recalls Gillespie, there was no more to the story than met the eye: “The mystery surrounding his disappearance arose because he was on the beach with his mistress at the time — and so his people keep muddying the facts to try to avoid reference to that.”

Gillespie spoke to Holt’s doctor about his use of morphine for his shoulder pain, an injury that might have handicapped him a little. But people who knew Cheviot Beach best — local fishermen and keen swimmers such as Jonathan Edgar — always knew it was a perfect place to drown if you made the slightest mistake. And Holt did.

They point out that two life-size dummies were made during the days of searching and tossed in at the same spot at high tide. One was washed into the bay and surfaced somewhere near Portarlington — and the other vanished as completely as the missing outboard motor.

No wonder, then, that flesh and blood would vanish even more easily, consumed within hours by anything from sharks to crayfish and sea lice.

Gillespie’s research found that many people had drowned there over the decades. Some bodies turned up, some didn’t.

MORE ANDREW RULE:

BORCE’S ARREST, 76 WEEKS AFTER KAREN’S DISAPPEARANCE

FORMER COP ABUSED, HARASSED BUT NOT BEATEN

QUEEN ST GUNMAN NOTHING MORE THAN A DELUDED KILLER

In the 1980s, Gillespie traced a doctor who had found a human bone washed up on Cheviot Beach. Gillespie obtained the bone and kept it for years, believing it might be Holt’s.

Now the bone is gone. Gillespie suggests it was lost in a clean-up when he was moving house. But his former partner Jac Pascarl has a different version. She says their Labrador-cross dog Muckle ate it.