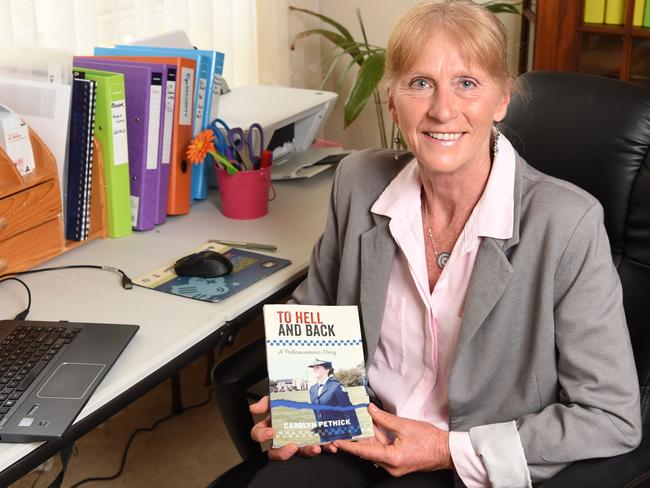

To Hell and Back: Former police officer Carolyn Pethick was abused, harassed but not beaten

SOME former and serving policemen must be very nervous about their pasts catching up with them. One woman in particular suffered all kinds of harassment at Victoria Police. First she got mad — now she’s getting even, writes Andrew Rule.

Law & Order

Don't miss out on the headlines from Law & Order. Followed categories will be added to My News.

DON Burke isn’t the only one looking over his shoulder. Some serving and former policemen must be nervous about their pasts catching up with them.

In 1981, Carolyn Pethick was fresh out of the police academy and had just started her three-month training at an eastern suburban station.

Her “boss”, a senior sergeant in his late 40s, called her into his office. Before she could sit down he snapped: “Don’t — you won’t be here long enough.” Then he snarled the sentence she can recite word for word all these years later: “I have never worked with a f … ing female and I have no intentions of working with one. So keep out of my way.”

Welcome to Victoria Police.

Crooked cops axed after assault, harassment, stalking and predatory sexual misconduct

Australian Federal Police officers complain about sexual harassment, bullying

Pethick recalls her reaction as, “Oh my God — what sort of a job have I joined?”

The naked hostility shook the former Siena College school captain but she completed her training at the station, enduring jibes from some male colleagues who objected to patrolling with a woman.

Pethick had joined the force against the advice of her family and teachers (“I didn’t want to be behind a desk the rest of my life”) and was determined to stick it out. Her next posting was with the anti-illegal bookmaking taskforce dubbed “Pittaway’s Pirates”, which raided SP bookmakers across Victoria. The team welcomed her because a female “punter” could infiltrate the scene better than most male police.

After that, she worked in “fill-in” jobs despite opposition from the men running them. She got into the Boat Squad after the boss there created a one-off “exam” he insisted she had to pass — which she did, right down to backing a boat trailer for the first time in her life. Over the following months she won the grudging respect of fellow water police.

Federal cops ‘boys’ club’ unmasked by report amid rampant sexual harassment and bullying

In the Stolen Vehicle Squad her boss tossed her a file from the bottom of the “too hard” basket and told her to get lost. The file was full of Telex messages (in German) from German police informing their Australian counterparts they believed many stolen Porsches had ended up in Australia.

After three weeks poring over records in the Road Traffic Authority in Kew, the “new girl” had found the chassis and vehicle identity plate numbers to prove the Germans were right. The cars had been imported as “spare parts”, reassembled and sold to unsuspecting buyers.

The squad busted the racket, seizing about 10 “hot” Porsches from stunned owners, most of them prominent businessmen.

Next she worked in the Vice Squad. Pethick and other policewoman went undercover — posing as prostitutes on St Kilda street corners to catch “gutter crawlers”. The crew, known as “Billy’s Angels”, arrested 100 men a month.

She was doing detective work but wasn’t yet a real detective. When she asked a senior sergeant for a reference to help her join the Criminal Investigation Branch he answered: “If you want a really good one I expect to see you naked on my desk when we get back to the office.”

CFA refers bullying, sexual harassment claims to police

Victoria Police rocked by horrific brutality claims

She was stunned to realise he wasn’t joking. When an inspector asked later why she looked upset she told him. He wasn’t surprised — just annoyed. Not that it hurt the senior sergeant in question. More the opposite.

“Nothing was said about it — but I was found ‘unsuitable’ for the CIB,” Pethick says. She thinks the fix was in. She didn’t trade sex for favours, so she was seen as a troublemaker.

She went to Mildura to fill in “for three months” and stayed three years. There she studied for her sergeant’s exam and bought a house.

“I knew I’d be walked over so I worked hard,” she says. She returned to Melbourne in 1989 to take promotion as a sergeant “who had done a hell of a lot more than some people”.

She was acting senior sergeant in charge at Balwyn when she fell pregnant in 1991. She wanted to transfer back to Mildura to be with her partner with her newborn baby but an Assistant Commissioner warned her a particular male sergeant had been earmarked for the job because he also wanted to return to Mildura.

“He’s one of the boys and they want him back there,” the senior officer explained, conceding that the rival was not as well qualified as she was. He suggested that if she appealed she would win. But when the other sergeant got the Mildura job she didn’t appeal because her baby had developed a serious illness. She had no option but to resign.

The baby recovered but Pethick’s career and relationship didn’t. She rejoined five years later, coming back as a senior constable on the understanding she would soon regain her old rank. But she struck trouble working beneath men still nursing a grudge because she had got her sergeant’s stripes ahead of them, years before.

One officer deliberately harassed her by tampering with rosters. She got proof of this when a sympathetic and childless colleague told her privately he’d been offered school holiday leave that she had been specifically denied, despite being a single mother.

Meanwhile, she was stopped from moving to other stations as an acting sergeant. She decided to file a grievance report outlining the bullying, which included having a breath-testing device thrown at her.

She filed the report at the end of a shift. When she started work next day her locker was jammed full of toilet paper. From that day her workmates shunned her, sensing she had fallen out with powerful people.

“The tension became unbearable.”

IT GOT worse. She was willing to move to a tough northern suburbs station to get away from the bullying boss but was blocked because his superiors contrived a bogus internal affairs investigation into her quite proper handling of a minor road rage incident.

She felt trapped because she could not transfer with the internal affairs file hanging over her. One night her young daughter heard her talking to a friend about how serious it could be if the fabricated internal investigation wasn’t dropped.

‘Mummy, am I going to be an orphan if they put you in jail?” the little girl asked.

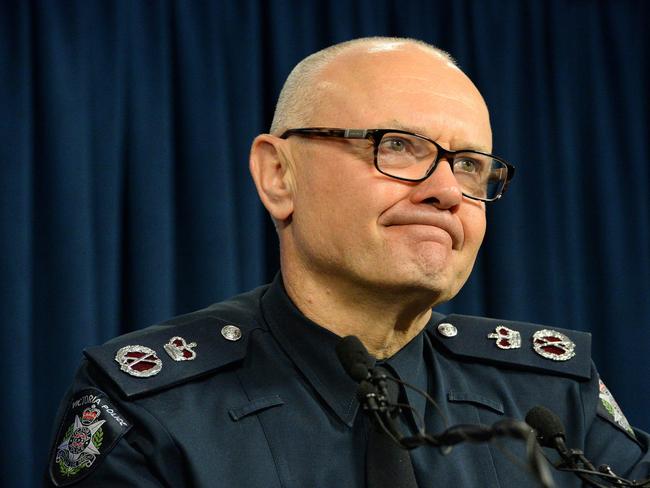

That’s when she decided to publish the book she’d written about her ordeal. She called it To Hell and Back. She gave one to Premier Daniel Andrews and one to then Chief Commissioner, Ken Lay. Then she resigned.

When Pethick read the allegations piling up against Don Burke last week, she wasn’t surprised but she was angry. Because, she says, she knew how Burke’s victims must have felt before the dam broke and they felt they could tell their stories.

“If they’d complained and reported him, it probably would have been the end of their careers,” she says vehemently, a flash of emotion from someone who long ago learned to control it.

These days she channels her feelings into the public speaking she has done since she resigned from “The Job”. She has come a long way from the idealistic 21-year-old who joined up believing she could make it in a man’s world.

First she got mad — now she’s getting even.