Gunner Colin Finkemeyer didn’t know if he would live or die when World War II ended on August 15, 1945.

The dancing in Melbourne’s streets, the confetti and stolen kisses were far, far away.

Mr Finkemeyer was holed up outside Nagasaki, a slave tending to the vegetable garden of his Japanese captors.

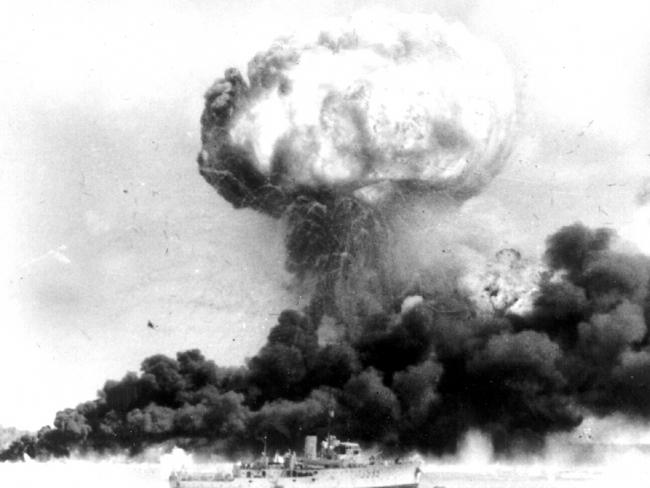

Seven nights earlier, he and mates were digging a pit when the air raid sirens went off. An orange and white cloud enveloped the city.

“Nagasaki is really copping it this time,” one of the Australians said.

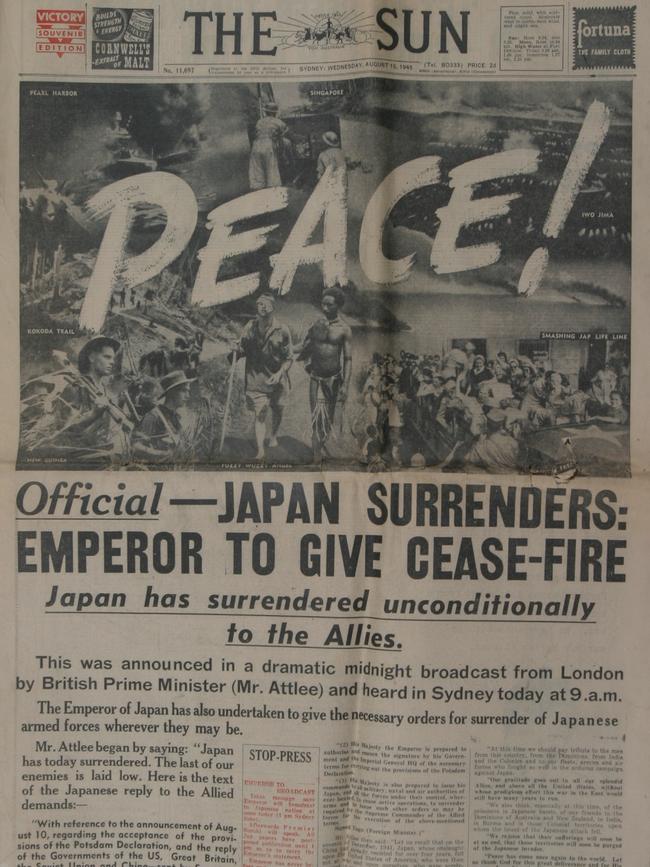

The drastic choice of atomic bombs — Hiroshima was bombed three days earlier — hastened the war’s end.

The bomb instantly killed tens of thousands of civilians in Nagasaki and probably saved Mr Finkemeyer’s life.

Australia did not know how much longer hostilities would continue after the European theatre of war ended in May.

The nation was crippled after six years of conflict. For much of the time, Australians crouched in fear of a Japanese invasion. Bombing raids of Broome and Darwin had killed hundreds.

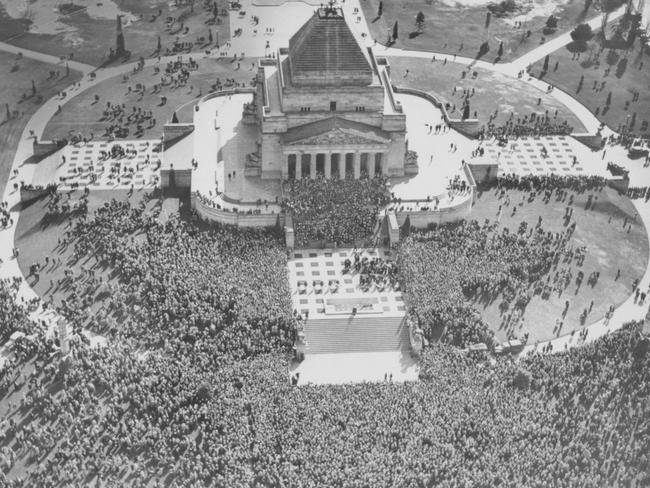

Now, on a chilly Melbourne morning, the paralysis of “pent-up emotion”, according to one newspaper, exploded into the merriment of Victory in the Pacific Day.

There was no chest-thumping; victory was received with the numbing sense of disbelief.

The so-called “dancing man” twirled and pirouetted down George St in Sydney.

In Melbourne, people thronged Swanston Street in front of Flinders Street Station to toss shredded paper and flowers in to the air.

A young chemist, Max Townsend, recalled 50 years later how he rode through the city on a horse and dray.

Peggy Warner wrote in her book, Over the Other Side: “Men, women and children danced on the roads, climbed lamp poles and monuments, rode free on the trams, ran wild in the streets. I was caught up in weaving crocodiles, kissed and twirled and tossed in the air, carried along in a merry whirl of delirious people, confetti in my hair, streamers around my neck, tears in my eyes.”

Australian troops were still fighting in Borneo at the time of Prime Minister Ben Chifley’s announcement.

Almost one million Australians had fought in Europe, Egypt, Libya, Syria, Lebanon, Greece and the Mediterranean.

Thirty-nine thousand Australians had been killed. They died for the peaceful bloom that followed the war: the migrants, the Melbourne Olympics of 1956, and the rise of an aspirational middle-class.

Japan’s plans for conquest had shifted the war focus after 1941, as the Japanese advanced through Asia, across Malaya, Singapore and Papua New Guinea.

Australian heroics in the Coral Sea, Milne Bay and the Kokoda Track would be stamped with timeless badges of courage and sacrifice.

Yet they were not fully appreciated at the time. US General Douglas MacArthur, as the Supreme Allied Commander in the Pacific from 1942, fostered a misplaced perception that the Americans were doing the fighting.

The battles on the Kokoda Track, in Papua New Guinea, brought the war close to Australia. The Japanese wanted Port Moresby, and, at the time, Australian efforts to repel them were seen to be “saving Australia”.

The skirmishes were fierce, muddy and confusing. Dysentery and malaria were rife.

Images depict bare chests and pinched faces. The photos do not express the oppressive fear of Japanese in the hills, and the surge of panic when gunfire rang out.

When the Japanese pushed on from July 1942, the Australians, new to jungle warfare, were outgunned and outnumbered.

The following month, Japanese Marines landed at Milne Bay where Australian troops, together with RAAF squadrons, defended the airfield.

It was a decisive moment, the first Japanese defeat on land in the Pacific War, and a turning point in Allied thinking: The Japanese could be beaten.

Australian military historian, soldier and diplomat Dudley McCarthy spoke of “small groups of men” who “killed one another in stealthy and isolated encounters”. Those who fell “died in the midst of a great loneliness”.

Chaplain Henry Matthews died, aged 66. Three days later, 17-year-old Acting Corporal Donald Howlett was the youngest to fall.

The Australians, boasting many soldiers aged 18 or 19, surged against the Japanese incursions in the weeks ahead.

Sergeant Jack Simms, of the 39th Battalion, later said: “Some prayed, some swore with fear, but you wouldn’t show it in front of your mates. One of the boys got shot fair between the eyes, right alongside me. It was a perfect shot. Terrible to be afraid, but it’s the brave ones afraid that still kept going, that’s what they did, you know. Scared bloody stiff and they still kept going.”

Lt-Col Ralph Honner, who commanded the 39th Battalion, later wrote that his men had “joined the immortals”.

Former Australian War Memorial director Brendan Nelson has said that 1788 was the most important year in Australian history — followed by 1942.

Of 20,000 prisoners captured by the Japanese, 7200 died. Many of the survivors returned to be burdened for life with a misplaced sense of shame about the humiliations of their captivity.

Mr Finkemeyer was luckier than thousands of his compatriots.

More than 2430 Allied prisoners were forced to march from Sandakan in Borneo. Six Australians survived — because they escaped. The rest were starved, beaten and shot.

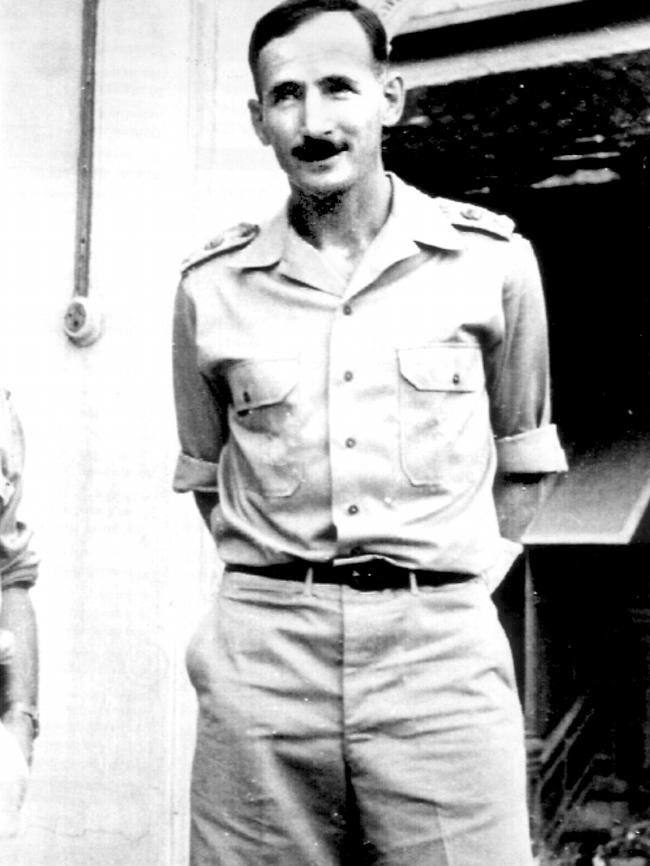

Mr Finkemeyer had not been ready for war in ’39. He was 19, at university, leading a life yet to be lived. No one was ready.

He was captured in the fall of Singapore after weeks of active service with the 4th Anti-Tank Regiment.

He was flogged on the Thai-Burma Railway and lost half his body weight.

He was jeered by locals as he straggled to work each morning. Children threw stones at the men. He was told by the ageing supervisor of his garden crew that all prisoners were to be executed in September ’45.

Then, those bombs fell. No locals lined up to insult the prisoners any more. The guards deserted the PoW camp. Mr Finkemeyer lay in his bunk. He was being attacked by fleas and lice. But he was going home.

They are nearly all gone now, the ordinary men and women who embodied a generation of dignity, resilience and valour.

Seaman Teddy Sheean, 18, defied orders to abandon ship and died defending HMAS Armidale from Japanese bombers. Whether he gets a belated Victoria Cross pales to a grander truth: His tale inspires us 75 years later.

Bill Stutt, the ace pilot who reported the advancing Japanese fleet near Bougainville, in Papua New Guinea, under heavy fire, died in 2010.

Lt-Col Vivian Bullwinkel, the nurse who was badly wounded and feigned death as 21 colleagues were machine-gunned in the shallows of Bangka Island, off Indonesia, lived to 85.

Sir Edward “Weary” Dunlop, who fashioned surgical instruments from sharpened spoons to operate on men of the Thai‑Burma Railway, is still remembered with his gentle smile.

Mr Finkemeyer, the gentlest of souls from Brighton, has gone, too. He remained close to his mates, who didn’t like talking about their experiences, except with one another.

They were cursed by the whiff of decay that took them back to hell whenever they opened an old tin or read old letters. They couldn’t let go of their pasts, and nor should we.

Mr Finkemeyer got to be a husband, father, grandfather and amateur historian.

He brought home a Japanese sword. And he wrote books about how a war ended, and why it should never be forgotten.

Learn more about the Victory in the Pacific Day 75th anniversary.

MORE VP DAY NEWS

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout