How to kick your bad habits

New year, new you. Experts say there is no habit that cannot be broken, regardless of when it took hold and how entrenched it may be. Here’s how.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

With a new year ticking over, the bad habits that seem too strong to break are due for an overhaul.

Experts say there is no habit that cannot be broken, regardless of when it took hold and how entrenched it may be.

However, professional organiser Peter Walsh, a presenter on The Living Room and author of Let It Go, says it’s better to think about replacing the habit rather than getting rid of it and to do it gradually.

“Don’t go into it cold and say, ‘Today I’ll start replacing all my bad habits’,” he says.

“You need to spend some time reflecting and thinking about the bad habits in your life, list them and try to identify howthey fit into the pattern of your life. Also look at the triggers that push you there — is looking at the fridge door enoughto get you to overeat?”

Walsh describes a habit as a pattern of behaviour that is not a one-off. It becomes deeply ingrained in daily life so thatit’s part of a routine.

While it may have begun as a pattern that brought some relief, whether emotional or physical, it can suddenly become an obviousimpediment.

“Somehow, you look around and the habit that used to be distracting or felt good becomes overwhelming because you see thatit’s just part of your life,” Walsh says.

“These habits start for a reason but get off track so you need to look at how the bad habits fit in the pattern of your life — what you wanted that habit to do for you in the first place and what is now a more positive alternative.”

Leading Melbourne clinical hypnotherapist Klaus Ruhl says every habit can be broken. The brain’s plasticity ensures that it can change, sometimes very quickly, depending on the complexity of the habit’s cause.

He likens it to a dirt road where two well-worn tracks are so ingrained it becomes difficult to not drive on the same tracks.

“A similar thing happens in the brain,” Ruhl explains.

“It’s a use-it-or-lose-it situation. You can take conscious control of anything you do

at any moment but most of the time we’re running on autopilot because it takes much less effort.

“But the neural network keeps evolving. When new connections are being made, the obsolete ones get deleted. The key is to address the cause of the habit.”

It often requires a process of observing it as a witness would to see its implications and the negative impact it could behaving on your life.

“It’s like playing a detective and asking ‘what is the purpose or drive of this habit?’” Ruhl says.

“If you see that it’s not serving you and has no possible benefit, ask what does changing this behaviour do for you? As youunderstand it more, the more simple it is to change it and it

usually falls into place, often quite quickly.”

Clinical psychologist Chris Mackey says it only takes four months for a habit to be fully broken. That is also the time frame when most relapses happen, but anyone who can get past the four-month mark should be cured of the habit.

“There are changes at a brain-connection level that are starting to gel more over a period of time, especially if you noticethe benefits of stopping the habit,” Mackey says.

“It’s about realising that it’s worth doing what’s good for you rather than what just feels good at the time.

“There will be some discomfort because our habits are programmed to some extent in our brain but we can change them.”

He advises rewards for breaking the habit such as taking a weekend away or spending the money on something else that brings pleasure.

Monitoring a habit is also a good way to diminish its power, such as calculating the amount of time spent on devices, howmany cigarettes you’re smoking or how many days a week you’re running late.

“If you see the results of your habit in black and white, it makes it real and gives you more encouragement to change.”

RUNNING LATE

Marcelle Chalita used to always be late for work. She wasn’t 15 minutes late or even five. She was only three minutes latebut every day for a year, and it was enough for her boss to comment.

“I could never get to work at 8am,” she laments. “I thought I could leave home at 7.30am and make it even though I also knewI wouldn’t make it. I used to tell myself I was just a couple of minutes late but it turned into a habit and I needed

self-discipline to get there on time.”

When she was pulled up by the human resources department at the picture frame manufacturer where she works, the 24-year-old from Craigieburn started to look at her habits.

She realised that when she first took the job she was always early but after a few months she started dragging her feet.

Her administrative job had become repetitive and there was a sense of relief in knowing that, by being just a few minuteslate, she could break the boredom.

“I was getting so used to that clock, always arriving at 8.03am,” she says.

“After I was told off twice, though, I realised it wasn’t fair on everyone else and that I’d never be taken seriously at workif I wasn’t meeting the basic requirements of my job.

“I was also getting sick of lying and I wanted to simplify my life, rise up, do well and get a pay rise and knew that wouldn’t happen if I was late every day.”

She only had to leave home 10 minutes earlier, at 7.20am, to get to work on time so she changed her routine, added a fresh dose of motivation and was gradually given more responsibility.

“My boss started to trust me more, gave me more challenging projects and he wanted to see me grow, so then I wanted to give something back and show him I was committed by getting to work early,” she says.

“Now I even work on Saturdays, because myboss wants to teach me one on one and allows me to do extra hours so I can learn and move up.”

TOO MUCH STUFF

Every time Katherine Zachest thinks about buying something new, she asks herself an important question.

“I ask ‘If I was to move house again, would I take this with me or throw it out?’” she says.

“There was a time when I was moving every two years and I became so weighed down by all our stuff that I decided I didn’tneed most of it.”

The main change in outlook came in 2012 — long before the Marie Kondo tidying craze — when Zachest, 44, of Murrumbeena, and her husband Delmar, 48, who are both teachers, decided to take a year off to travel with their children Lachie and Darcy.

It was confronting to see how little they needed to take on their travels.

Zachest had been influenced by her parents who were avid collectors of books, antiques and knick-knacks, so it seemed normal for her to also load up with possessions. But when the family went travelling, each member carried their own backpack andit was liberating to literally lighten their loads.

When they returned to Melbourne and the box of goods they had in storage, they were shocked by how much they had kept.

“I realised how little we really needed,” she says. “When we travel, we mostly go to developing countries and realise howmuch we are caught up in this consumerist society. I think experiences make up who we are and they are our most importantmemories.”

Their house is not austere and they have plenty of treasured artefacts gathered on their travels.

“It’s about eliminating the things I can do without,” Zachest says.

“I don’t look for things to buy now that are on trend and think I need to update my cushions, bedding or pots and pans. Instead,I donate a lot to Savers because I like how they’re connected to Diabetes Australia so all the money sold from my goods isgoing towards programs and services to help find a cure for diabetes.”

It is a constant process to declutter, not a massive clear-out. She works on a drawer or shelf at a time and asks herself questions during the decision process.

“I put nice music on, don’t rush and make it a nice experience as I ask, ‘Do I really need four spatulas?’”

REDUCING SCREEN TIME

A week-long holiday two years ago gave Sabijn Linssen more than a chance to relax.

When she arrived at the Koh Samui resort in Thailand, Sabijn realised there was no free Wi-Fi, limited phone reception and not even a television in the room.

She could have panicked, having been a stressed corporate professional working as a customer service manager for Webjet.

Instead, she managed to ring her husband back home in Yarraville.

“I told him I was going offline for a week and not to miss me or worry about me,” Linssen says.

“I still had my phone but consciously made a decision not to look at it. I’ve lived my life very differently ever since.”

She instantly noticed the benefits of limiting her reliance on her mobile phone and laptop. She slept soundly when she used to struggle, was less anxious and had greater mental clarity. She took another retreat in Bali last year to study yoga andit had a similar effect.

“After the first retreat I realised that I was totally fine offline and that had a big impact on me — to realise that everything still happens as it happens,” she says.

“In Bali, I was already in a more spiritual space to undertake my yoga training so I went further into that idea of switching off and to not feel guilty about not doing something. It was a way to step back.”

Now running her own events combining yoga and wine for stressed executives, the 38-year-old says the digital detox in Thailand made her question why she’d been looking at her phone at least once every hour.

Now, she looks at her phone once a day for emails and twice a day — at set hours — for social media mostly to monitor herbusiness.

OVEREATING

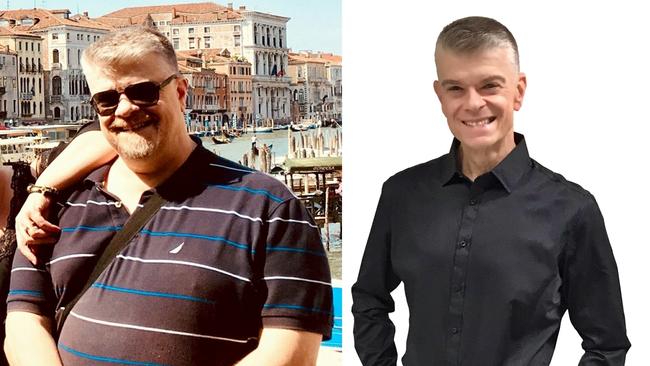

When his children asked him for a lift to the shops, Paul Averte was running out of excuses.

He really just didn’t have the energy.

He weighed 157kg and couldn’t walk 100m without feeling exhausted.

He was sitting in the family home in Bulleen one Sunday, watching his wife lead their two eldest children to the car to take them to the shopping centre.

“It suddenly hit me like a tonne of bricks that they were 16 and 17 at the time and, pretty soon, they wouldn’t need me to drive them anywhere because they’d be able to drive themselves,” Averte says.

“I was running out of time to do those simple family chores.

“Plus, we were going on a family holiday to Europe and I knew I’d need a seatbelt extension (on the plane) and I really didn’t want that.”

The 49-year-old automotive engineer says he gradually began gaining weight in year 12, using eating to relieve the stress of exams.

But the following years at university were even more stressful and resulted in him mixing the high calories of alcohol with a cocktail of takeaway food, anxiety and little exercise.

“We’d leave the pub and grab an extra-large pizza while we were waiting for the taxi, washed down with a large bottle of Coke,” he says.

“But the worst habit I accumulated was always ordering more food than I needed whether I was in a takeaway or an elegant restaurant — an extra plate of fries, an extra bowl of pasta or some more wontons.

“I’d always buy too much food, particularly bread, at the supermarket too and that habit continued through my 20s, 30 and 40s.”

READ MORE:

BEST PLACES TO EAT IN YARRAVILLE

HOW A-LISTERS LIVE LARGE AT THE TENNIS

THE STUNNING FASHION PICTURE THAT ALMOST DIDN’T HAPPEN

He had tried many diets but turned to the Cambridge Weight Plan which changed his life.

In nine months, he lost 75.2kg and is now on a maintenance program.

His meals were supplied but consisted of porridge for breakfast which he still loves, rice, curries, pasta and snacks of protein bars and shakes.

“Being a very large person when I started, food was all about volume for me,” he says. “I needed to feel full so I startedeating more slowly.

“That was the other good habit I adopted and it changed everything.

“At first, I had to force myself to eat slowly but now I go out for lunch with the guys from work and they’re wanting to get back to the office while I’m still going.”