The truth about immunity boosters and vitamin C

The immune system is incredibly complex - bafflingly so. So do things microbiome yoghurt or turmeric-infused matcha tea with jojoba really work?

Diet

Don't miss out on the headlines from Diet. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It must have seemed like the perfect collaboration. One of the parties was a yoghurt company that promised it could improve your microbiome and, in doing so, improve your immune system. The other party was Dan Davis, professor of immunology, science populariser, and a man who knows a lot about immune systems. Would he, the unnamed brand asked, consider endorsing their particular immunity-improving yoghurt?

He would, with regret, not. He turned down the offer.

Why, I ask. One problem, he says when we meet, is that while he is pretty sure that a yoghurt can change the microbiome, he isn’t sure whether that means said microbiome is “improved”. “We don’t know the definition of a healthy microbiome.”

Let’s imagine, though, that you buy the yoghurt, eat the yoghurt and, by whatever metric, your microbiome is indeed improved, whatever that means. This leads us to the next problem: just because the microbiome has improved, does that mean your immune health will too? Again, he isn’t sure.

“There is a lot of scientific evidence that your microbiome is directly interacting with your immune system. What’s less clear is how to translate that science into something medically useful.” In other words: how do you get a “good” microbiome to equal good immunity?

But the third, and probably biggest, problem with the sorts of products that he is semi-regularly asked to endorse, is that they claim to “boost” your immunity. He is not sure that “boosting” is something that you’d want to do to your immune system.

“If you boost the immune system, it will start attacking your own body’s healthy tissues.” In one sense people with auto-immune conditions actually have super-boosted immunity. “You don’t want to just boost the power of an immune system to fight things. You need it to be very precise in fighting things that are dangerous, while leaving alone healthy cells and tissues.”

If your immune-boosting turmeric-infused matcha tea with jojoba really does what it promises, it might also give you, say, rheumatoid arthritis. Which looks less good on an advert.

By this stage one can imagine the yoghurt marketing team retreating warily. Davis, however, is pretty mild about it. “I think most immunologists do get really annoyed at this stuff. Actually, most of the time, I don’t.”

So instead of putting his face on a yoghurt, Davis has written a book. Whenever he gives public talks about the immune system he finds he is asked a lot of very simple questions to which he doesn’t always have a simple answer. What is the ideal amount of sleep? Should you take vitamin C to ward off a cold? Does obesity bloat your immune system along with your belly? The answers, which he runs through in Self Defence, are rarely as simple as people would like.

The immune system is incredibly complex - bafflingly so. “It’s not true that we don’t know anything,” Davis says. “We do know quite a lot of things. But it’s also true that simple sound bites are really hard.”

So what can we do to improve our immune system?

We meet in a health food cafe in Kensington, London, near his Imperial College base. It is just the sort of place, I feel, that a professor of immunology should frequent. There are a lot of avocados. One dish boasts acai berries. There are far too many options for my liking that require liquidising kale.

I order us two juices - strawberry, ginger, apple - which are labelled in such a way to give the impression that the drink may have stress-busting properties. I consider paying extra for the collagen supplement, but decide against it on the grounds that neither of us is sure of its purpose or origin.

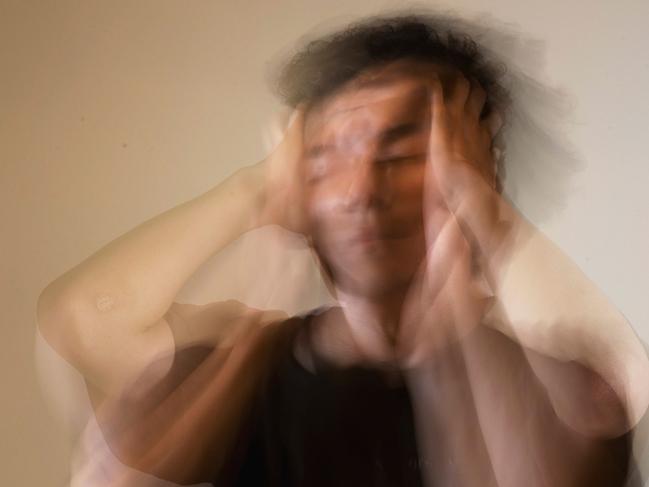

On receiving his drink Davis tells me he approves of the choice. Of all the factors that affect immune health, stress is among the best evidenced - both experimentally and in theory. “We know that when you’re stressed various hormones change their levels in your body to prepare you for a fight or flight response.” If your body thinks it faces imminent danger, then it isn’t going to worry about more long-term danger, like immune health. Laboratory work confirms this, showing that as cortisol goes up, parts of the immune system quieten down.

Now, this is fine if you do indeed need to fight or flee. But if this evolved system is activated for other reasons - if the cause of your stress is not, say, the approach of a sabre-toothed tiger, but a PowerPoint presentation - then that persistent stress, that persistent dampening of the immune system, becomes a problem.

“Long-term stress is one thing that I’d try to avoid,” he says. “Having said that, it’s not always easy to avoid it.”

Might that be where my juice comes in? He is sceptical but tries to be positive. “If it tastes delicious, maybe it will lessen your stress?” For what it’s worth, it does indeed taste delicious.

It is, actually, an unusual juice to be squeezed into this role. When it comes to the immune system, the drink of choice is orange juice. If people know anything about simple fixes for immunity, it’s that they need to take their vitamin C. Are they right? Once again, the truth is a little more complex, a little less certain.

The story of orange juice is instructive, Davis says. It helps us to understand all that has come after - with the superfoods and the acai granola and the immunologist gurus.

It begins with a man of unimpeachable authority - double Nobel prizewinner Linus Pauling. A little after receiving his second Nobel, Pauling became interested in the recently discovered vitamin C. He decided we didn’t have enough of it in our diet, so he and his wife started taking 3,000mg a day. For context, the recommended UK dose is 40mg.

He claimed, in a best-selling book, that it cured the common cold. Davis says that the fact this idea retains its hold is largely down to this, and to “one man’s evangelism”. After all, 50 years later - and after decades of supplements and countless sniffily glasses of orange juice - we have an evidence base around its efficacy.

The truth? Vitamin C doesn’t stop you getting colds. It may help you to recover - though not by much. Among people taking supplements, the best evidence is “you might get over a cold a few hours earlier”, according to Davis.

You certainly won’t - contrary to Pauling’s later claims - cure HIV or cancer, prevent heart disease or stop the negative effects of ageing.

This is why, says Davis, the saga of vitamin C is a lesson for anyone looking at the supplements market. “We have to be careful about any one person who makes claims, even if they are a two-time Nobel prizewinner.”

The irony is that two other vitamins, A and D, are known to support the immune system - although chances are, particularly with vitamin A, that you already get enough of them in your daily life.

When you realise what the immune system actually has to do, you can understand, perhaps, why a silver bullet was always unlikely.

Most of us have an idea of it as the bit of the body that attacks things that are foreign. When it spots something alien - like bacteria - it swoops in and chomps it up. If that was all it did, the immune system would be simple.

It would also be pretty bad for you. It would make the yoghurts with the good bacteria definitively useless - your body would attack them. It would, in fact, make food pretty useless; we’d be allergic to everything.

No, what makes the immune system complex is it has to be selective. It has to spot bacteria we want, bacteria we don’t, and bacteria we do want that just happen to be in a place we don’t. It also has to recognise that a sandwich isn’t a massive fearsome pathogen.

Davis’s hope, he says, is that people will come to his book hoping for answers to questions in their daily lives and come away marvelling at the intricacy and wonder of a system they have never thought of before. He does, though, hope to give them some answers for their daily lives - and unfortunately, there are no quick fixes.

Obesity, for instance, isn’t great. Ironically, this may be because being fat is, in a sense, immune-boosting. Fat contains immune cells, which means inflammation is linked to obesity. Good sleep is linked to immune health too, but what “good” means depends on the person. Moderate exercise is beneficial. Intense exercise is not beneficial in the short term. It may, though, help in the long run.

Few things, then, are simple. Except one as it turns out. Because, Davis says, there is in fact one supplement with proven and quite dramatic effects on the microbiome. This supplement works so well that for a particular deadly gut disorder, the Clostridium difficile infection, it is considered little short of a wonder cure - and is now used on the NHS.

So, what is this “supplement”? It’s a faecal transplant from someone with a healthy gut. And how do you take it?

“You ingest it.”

It’s not pleasant but it does work. And so, Davis says, there is after all a product he would endorse - if there are any purveyors of human faeces looking for some marketing assistance, he’s your man. “I could be Dan Davis: the face of shit.”