Bandido Ross Brand victim of drive-by shooting sparked by Geelong Cup bikie clash

IT was an odds-on bet that sparks would fly between rival bikie gangs at the 2008 Geelong Cup, but for feared Bandido Ross Brand it would be deadly.

Spring Racing Carnival

Don't miss out on the headlines from Spring Racing Carnival . Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT was October 22, 2008 — the day of the Geelong Cup.

The atmosphere at Geelong Racecourse was typical of Spring Carnival racing: the horses were primed and the crowd drinking in all the colour and excitement.

A group of young men, including one named Derek Bedson, was trackside that day.

That group had connections to the Death Before Dishonour (DBD) gang; a subsidiary bunch loyal to The Rebels outlaw motorcycle club.

Also at the track was a group with Bandidos outlaw bikie club connections.

The Bandidos and The Rebels had long coexisted in Geelong, sometimes with violent consequences.

It was an odds-on bet that sparks could fly between the two rival groups at the Cup that day.

Needless to say they did, and a punch on erupted.

As Crown prosecutor Chris Ryan, SC, would later say in the Supreme Court: “The fight occurred against a background of antagonism between the Rebels and the Bandidos.”

Police swooped on the hotspot and arrested one of the DBD crew.

According to Mr Ryan, the incident and the arrest angered the DBD loyalists.

“Derek Bedson in particular,” Mr Ryan would tell the jury.

DIRTY DEEDS: Our bikie special report

John Bedson, a concreter and pizza cook by trade, had spent that day at home and was driving to the Rebels’ clubhouse for a beer.

On his way he received a text to meet a couple of mates, including a Rebels member, at some shops.

Bedson parked his 4WD vehicle.

One of his mates told him about the dust up at the races.

“He just said that there’d been a fight and we had to go pick up Meat Axe,” Bedson later said in evidence in the Supreme Court.

The trio drove to the track and collected the associate colourfully known as Meat Axe.

“He was talking about how JJ had been in a fight with some ‘noms’ (nominee members) for the Bandidos, and that JJ had been arrested by the police,” Bedson told the jury.

Bedson and friends then drove from the racetrack and met up with more associates.

The six men then drove to the Bandidos’ clubhouse.

In prosecutor Ryan’s words, they headed there to “have a go”.

In other words, to fight.

According to Bedson’s version, they drove there after he received word his half-brother Derek was heading there drunk and on the warpath.

Bedson told the court he wanted to cut Derek off at the pass.

“I’d been told he was a little bit worked up about what had happened (at the races) and he was coming in to shoot the clubhouse,” Bedson told the jury.

“I wanted to go see where Derek was — make sure he hadn’t gone there yet …(and) we pulled up out the front.

“I’d jumped out — my feet had barely hit the ground when, I’m not sure. Someone yelled out ‘gun’ so I quickly turned back around, hopped back in the car and made sure everyone was in the car and then took off … It was not a very smart idea to hang around.”

DEREK Bedson was nowhere near the Bandidos clubhouse at that stage.

After the races he’d gone home.

Waiting for him was a man we shall call “Dean” due to a court suppression order.

According to Dean, Derek was angry and paced the carpet.

“He was yelling that his friend had been punched,” Dean told the Supreme Court.

Dean drove Derek towards the Geelong suburb of Whittington in Derek’s white Hilux dual cab vehicle.

On the way Derek received a phone call, and directed Dean to stop at a local pub where they met up with John Bedson.

Bedson got into the rear of the Hilux.

Conversed with his brother.

“I just told him that we’d been (at the Bandidos clubhouse) and what had happened,” Bedson told the jury.

“(Derek) said he wanted to go shoot the club.”

Bedson told the jury he saw the end of a gun — a .22 semiautomatic rifle — jutting from underneath one of his half-brother’s work vests.

“He was very, very drunk,” Bedson said of his half-brother.

“I told Derek, ‘You’re not going to do it, I’m going to do it.”

According to John Bedson’s evidence, he had no intention of killing anybody that night but wanted to send a loud message or, in his exact words, “let them (the Bandidos) know that they’d done the wrong thing”.

If that was true, his plan backfired.

Dean was told to drive to the Bandidos clubhouse, nestled in an industrial pocket in the suburb of Breakwater.

Dean told the jury he saw Bedson tie a balaclava around his face on the way.

“It was covering his nose and his mouth,” Dean said.

Dean pulled up in the darkness outside the Bandidos bunker about 6.15pm.

“I (then) heard noise coming from behind me … like some fireworks were crackling,” Dean told the jury.

“I saw John in the back holding a rifle … out the right passenger back window.”

ROSS Brand, 51, was a long-time member of the Bandidos who, the Supreme Court heard, had a reputation for often being armed with a knife or a gun.

He had prior convictions for armed robbery, assault and drug and firearm offences.

“He is no saint,” prosecutor Ryan said in court.

But there are two sides to every rough coin.

“He and his wife had been together for twenty years, married for fourteen and together they had a son who was twelve at the time,” Supreme Court judge Justice Elizabeth Curtain would say.

“Mr Brand was much loved by his family.”

Brand was at the Bandidos clubhouse drinking with a fellow gang member and two mutual friends.

One of those friends was a man named Paul.

He was not a Bandidos member.

The four men present had decided to finish up and head their separate ways, and were leaving the club when six rifle shots rang out.

One round hit Brand in the head.

Two rounds tagged Paul: one lodging in his left thigh and the other piercing his left wrist.

“We were basically ambushed and shot at,” he told Bedson’s trial.

“It looked like a car load of tradesmen finishing the day — coming back to the yard to lockup, go home … I heard the ricochets. The firing.”

The men dragged Brand back inside the clubroom as Dean drove the sniper away.

Bedson was shouting “go, go, go!”

In court, Bedson claimed he fired indiscriminately because he thought Brand was about to pull a gun.

“I thought we were going to be shot, so I just picked the gun up and started shooting,” Bedson claimed.

During the trial his barrister, Ian Hayden, asked him if he knew Brand.

Bedson: “I knew his face. I knew his reputation and that.”

Mr Hayden: “What was his reputation, as you knew it?”

Bedson: “That he’s not someone to play games with.”

Mr Hayden: “What do you mean by ‘not somebody to play games with?’”

Bedson: “He’s very quick to pull a knife or a gun.”

Prosecutor Ryan had a different take on the shooting.

He told the jury it was a deliberate attack designed to kill or seriously injure Bandidos members as a form of punishment.

Mr Ryan: “You managed to hit him (Brand) in the head, and hit (one of the other men).”

Bedson: “That’s what’s happened, yes.”

Mr Ryan: “See, what I suggest happened this particular day was this; you felt slighted because one of your friends had been hit by somebody connected with the Bandidos — that’s right, isn’t it?”

Bedson: “It’s not that big a deal really.”

Mr Ryan: “It was big enough of a deal for you to go there with a loaded firearm.”

Bedson: “It wasn’t my idea to start with.”

Mr Ryan: “It was your idea to be the shooter; you’ve told us so.”

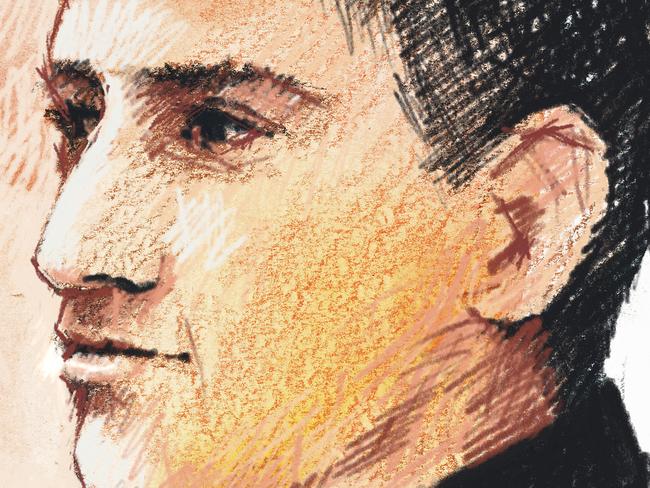

Mr Ryan suggested Bedson must have been “pretty fond” of the DBD organisation in order to pull a gun.

Bedson: “It was something I was proud of for a while, yes.”

Mr Ryan: “So proud you had the initials tattooed on your face?”

Bedson: “Yes.”

Mr Ryan: “And you were a member of the Rebels motorcycle group as well?”

Bedson: “Yes.”

Mr Ryan: “And you had your colours?”

Bedson: “Yes.”

Mr Ryan: “They just don’t get handed out, do they?”

Bedson: “You get put on a probation for 12 months.”

Mr Ryan: “You’ve got to earn them, don’t you?”

Bedson: “You’ve got to do as you’re asked; serve drinks, clean the club house, look after the

bikes on runs, yes.”

Mr Ryan: “They don’t just give those colours out to anybody, do they Mr Bedson?”

Bedson: “You’ve got to have 12 months to show that you’re dedicated, that you’re going to stay, you’re not going to just leave.”

Mr Ryan: “And you were dedicated to the Rebels?”

Bedson: “Well yes I was.”

According to driver Dean, Bedson said “I think I got one” as they drove away after the gunfire.

Brand and his injured mate were rushed to the Geelong Base Hospital.

Brand was transferred by helicopter to The Alfred Hospital and died hours later.

John Bedson pleaded not guilty to murder and attempted murder.

In his closing address, Mr Ryan told the jury Bedson had strong motive to take revenge on the Bandidos.

“At the moment John Bedson fired that rifle he was a DBD. He was a Rebel,” Mr Ryan said.

“And so far as he was concerned, one of his associates had been hit by a Bandido at the racetrack. He was slighted.

“My submission to you is John Bedson went back to the Bandidos to punish them.

“In my respectful submission it’s as plain as punch that (Brand and the others) were silhouetted against the open doorway of the Bandidos clubhouse. Those shots were directed towards these men.

“In fact, if it wasn’t so serious, you’d say of Mr Bedson it was damn fine shooting.”

In September 2010, the jury found Bedson, 27, guilty of murder and intentionally causing serious injury.

Justice Curtain sentenced him to 23 years’ jail with an 18-year minimum.

“It appears that your conduct was motivated by misguided loyalty to the honour of The Rebels or Death Before Dishonour and, in that distorted perception, you came to the view that you were justified in taking retaliatory action,” Justice Curtain said.

Bedson unsuccessfully appealed against his conviction and sentence.

Derek Bedson, a 23-year-old apprentice carpenter, pleaded guilty to manslaughter and reckless conduct endangering life.

In March 2011, Justice Curtain sentenced Derek Bedson to 12 years’ jail with an eight-year minimum.

“It was your decision to shoot up the clubhouse, apparently as a retaliatory act,” she told him.

“You were not a member of the Rebels motorcycle club, nor were you a member of Death Before Dishonour, but nonetheless you must have acted out of some sense of allegiance — if only by reason of your brother’s connection to those groups.

“It is fair to say that, had it not been for your response to what occurred at the Geelong Races, these events would never have occurred.”

Derek appealed the length of his sentence, and had it reduced to eight years with a five-year minimum.