How undercover NSW police officer busted three crime gangs at the same time

One cop juggled multiple fake identities to simultaneously infiltrate and take down three separate crime syndicates, including one headed by Michael Ibrahim. Here’s how he did it.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Bikie associate Bredan Paul Dries was so happy when he sealed a deal to smuggle $80 million worth of ice into Australia that he made a bold request to his partner in the operation.

“Would you sell me your share?” Dries asked, according to documents tendered in Penrith District Court.

As they stood outside the Ettamogah Hotel in Kellyville Ridge at 5.36pm on November 18, 2016, Dries didn’t know it, but his partner was harbouring several secrets.

The man who paved the way for the Dries’ syndicate to import the drugs was an undercover cop operating under an assumed identity.

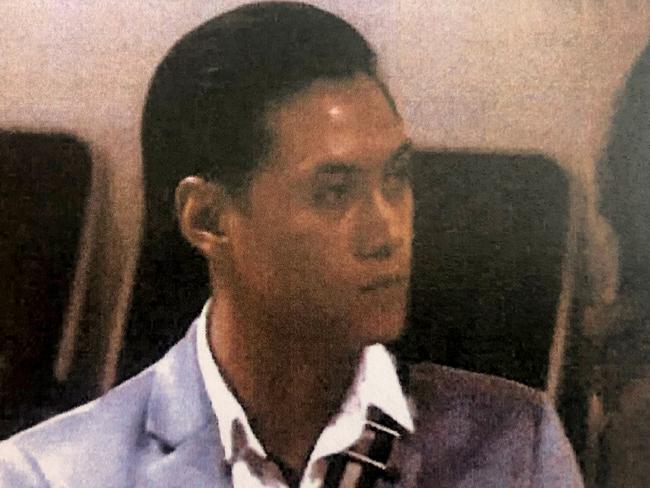

Dries, 37, had not only doomed himself, but also the Sydney-based Asian drug lords who smuggled the 1.3 tonnes of ephedrine — a precursor for ice — from China.

There were several other things Dries didn’t know.

In addition to the name Dries knew him by, the undercover had at least one other assumed identity.

When he wasn’t meeting with Dries and his crew, the undercover had been using another alias to simultaneously infiltrate and take down another crime syndicate on the other side of Sydney.

At 10.30am that morning, the undercover had used his alternative identity to meet one of his other targets, Michael Ibrahim — the younger brother of Kings Cross identity John Ibrahim — at Double Bay cafe Twenty-One Espresso, court documents said.

At the meeting, Michael’s underling gave the undercover an encrypted BlackBerry phone to communicate about drug and cigarette smuggling, the documents said.

The undercover would use the second alias again three days later when he met Michael and Sydney drug lord Mostafa Dib in Rose Bay to arrange an 800kg MDMA shipment to be smuggled into Australia.

But there was still more.

Sources said he did undercover work on a third case at the same time.

It was known as Operation Astatine, which exposed crime figures smuggling MDMA from the Netherlands and a corrupt Australian Border Force official, Craig Eakin.

By the time he completed his work on the three cases in August 2017, the undercover had Michael’s syndicate on the hook for almost two tonnes of MDMA, cocaine and ice, plus millions of illegal bootleg cigarettes.

One month earlier, the undercover had finished with Dries and the Asian syndicate. He had them pinched for smuggling 1.3 tonnes of ephedrine and almost three million illegal cigarettes.

The Astatine investigation also finished in August 2017. Eakin was later jailed alongside the crime figures he assisted.

The three investigations began in 2016 and the undercover’s work in all of them overlapped.

His stint infiltrating the Ibrahim clan stretched from June 2016 to August 2017. From September 2016 to June 2017, he was jumping in between Michael Ibrahim’s crew and Dries’ syndicate.

It is understood his work for Astatine began around early 2016.

The other remarkable aspect was how the undercover managed his simultaneous infiltration of the syndicates.

He juggled at least two fake identities and their backstories. He kept track of text conversations he had with an expanding number of criminals about drug imports using at least seven encrypted BlackBerry phones — taking photos of the exchanges for evidence.

He risked his life when two of the syndicates became suspicious he was a cop.

It was either luck or the watchful eye of police surveillance teams that prevented the syndicates from bumping into each other.

The evidence collected using the undercover’s hidden recording devices and text exchanges, helped form watertight cases against the syndicate’s kingpins.

Most of them pleaded guilty and are now in jail.

The undercover’s fearless pursuit took him international, and he maintained communications with multiple syndicate members across different time zones.

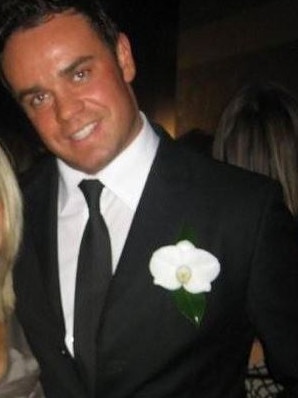

In November 2016, he attended a Thailand holiday with Michael Ibrahim where they discussed smuggling plans.

Around the same time, he was receiving BlackBerry messages from Dries asking about the ephedrine: “Hey u 100percent this is going to work hey with no headaches or jail?”

By June 25, 2017, the undercover had infiltrated the Asian syndicate to a level where he sent its mystery members a BlackBerry message to let them know their 1.3 tonne drug shipment would soon land in Sydney.

Their identities were exposed when surveillance police watched the syndicate members read the messages sent by the undercover and then celebrate with “high fives”.

One of them declared: “F. k, I’m going to be rich, man”. They were soon arrested.

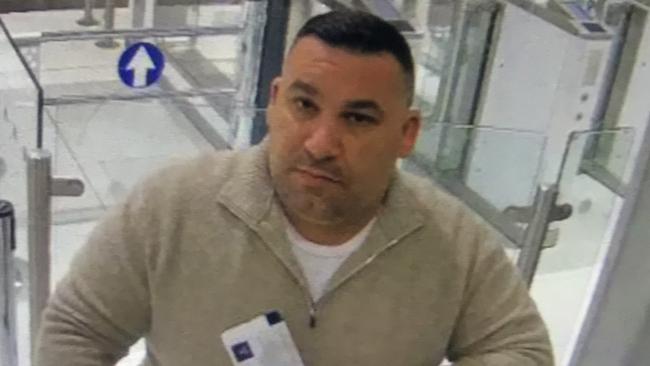

Four days earlier, the undercover had been in Dubai for the Michael Ibrahim investigation where he had sat for dinner with exiled Sydney drug boss Hakan Arif at the up-market Zuma restaurant.

Arif, also known as “Mr Billionaire”, discussed plans to smuggle huge drug shipments to Australia and boasted about having “people on the inside” — blissfully unaware there was one sitting opposite him.

WHO IS SUPER COP?

Very little is known about the actual identity of the undercover — even less can be published.

The NSW court system has suppressed his identity to the level where it is illegal to reveal almost every detail about him.

His real name is a deeply buried secret of his employer, the NSW Police Force.

On official police documents, he is only identified by a code name that is an acronym followed by three numbers.

His aliases are suppressed. So is anything that reveals his physical appearance or the sound of his voice.

One of the few things that can be said is that he was under the age of 30 when he took down the syndicates.

Some of the few people who know what he looks like are the ones he put in jail.

THE HIT LIST

The list of criminals the undercover has sent to jail features an all star cast of Sydney underworld figures.

His methods have attracted criticism from defence lawyers who claim it is entrapment.

But his CV features more hits than misses.

Michael Ibrahim was sentenced to a maximum 30 years jail for drug and tobacco importation.

Ibrahim’s barrister, Bret Walker SC, told the court that the undercover entrapped his client. Sentencing judge Dina Yehia retorted: “However, once the opportunity was presented, the offender embraced it.”

Ibrahim’s offsider, Ryan Watsford, was sentenced to up to eight years in jail for drug importation.

Western Sydney heavyweights Ahmad “Rock” Ahmad, Mostafa Dib and Hassan Fakhreddine were sentenced to more than ten years for drug smuggling.

From the ephedrine syndicate, Quoc Kiem Tran and associate Jeffrey Acosta were sentenced to between six and ten years jail.

Dries was a rare miss and was sentenced to between five and nine years jail despite being the chief facilitator of the plot.

His lawyer Leo Premutico said negotiations with the DPP resulted in an offer being accepted for Dries to plead guilty to aiding and abetting the syndicate, rather than importing a commercial quantity of illegal drugs.

“Mr Dries did not have access to large amounts of drugs — he introduced the (undercover) to people who did, ultimately he was caught in the middle,” Mr Premutico said. “He aided the communication between the (undercover) and others, and nothing else.”

Eakin was jailed for a maximum of four years after pleading guilty to using his ABF position to help smugglers.

HOW HE DID IT

The police play to inject the undercover with each of the syndicates was well planned and meticulously executed.

The move to get him in with Dries’ crew took shape on August 27, 2016, and involved another undercover officer.

The other officer infiltrated an out of town drug network and told one of his targets he had a friend who specialised in smuggling illegal goods over the Australian borders. The friend was the undercover.

The target sold the officer an encrypted BlackBerry phone for $2400, which he said could be used to connect Dries.

The target added that Dries was interested in importing drugs.

Dries agreed to meet the officer at Nepean Village Shopping Centre in Penrith just before 11.30am on September 9.

This was the opportunity for the officer to introduce the undercover to Dries.

From there, the fast talking undercover worked his magic, and captured every word on a hidden recording device.

He expertly mimicked the behaviour of a seasoned organised crime figure.

Court documents explained how he disarmed and dazzled Dries with his personable style and expert knowledge.

But they also showed how he balanced his delivery with a firm degree of paranoia.

The undercover explained his “capacity” and the “prices” he charged to smuggle drugs.

He told Dries he could facilitate the imports by “organising the clearance of air freight and sea freight cargo through the Australian Border Force security monitoring system”.

Dries asked: “Is it 100 per cent guaranteed?”

The undercover replied that it depended on how careful Dries was prepared to be.

He then instructed Dries to follow the rules: Never provide your BlackBerry code name to anyone.

If Dries had any questions, he was to ask the undercover. No exceptions.

The undercover’s subtext was clear: You need me, I don’t need you.

Dries was in.

Soon after, the undercover was provided with a BlackBerry to communicate directly with Dries about future drug importations.

The undercover’s BlackBerry username was “Robotwolf”.

Dries’ was “Shazza”.

****

The undercover infiltrated the Ibrahim clan via their minion Ryan Watsford. By August 2016, he was running a similar play: authoritative and very cautious.

At one point, he told Michael Ibrahim: “I don’t like drama, I walk away.”

In November 2016 when the bumbling of Ibrahim’s syndicate threatened a six-figure cash exchange for millions of illegal cigarettes, the undercover blew up and refused to deal with them.

In September 2016, the undercover tore strips off Dries when he short changed him by $650 on a $25,000 cigarette deal.

****

Once the undercover had asserted his authority, he drew his targets in further with the second tactic in his playbook.

He is naturally charismatic, appears to have a very high IQ, and is a brilliant conversationalist.

It started the second he made contact with a target.

He hit them with a warm “hello mate”, which was often blended with a laugh.

The effect of the delivery was deliberately disarming and made the crooks feel like they were on the undercover’s inner circle.

They didn’t know it, but it was the other way around.

****

The undercover’s final play was the delivery of his services.

It was a slow burn move.

They didn’t import drugs straight away. The undercover eased his targets in by delivering millions of illegal cigarettes, which can be sold on the black market for a lucrative return.

The syndicates believed cigarette smuggling was a low consequence way to test the undercover’s smuggling abilities.

On September 21, 2016, Dries wrote to the undercover: “(Asian) side we sat down yesterday we thinking of bringing a container of smokes to trial before bring the good shit in to minimise the risk and build trust.”

At a meeting on November 10, 2016, Michael Ibrahim fell into the same trap with the cigarettes when he told the undercover: “Trust me you’re helping us all out. That’s why we don’t want to upset you. We want to do some business. We want to show you that we can do it.”

After a number of successful shipments of millions of cigarettes, his targets were comfortable.

The undercover then opened the door for them to smuggle huge quantities of drugs into Australia. They all took the opportunity.

BlackBerry JUGGLING ACT

Almost all serious organised crime is co-ordinated on encrypted phones these days.

It causes a headache for the police, because it keeps them out of the conversation.

The military grade encryption means that, for the most part, police can’t listen in on the calls or monitor the text messages.

In these cases, it required the undercover to infiltrate both syndicates’ communication circle.

Once he was on the inside, it was revealed to him how many other people were involved in the drug syndicates.

This was because the kingpins at the top of the drug hierarchy were using the same encrypted networks to send instructions to those further down the chain.

Eventually, all of the messages were forwarded to the undercover and he started collecting BlackBerry usernames.

His next challenge was to match the usernames and aliases with the identities of the drug smugglers.

And that is exactly what he did.

The undercover won the trust of his targets to the point where they gave him encrypted BlackBerry phones to communicate with him about drug and cigarette importations.

But it wasn’t just one phone.

The undercover had to keep across communications with different criminals on seven encrypted BlackBerry phones for the two investigations.

Six were given to him during investigation into Michael Ibrahim’s syndicate. Only one was given to him by Dries’ syndicate.

This meant he had to remember which phone was which, who he was talking to on each phone, and what he had said to them previously.

All while juggling multiple false identities and convincing his targets to reveal more about their operations.

He made it look easy.

Each time he sent or received a message with one of the syndicate members, he took a photo of the screen and stored the exchange as evidence.

By mid September, court documents showed the undercover had Dries confirming via a BlackBerry that he wanted to import drugs into Australia.

At this stage, the undercover did not know the identities of the Asian syndicate members connected to Dries.

On September 9, 2016, Dries sent the undercover a BlackBerry message explaining early plans to smuggle drugs, including weights of 40kg to 50kg by sea and air freight.

He also alluded to how their partnership would make them both rich.

“Sweet we stick to sea an big lots this will be a good thing bra as u clear it we laughing,” Dries’ text said.

The same day, Dries sent another message revealing he had access to ice and pseudoephedrine.

“Fryed (ice) 100percent and sued (pseudoephedrine). In the 3monts window can we do 1 or 2 shipments if its in different containers,” Dries wrote.

A further message that day showed Dries was keen to get started.

“Yer mad done,” Dries wrote. “I will send details tomorra onces I sit down an work it out on numbers an places but it will be fryd (ice) the first run bra.”

On September 12, Dries revealed the source country for the drugs, the plans for a trial run, and that his other syndicate members were very cautious.

“Hey bra it will cum from China,” Dries wrote. “How much notice do you need before its arriving. Wats last date it can get here before the door close for this run.

“It will be 1 shipment the first time and (trial) to make sure,” Dries wrote. “Then we will do multiple big ones. They don’t want heaps of people knowing bra.”

Over the following days, the undercover told Dries via message that his fees were either $100,000 cash and 15 per cent of the imported drugs or no upfront cash and 20 per cent of the drugs, according to court documents.

He added that he could provide the name of an importation company with a clean history to facilitate the clearance of the drugs for a $30,000 fee, the documents said.

*****

Two months earlier, the undercover was using his other alias to infiltrate Michael Ibrahim’s syndicate when he had a breakthrough moment thanks to some quick thinking.

On July 21, 2016, the undercover brought his own BlackBerry to a meeting with Watsford at the Sheraton on the Park.

After convincing Watsford he was a professional money launderer, the pair resolved to exchange contact details.

Watsford handed the undercover his BlackBerry and told him to send a message to his own phone.

The undercover, whose username was “urfavdelimeat”, sent the message revealing that Watsford’s username was “city2”.

It was the first step on his climb up the criminal ladder

*****

USING BlackBerry PHONES TO CLIMB THE CRIMINAL LADDER

Once he was inside the BlackBerry communication circles, the undercover used his skills to discover who was at the top of both syndicates.

At a meeting in the Penrith Panthers Club car park on September 15, 2016, Dries revealed to the undercover that “the Asians” were at the top of his crew.

It was good information, but the undercover didn’t know the Asians’ identities.

Over the next 12 days, the undercover sent messages about his services and prices to Dries who forwarded them up the line.

A breakthrough came on September 24 when Dries forwarded one of the replies from the Asian syndicate to the undercover.

It came from “Mr Empire”.

Two days later Mr Empire sent another message to Dries that said: “Tell the customs guy we will do (pseudoephedrine) project with him when we get back from China.”

As more messages were sent, more codenames emerged. “Big A” and “9 Dragons” were interested in illegal cigarettes.

On October 10, 2016, Dries forwarded the undercover a message from Mr Empire requesting delivery of 1.5 million cigarettes to an address in Lansvale.

Quoc Kiem Tran, Jerrery Acosta and others arrived at the scene, court documents said. Tran handed the undercover $375,000 for the cigarettes.

In October and November, police monitored Dries, Tran, Acosta and others as they flew to China to approve the 1.3 tonnes of pseudoephedrine to be shipped to Australia.

On November 2, Dries confirmed the drug smuggling plot by sending the undercover two messages, including one that said “Hey u 100percent this is going to work hey with no headaches or jail.”

By December, Dries had forwarded the undercover more usernames, including “Uncle.eight” and “Bromate333”.

Dries also messaged the undercover to ask if he wanted his share of ephedrine “done up” into ice.

But in January, he also warned the undercover not to sell his share of the drugs too cheaply.

“ … If you do decide to sell sum make sure it's a price we give u bra so it doesn’t drop the market,” Dries wrote.

The drug shipment arrived in Sydney on June 24, 2017, and was seized by authorities.

The pseudoephedrine was hidden inside 120 buckets of “sea salt”.

Police converged on the syndicate’s Seven Hills office the next day.

The undercover sent messages to the BlackBerry usernames attached to the Asian syndicate telling them the drug shipment arrived.

The police monitoring the Seven Hills office watched as the men received the undercover’s message and celebrated before arresting them.

****

The undercover had been working hard at that stage of the investigation.

Two days before, he sent the message to Seven Hills crew, he had been in Dubai having lunch with Hakan Arif, the Dubai based drug boss, for the Ibrahim investigation.

He also had a lunch with 45-year-old European MDMA manufacturer Nejmi Saki at another restaurant, Torro- Torro, on the same day.

“I have a large stockpile of drugs in Turkey,” Saki told the undercover. “I have 7600kg of liquid to produce MDMA and can produce 300kg a week through three factories in the Netherlands.”

Saki, who escaped arrest in August 2017, gave the undercover a BlackBerry so they could have direct contact and explained he was flying to Germany to meet “other partners”.

The undercover had found his way to Arif and Saki using a similar method to what he used with Dries.

He communicated about the drug importations via BlackBerry with Michael Ibrahim.

He soon discovered there was a chain of communication where Arif, Fakhreddine and Ahmad sent messages to Dib and Ibrahim.

The latter two then forwarded them to the undercover who set about infiltrating the structure.

****

NOT GETTING CAUGHT

With a maximum penalty of life sentence in jail, the stakes are as high as they come for criminals smuggling commercial amounts of illegal drugs into Australia.

So when a shipment is in transit, or close to it, paranoia levels skyrocket. And so too do the danger levels for the undercover cops setting the traps for their targets.

It was at this point that both syndicates began asking questions about the undercover’s authenticity.

On January 30, 2017, Dries met with one of his underlings and demanded he “source further details regarding the background” of the undercover, court documents said.

Dries explained this was to “ensure he was not an undercover police officer” and he “threatened to abandon the pseudoephedrine importation operation”, the documents said.

The underling found nothing and the operation continued.

The undercover had a similar occurrence on May 5, 2017, while investigating Michael Ibrahim’s syndicate.

Ibrahim got suspicious. So he and Watsford paid a private investigator to follow the undercover after he drove away from their lunch at Point Piper’s Royal Motor Yacht Club.

The quick thinking undercover spotted the PI and wrote a message to Ibrahim warning him that he suspected he was being followed by the police.

Michael blamed his underlings.

WHERE TO NOW FOR THE UNDERCOVER?

The short answer is we will never know.

The status of undercover police is a tightly guarded secret and police refuse to comment.

One safe conclusion is that members of the Sydney underworld know what he looks like.

So if he is to work undercover again, it might be in an area completely separated from the Sydney underworld.