Northern beaches facing rise in homeless teens, and hidden problem predicted to worsen

DESPITE its perceived affluence, youth homelessness is growing so rapidly on the northern beaches that intervention agencies are moving in.

Nth Beaches

Don't miss out on the headlines from Nth Beaches. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE northern beaches is depicted as a paradise on the thousands of postcards tourists send back home every year. But behind some closed doors the situation is very different.

A rising number of parents and children are in conflict and the result is a shocking increase in homeless teenagers.

Today there are calls for the community to face up to the problems on its doorstep and for parents, who may be embarrassed about the situation to seek help sooner.

Lisa Graham, chief executive of Taldumande Youth Services, says most of their homeless youths — the term “youth” refers to young people aged 12 to 24 — are generally not sleeping rough on the streets but “couch surfing” at friends’ homes.

Ms Graham says that while most times youths have found themselves homeless due to a total breakdown in relations between them and their parents, some are escaping domestic violence, or are the perpetrators, have parents with mental health issues, or are suffering themselves.

Excessive use of alcohol or drugs — ice in particular is an emerging problem on the beaches — can also lead to family conflict.

Single parent and blended family situations are most at risk of a breakdown in family relations, which can lead to homelessness, she says.

Another factor is the very high cost of housing on the peninsula, where even if both parents are working, it can still mean finances are a struggle.

But it is not just those “stereotypical” families that find themselves in difficulty, but wealthy families too.

Well-to-do parents tend to bury their heads in the sand when problems arise in the family, Ms Graham says.

“They don’t think this situation can happen to their family and therefore they don’t reach out for help until the family is at crisis point, because they are too embarrassed.”

Ms Graham says that another cause of homelessness can be neglect — not in the traditional sense, but if both parents are working they are time-poor and not always as connected to their children’s lives as they should be.

StreetWork, is one of several agencies helping homeless and troubled youth on the northern beaches.

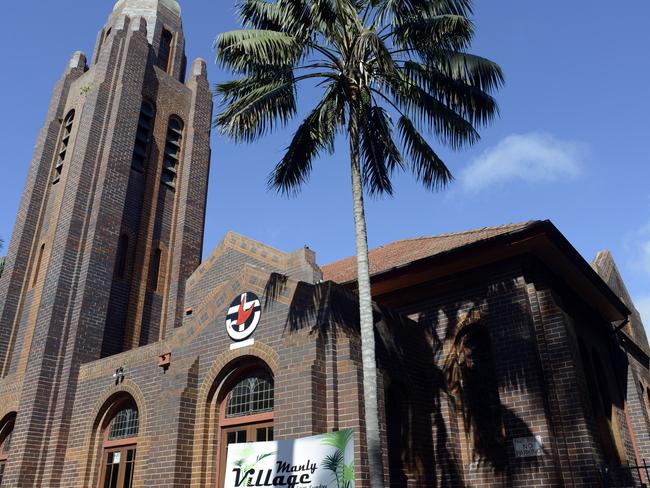

This week it has set up a permanent base in Manly because of rising demand.

Tim Sheerman, one of the youth workers, says the large teen population of around 30,000 is just as “at risk” as any other part of Sydney, despite this being an affluent area.

Along with his colleague Thomas Dent, who will be permanently working out of Manly Village Uniting Church, they aim to engage with troubled youths where they tend to hang out.

They have chosen a base near The Corso, one of Sydney’s biggest tourist attractions, but also one of the many places vulnerable teens can be found; along with Warringah and Warriewood malls, skate parks and graffiti walls.

Mr Dent says modern-day parenting is a contributing factor in some cases.

One example is “helicopter parenting”, where parents monitor every aspect of their child’s life and have incredibly high expectations.

“When you have high-achieving, high-performing families, there is often a pressure to perform,” he says.

“It can lead to children self-harming or participating in risky behaviour.”

Neil Davies, from Burdekin, another homeless provider on the northern beaches, agrees with this sentiment.

“There are those who impose unrealistic boundaries and consequences,” Mr Davies says.

“Other parents would rather be mates or be considered “cool” rather than be a parent and impose appropriate boundaries.

“An example of this is the culture and normalisation of drug and alcohol misuse.”

Phil Nunn, a psychologist from Seaforth with 20 years’ experience, who runs a help website workingwithyouth.com.au, says parents struggling with young children, aged five or six, need to seek help early, in order to prevent problems which may arise in their children’s teen years.

He says that communication problems between parents and kids can occur in all types of families, even children from very wealthy and educated families. He has found gay youth are particularly at risk of becoming homeless, because some parents find it difficult to come to terms with their child’s sexuality.

“One in ten people are gay, while three out of ten homeless youths are gay,” he says. “The statistics speak for themselves.”

He says other children fall out with their parents over trivial matters.

“I had one kid who moved out because parents wouldn’t buy them a car for their 18th,” he says.

“I often have to explain to children that living in a hostel is not a better option and that they will often have to do more chores there and abide by stricter rules.”

He says he encourages both the adults and the children to come up with a set of rules that they can all live by and they can both agree on.

“Being homeless is very unsettling,” he says.

And it takes around 2 ½ years for a young homeless person to get out of the homelessness cycle and have some kind of independent stability, says Mr Nunn.

Ms Graham says today’s youths are different from previous generations.

“They are concerned about the world, have a high sense of their rights, but a low sense of responsibility,” she says.

”It’s a difficult combination to manage.”

For more details or information about youth homelessness visit:

streetwork.org.au; taldumande.org.au and burdekin.org.au.

Follow Julie Cross on Twitter @juliejourno