‘I shouldn’t be here’: What it’s really like in a mass shooting

Survivors of one of the world’s worst mass shootings have spoken about the killer, including his “polite” request as he killed 49 people.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WARNING: Confronting content

As bullets fired from an assault rifle flew over the bar in rapid succession shattering glasses and spirit bottles, Kate Maini, crouching terrified beneath the counter, clutched onto her co-worker Juan.

Coloured lights still danced around the nightclub but the Latin music had been replaced by screams.

At least, mum-of-one Ms Maini thought, she was silent so the gunman wouldn’t make her his next target.

Except she wasn’t silent. She wasn’t silent at all. She too was screaming; shouting her son’s name over and over.

“I didn’t even realise I was making a noise or saying anything out loud,” Ms Maini tells news.com.au.

“Thank God that kid was there to shut me up. He’s like, ‘you’re gonna get us killed’.”

In a nearby toilet, Orlando Torres was hiding in a cubicle, listening as people were shot around him.

At one point, he felt the killer’s hand caress his back, apparently to check if he too was dead.

“I shouldn’t be here,” Mr Torres says. “Something protected me.”

Stream more US news live & on demand with Flash. 25+ news channels in 1 place. New to Flash? Try 1 month free. Offer available for a limited time only >

Ms Maini and Mr Torres were both at Pulse, an LGBTI nightclub in Orlando, Florida, on June 12, 2016.

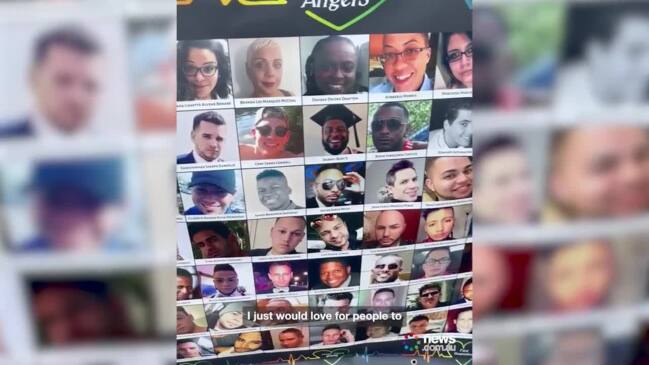

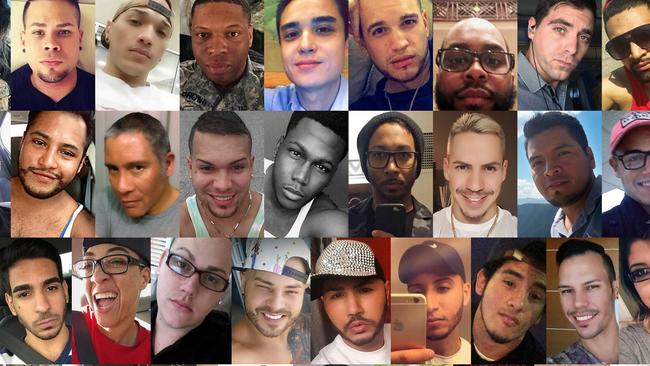

That night 29-year-old terrorist Omar Mateen would murder 49 people in a siege that lasted more than three horrific hours. People like Brenda McCool, 49, a mum and recent cancer survivor; Juan Guerrero, 22, who had only recently told his family he was gay; Luis Vielma, 22, who worked on the Harry Potter ride at the nearby Universal theme park; and partners Simon Carillo and Oscar Aracena who died together.

At the time it was the deadliest mass shooting in US history. That record has since been surpassed as similar incidents continue unabated.

Painful memories of the Pulse shooting were brought back when, just weeks ago, five people were killed at Club Q, a Colorado gay nightclub.

Both Pulse survivors talked to news.com.au about the events of that night in 2016, they said, to keep the memory of the dead alive and shine a light on the depressingly regular occurrence of shootings that continues to blight the US.

In 2022, US mass shootings – including those in a New York supermarket, a Virginia Walmart and a Texas school – have claimed 635 lives, according to the Gun Violence Archive.

“I’m talking because the 49 who died at Pulse can’t,” said Mr Torres.

“And it’s just continuously happening.”

The pair have also shared some of the more confounding aspects of the shooting. Such as the Facebook request Ms Maini received from the murderer before his rampage. And how “polite” the “monster” was, said Mr Torres, seconds before he extinguished people’s lives.

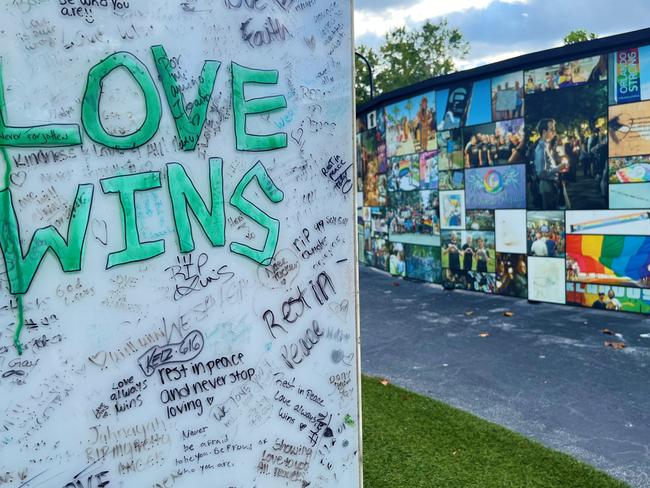

Nightclub remains a shrine

Despite the horror that happened at Pulse, it remains standing to this day.

Located on a busy road, south of Orlando’s downtown, it has a Dunkin’ Donuts and a Wendy’s burger joint for neighbours.

It would be entirely unremarkable were it not for the pictures of the dead, mementos and flags that surround the building.

It’s become a temporary memorial as the club’s owners and the LGBTI community grapple with how to adequately create a permanent monument.

The scars of that night remain vividly clear. A door is marked with bullet holes. One wall shows signs of where the police literally bulldozed their way into the building in a desperate bid to save clubbers.

Upscale bar

It pains Ms Maini, originally from Boston, that Pulse is primarily known as the site of mass murder. It was so much more than that.

“I worked there, from the day we opened in 2004 to the day of the shooting,” she said.

“The owners wanted a gay bar that was upscale with a New York coming to Miami style.”

Several nights a week you’d fine Ms Maini behind the bar.

The favourite cocktail was called a “banana hammock,” slang which roughly translated into Australian vernacular would be “budgie smuggler”.

“We had straights, gays, guys and girls. It was gorgeous, beautiful. A lot of people still say they miss it.”

‘Just another night, until it wasn’t’

That Saturday night was Latin themed, one of Pulse’s busiest.

“There was a great energy. We were packed, everyone dancing, the music was fantastic,” said Ms Maini.

“It was 1.59am; we’d done the last call at 1.45am.

“It was just another great Saturday night.

“Until it wasn’t.”

Mr Torres moved to Orlando in 1988 after a stint as a police officer in New York City.

He would become a promoter of a different Latin night at Pulse.

“I would dress all in white with the white shoes and a fedora hat with my entourage and they would call me ‘Pimp Daddy Orlando’.”

Just before 2am, the friend Mr Torres was with said she needed to use the loo.

As the pair wove through the crowds, Mr Torres briefly stopped to say hello to a friend he had a crush on.

It was the last time he would see him alive.

‘Pop, pop, pop’

At 2.02am Mateen parked a rental car and walked into Pulse with two guns – an assault rifle and a hand gun.

There were still 300 people inside.

It’s still unclear if he had deliberately targeted a gay bar or simply went to the venue with the least security.

“I was in the rest room and all of a sudden I’m hearing pop, pop, pop,” said Mr Torres.

His friend thought it was a sample from a track, but Mr Torres was immediately worried.

“We went into a small stall, laid down on the toilet and put our feet up against the door.

“So if the gunman came in he wouldn’t see our feet.

“It’s my law enforcement instincts,” he said.

“But I never turned down my phone’s volume. That would come back to haunt me.”

‘Never forget the smells and sound’

Ms Maini also heard three pops.

“Juan and I looked at each other and it took a few seconds and then we were like ‘that’s gunshots’.

“The music stopped and it was just shot after shot after shot. Hundreds.

“We slid under a rack where we keep our glasses and I was laying with this kid and we were just holding each other.”

It was then when Ms Maini started screaming her son’s name, only stopping when she was told her she could get them killed.

“I was terrified, thinking to myself ‘is it gonna hurt? Am I gonna be paralysed? Am I gonna get killed’.

“Glasses were breaking, tables were being flipped over, phones going off and people screaming.”

And all the while jaunty disco lights continued to sparkle as people died.

“I’ll never forget that sound and smell. These low moans, like cattle in the distance. And a smell like gunpowder and blood.

“I could hear all these people screaming and crying and I couldn’t help them.”

Killer touched me

The killer would roam the club. At times leaving the dance floor where Ms Maini was and heading to the rest room where Mr Torres was silently perched. Thirteen people would die while attempting to hide in cubicles.

“It was so tragic in there because you could hear what was happening in the cubicle next door,” Mr Torres said.

He overheard the murderer speaking on his phone about his adherence to ISIS terrorism.

“At one point he said (to people in the other cubicle) ‘please do not text anyone’, and I remember thinking he had some audacity coming in shooting, being a monster, and then you’re going to ask people politely not to text?”

Mateen shot into the adjacent cubicle leading a clubber to desperately crawl into Mr Torres’ stall.

Space was so tight that Mr Torres fell off the toilet seat immediately alerting the killer to his presence.

“Because of that gap between the cubicle wall and floor my back was exposed,” he said.

“He walked around and starting touching my rear pants pocket. My heart started pumping. I expected my whole back to be riddled with bullets; that I was going to be a goner.

“Thank God I didn’t twitch or move. He probably assumed that I must have been shot already and died.”

Mr Torres’ phone, which he hadn’t turned to silent, began ringing. His friends, now aware what was unfolding, were calling to see if he was OK.

“I was shitting bricks. In my mind I was saying, ‘please stop calling, you’re jeopardising my life’.”

But the shooter either didn’t notice or assumed it was the phone of a dead clubber.

“I shouldn’t be here but something protected me,” he said.

‘It was a war zone’

Police got to the bar area first and ushered survivors, including Ms Maini, out.

“It was just piles of people and bodies and you’re walking through blood,” she said.

“We went across the street to the Dunkin’ Donuts and I remember turning around and it was just like a war zone with people laid in pick up trucks.

“I helped carry someone and he ended up passing away.”

Mateen had now been hemmed by police into the toilet area where he held survivors hostage. As such, it took far longer for Mr Torres to escape.

Eventually, police used a battering ram to smash right through the bathroom walls.

“A cop jumped into that hole and put a bullet in his head.

“He died there between the two rest rooms”.

Mr Torres was unable to move. A combination of shock and being still for so long meant his limbs wouldn’t respond.

Finally an officer physically pulled him through the wall.

He went to hospital where they removed his bloodied clothes and treated him. A few hours later, dazed and wearing just hospital scrubs, he found himself at a Waffle House restaurant having a surreal breakfast after the carnage.

“My waitress came around, hugged me and took a picture. They were just happy I was alive.”

Almost 50 people were not so lucky.

‘Why is gun control so hard’?

Mr Torres said he’s grateful he spent the entire shooting in a cubicle.

“I didn’t see nothing tragic, so there’s no visual,” he said.

“The only thing I have PTSD is because of the sound, the things I heard in the four walls of the stalls.”

Ms Maini said she was a “little messy there for a bit”.

“It was a dark place. I thought about it 24/7, I would just replay it over and over until one day I decided I couldn’t live like that anymore.”

It didn’t help she was targeted by conspiracy theorists who made false claims the shooting was a set up.

“Horrible humans,” she calls them.

Ms Maini can’t understand the resistance to tougher firearms laws.

“They love their guns here. You bring it up and people get so mad. It’s such an emotional touch point,” she said.

“We’re not even saying take them away but probably we should have background checks.

“Sometimes it’s almost like you’re taking away their kids.”

There was no need for the kind of high powered guns that Mateen used, she said.

“You can’t have a diving board on your pool because it’s too dangerous but my neighbour can have 20 guns next door.

“Why is it so hard?”

Mass shootings like the Uvalde high school massacre and the more recent Club Q shooting brings it all back.

“It’s non-stop,” said Mr Torres. “Non-stop. With Club Q it just all makes it seem like yesterday.”

The argument he hates most by firearms’ fans is that “guns don’t kill, people do”.

“If that was the case, then why don’t we allow grenades to be sold in gun stores? It’s all the same, a mass killing weapon.”

Mr Torres blames social media. He says it turbocharges people’s anger who then want to copy or go one better than the last person – to kill more.

“Social media reaches the weak minded, people that have given up. They’re walking time bombs that are at the point of losing it, of snapping.”

He’s pessimistic anything will change.

“Even if they did take away the guns, they’ll just find another means. It won’t stop the mass killing.”

Eerie Facebook request

Ms Maini says she tries not to think about the killer.

But sometimes she wonders what he was thinking in the hour and a half drive it took him to get to Pulse that night. Why he was so determined to cause bloodshed. Why he never turned back.

She tells news.com.au that Mateen sent her a friend request on Facebook, days before the shooting. And a couple of other people got one too.

“Which was just random. I have no idea why. I didn’t accept it because I obviously didn’t recognise him, but it was so strange.”

Ms Maini still works at gay bars a few nights a week. Her main job is now as a real estate agent with her office just a few blocks from Pulse. She passes the empty building most days.

“I’ve accepted it now. It’s a part of me.”

But some of the impacts of that night linger for longer.

“Everywhere I go, I find myself thinking ‘where would I hide’?

Like Ms Maini, Mr Torres also ensures he has an escape route or hiding spot.

But he heads out; still has fun.

“I say keep dancing Orlando, and keep dancing Club Q.

“Because if we don’t keep dancing, they win.”

On the Pulse sign, which still towers over the now silent club, there is a similar sentiment daubed with a Sharpie.

“To those who rather see us dead than dancing … f**k you.”

Originally published as ‘I shouldn’t be here’: What it’s really like in a mass shooting