How criminal psychologist came face to face with Hoddle St monster Julian Knight

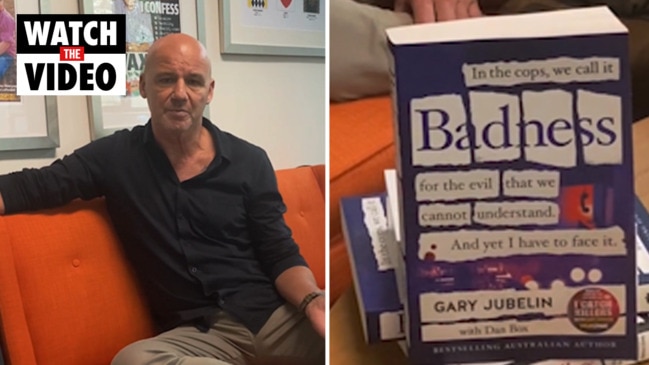

Former homicide detective Gary Jubelin wants to know why people do evil things — here he talks to the man who spent hours up close with Hoddle St murderer Julian Knight.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Tim Watson-Munro, one of the country’s leading criminal psychologists, has seen badness from the inside.

After more than two years working at Paramatta Gaol, Tim left and went into private practice, building up a reputation, particularly his work on behalf of an alleged crook’s defence lawyers, giving evidence about their client’s mind. Among these jobs, there was one that changed him more deeply than anything he’d seen, leading Tim to spiral into darkness.

He was shamed, publicly exposed and had his career taken from him. Tim says he has since had to accept that and find a way back upwards.

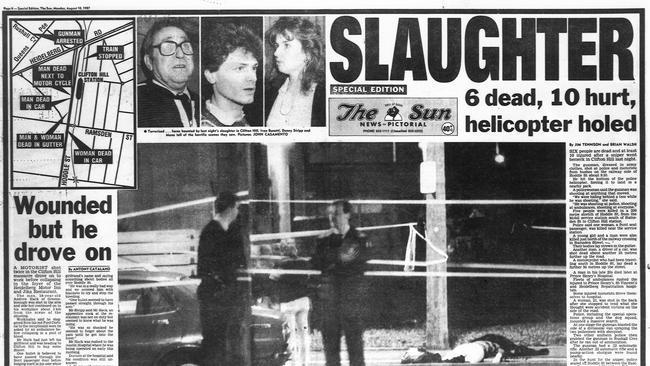

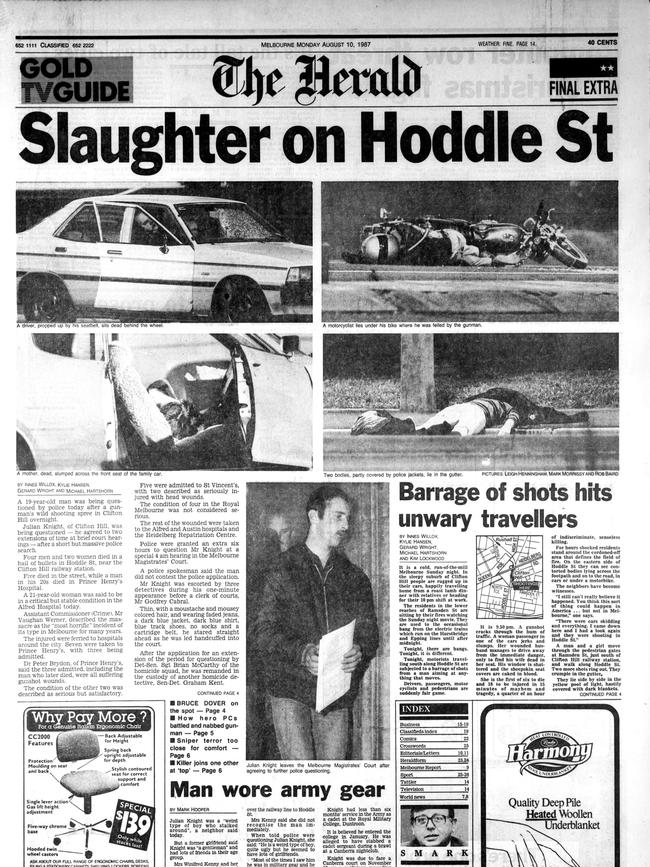

That one job was working with Julian Knight, who carried out the 1987 Hoddle St massacre, killing seven and leaving 19 injured. Tim spent hours talking to Knight in prison, over several months.

It was a pale, cold morning, Tim says, when he arrived at Pentridge Prison in Coburg, north Melbourne, only a few suburbs over from where the massacre happened. The dull bluestone walls and turrets seemed much starker than the warm sandstone Tim remembered from Parramatta and, beyond the heavy gate, was a maze of gates and checkpoints leading him deeper into the shadows.

Tim says he was uncertain, following the prison guard through these. At the time, he was a young husband and father, unsure how much he really wanted to speak with, and possibly help defend, the killer who had destroyed so many families.

Something made him keep on walking, listening to the echo of his footsteps in the prison corridors. Maybe it was the way the killings grabbed international attention, Tim says. The bare facts are that on a Sunday night, 9 August 1987, Knight armed himself with a shotgun and two rifles at his mother’s home in the quiet suburb of Clifton Hill, not far from the centre of Melbourne. One of those rifles was a high-powered M14, similar to those used by the US military. Then Knight walked out of the house and opened fire.

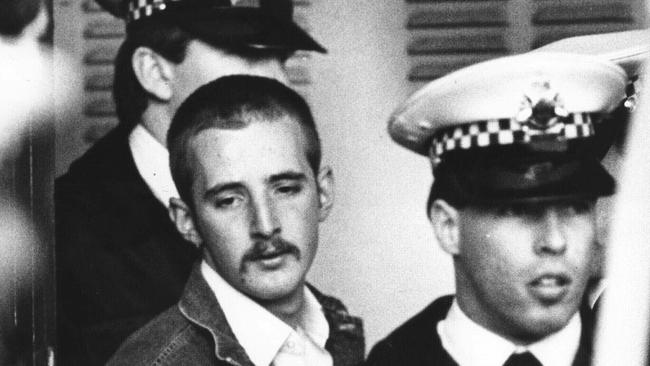

The prison guard who walked with Tim through the corridors that morning didn’t want to understand the killer. To him, the teenager was a mongrel. Just give me five minutes alone with him, he told Tim. There’d be no need for a trial then. Knight might not even make it into court, the guard said.

When they got to the cell door, the guard swung it open and Tim took a step forward. Before coming to the prison, Tim says, he’d sat down to look at all the photographs Knight’s lawyers had provided, taken at the scene of the shooting and the autopsies that were conducted after. In those photos, he had seen what Knight had done.

How his guns shattered the victims’ bodies, their flesh torn and bone slivered into fragments. Tim had insisted that he look at these photos, he says, because he felt a need to understand the killings.

“I was overenthusiastic,” he says now. He was 34 then, “so still comparatively young”.

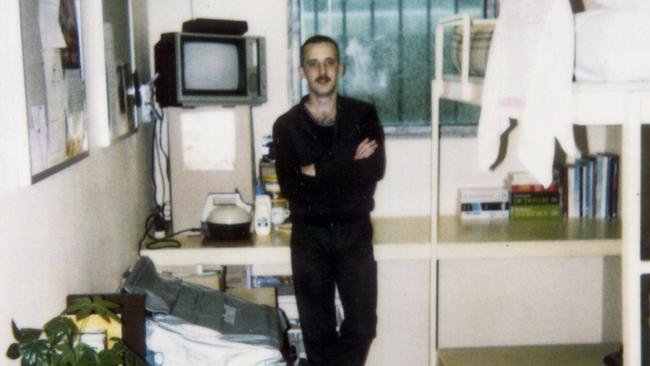

The door clanged shut behind him. Inside the cell, Knight sat on the rubber mat he used as a bed. He looked up. Tim introduced himself and they began talking. Knight was quiet, polite and deferential.

“I was expecting a green-headed monster,” Tim says. “What I actually found was a 19-year-old kid, bewildered.”

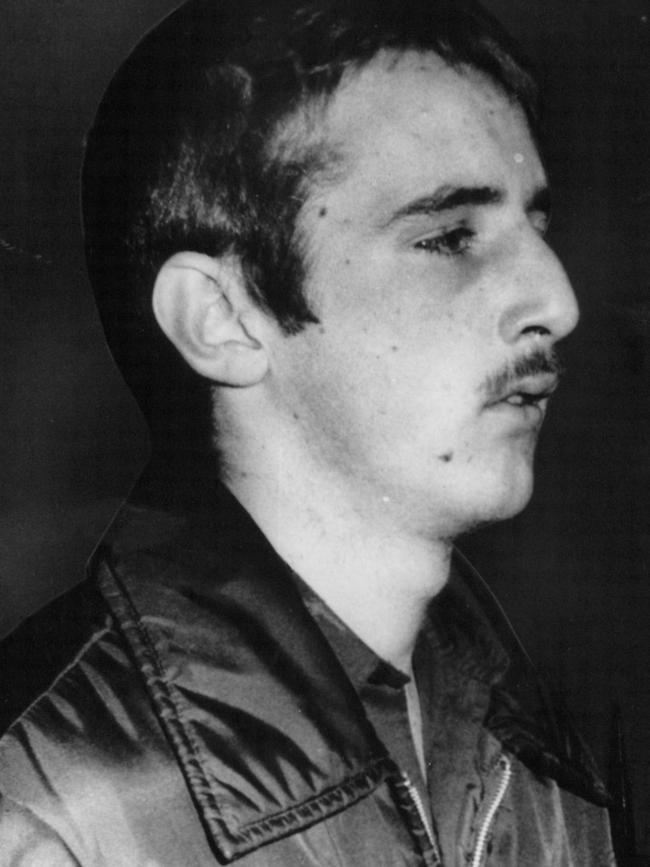

Knight was mouse-like, with a pinched face, narrow moustache and thin, untidy hair. He seemed out of his depth, Tim says, like a child might on his first day of high school. For a moment, Tim even felt compassion for him. Then reality snapped back and he remembered what he’d seen in those photos. The horror Knight had committed.

At first, the two of them talked often as the year passed before Knight’s trial was due to take place, and even as their talks became less frequent they still took place every month. The teenager described how he had been adopted and found out about this at an early age. His adoptive father was an army officer and, as a child, Knight grew up wanting to become a soldier, just like he was. He liked playing with toy soldiers and Tim wondered if these fantasies might be a way of compensating for the loss of control over his own life when he was put up for adoption.

In his mock battles, Knight could be the general. He would have been all-powerful. Everything those toy soldiers did was because Knight controlled them.

Finishing his HSC, Knight’s grades were good enough to get into university but he dropped out after a few weeks. He said that he was lonely. The same year, 1986, Knight enlisted in the army reserve and later wrote about his first parade night, when he got involved in a brawl with some young guys in a street outside the barracks. When one of their brothers came back, looking for revenge, everyone in the barracks’ mess came piling out to defend Knight.

“As it was my first parade night, no one in the unit knew me personally; the fact that I was a member of the unit was reason enough to come to my aid,” Knight wrote later.

Just like in the cadets, here was something he could be a part of.

As the year ended, Knight was accepted into Duntroon Military College, the army’s elite officer training establishment, housed on a sprawling estate at the foot of Mount Pleasant in Canberra.

But Knight had come from a different world from most of the others who arrived there with him, Tim says. Unlike them, he hadn’t gone to one of the country’s leading private schools. He hadn’t had his path smoothed by family connections. While Knight was the adoptive son of a career army officer, his father was not a general or a colonel. And, by his own admission, Knight was immature. He said that he was constantly tormented.

Sitting in the prison cell together, Tim listened to Knight’s stories. The challenge for him was separating the facts of Knight’s humiliations from his perception of them.

The young man seemed unwilling to accept responsibility for his own actions, Tim thought.

“In one AWOL incident I was blamed for convincing two other junior staff cadets to accompany me to McDonald’s,” Knight wrote later. “It was actually their idea and I offered to drive them there after they initially asked to borrow my car.”

Knight said he got a reputation as a troublemaker, an uncouth lout who got into fights, which was also unfair to him.

Tim says he thought Knight had a seething anger, and that the young man might himself have been unaware of how deep this ran.

Listening to Tim, it’s like a light switches on in my mind and I can now see where Knight was heading. Since starting to learn more about badness, I’ve read how, two decades after this mass shooting, a group of US psychologists led by Professor Mark Leary looked at the relationship between aggression and what they called “interpersonal rejection”.

They found that rejection – which seems to run through Knight’s descriptions of being adopted, his parent’s separation, his failed attempts to make a success of himself at school and university, and then again at Duntroon – was “the most significant risk factor for adolescent violence”. That meant there was a stronger link between violence and rejection than gang membership, poverty or drug use.

In July 1987, six months after starting at Duntroon, Knight got into a confrontation with a group of senior cadets in the barracks hallway. Knight claimed that they struck first but only he ended up being confined to the barracks. The next day, a Saturday, he snuck out and went to a Canberra nightclub. He got into another fight with some other cadets and drew a knife, stabbing one of the men and also getting injured himself. Afterwards, Knight was told to leave Duntroon.

In disgrace, he would now face a military court martial. Going back to his mother’s home in Clifton Hill, near Melbourne’s centre, Knight found his old bedroom had been packed up in his absence. His clothes were in boxes. He struggled to pick up the threads of his old friendships, including with a former girlfriend.

Around this time, Knight tried to make contact with his biological mother, without success. Two days before the shooting, Knight found out his old girlfriend was having a party, but he was not invited.

On 9 August 1987, Tim says, Knight had lunch with his mother, his siblings and his grandmother, before driving home in his old Holden Torana. The car was playing up, its clutch went and it kangaroo-hopped along the road.

“It probably represented to him, metaphorically, another failure,” Tim says. “It’s definitely a build-up.”

Knight’s idea that he was being persecuted at Duntroon; the trouble he got into with the stabbing; having no bedroom at home to go back to; the rejection from his friends, his ex-girlfriend and his biological mother. His broken car. Knight would have known that he still faced court martial and, most likely, discharge from the army, Tim says. He was never going to be a real soldier now.

That evening, Knight went to a local hotel and got drunk. Tim says the teenager tried to engage strangers in the bar in conversation. He tried speaking to a barmaid. She ignored him.

“It was that sliding door moment,” Tim says. “What if there’d been people at the pub that he’d had a drink with? If he hadn’t drunk so much? If the car hadn’t broken down? All these what ifs.”

The lesson is that evil is not inevitable; at all these what if moments, somebody might have been able to intervene and stop it. Things might have ended differently. But none of these what ifs happened.

Inside the pub, Knight later claimed, he became convinced the darkened streets outside it had been occupied by a camouflaged militia. They needed to be ambushed. He left the hotel and headed home to get his guns. By that point, he had been overwhelmed by badness.

Inside his mother’s house, Knight had a .22 semiautomatic Ruger rifle, the M14 carbine and a 12-gauge shotgun, all three of them were registered and legally owned. His mum was watching TV elsewhere in the building. Collecting his guns and ammunition, Knight left the house and crossed over Hoddle St, the main road leading through Clifton Hill.

“So he’s just walking out, this angry man?” I ask.

Tim nods. “Walks out with three high-powered weapons and lots of rounds and he just pulled the trigger.”

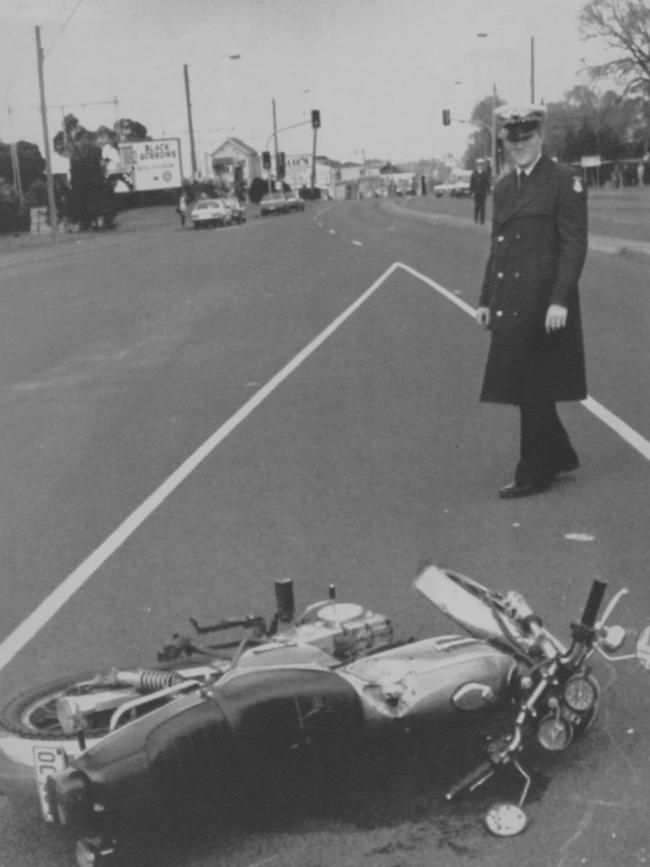

During their conversations in the prison, Knight told Tim he believed that he was in a war zone. One thing that he was good at in the army was target shooting. Knight took up position in a park on the far side of Hoddle St and began to fire on passing cars.

After the first shot, Knight said he couldn’t reload fast enough. He was excited. It was unreal, like he was dreaming. He talked about his victims being pop-up targets and dark figures, rather than being people. One victim was a faceless mannequin with a plastic appearance. Another was a silhouette.

Tim says the different experts who assessed Knight disagreed about whether this was a kind of temporary insanity. One said he was suffering from a personality disorder with hysterical features and could be described as crazy. Another that reality and fantasy were mixed up in his mind. One said it was as if Knight’s military training had taken over. A judge said that he “never grew out of playing soldiers. Instead, he developed a fantasy life.”

“But, you know, he managed to shoot down a police helicopter,” Tim says. Armed cops had flooded the streets in response to the shooting. “It didn’t crash but he hit the tank and they had to come down quickly.” Knight was still a good marksman, Tim says. That, at least, suggests clear thinking.

In the end, he ran low on ammunition. Tim tells me Knight later claimed that he’d planned to keep one round for himself rather than be captured.

“It’s better to die on your feet than live on your knees,” he told police.

The f---ing hypocrite, I think. I have the same words tattooed on my ribcage. I live by them. But, when the end came, Knight surrendered meekly. I’d been expecting more, like Tim had when they first met in prison. I’d been expecting something evil. All there is in Knight is weakness.

Yes, he got rejected. We all get rejected sometimes. But, even after the massacre, Knight went on making the easy decisions – either to give up or to lash out.

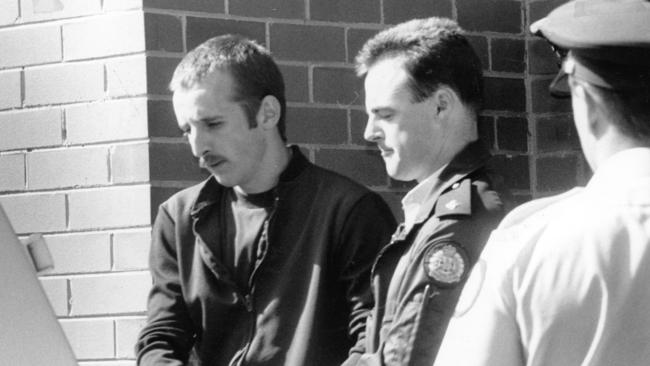

In the end, Knight pleaded guilty to seven counts of murder and 46 counts of attempted murder. That meant there would be no trial and no need for the lawyers to argue publicly over whether he was sane or infected by madness when he carried out the shooting.

At his sentencing in the Supreme Court of Victoria, judge George Hampel said it was, in fact, unnecessary to determine the exact nature of what he called Knight’s “mental aberration”.

“You were not medically or legally insane,” the judge said. Instead, “you had a diagnosable serious personality disorder, a mental condition”.

That difference was important. If all the experts who’d looked at Knight found him to be insane, it would have meant his mind was broken. Knight would not have been responsible for his own actions but instead a prisoner of his fractured thoughts, without free will.

Instead, the judge said, he was sane but with a mental condition. Tim can see me unsure of how to understand this, so simplifies it for me: “It was decided Knight was bad, not mad.”

“Could he justify it in his own mind, his actions?” I ask Tim, wondering about all the conversations he and Knight had together in prison. Surely, Knight must have said something to suggest where he thought the blame lied.

Tim looks straight at me for a moment: “He never directly said, ‘I’m sorry’.”

Badness by Gary Jubelin will be published by HarperCollins on September 5 and is available to pre-order now.

More Coverage

Originally published as How criminal psychologist came face to face with Hoddle St monster Julian Knight