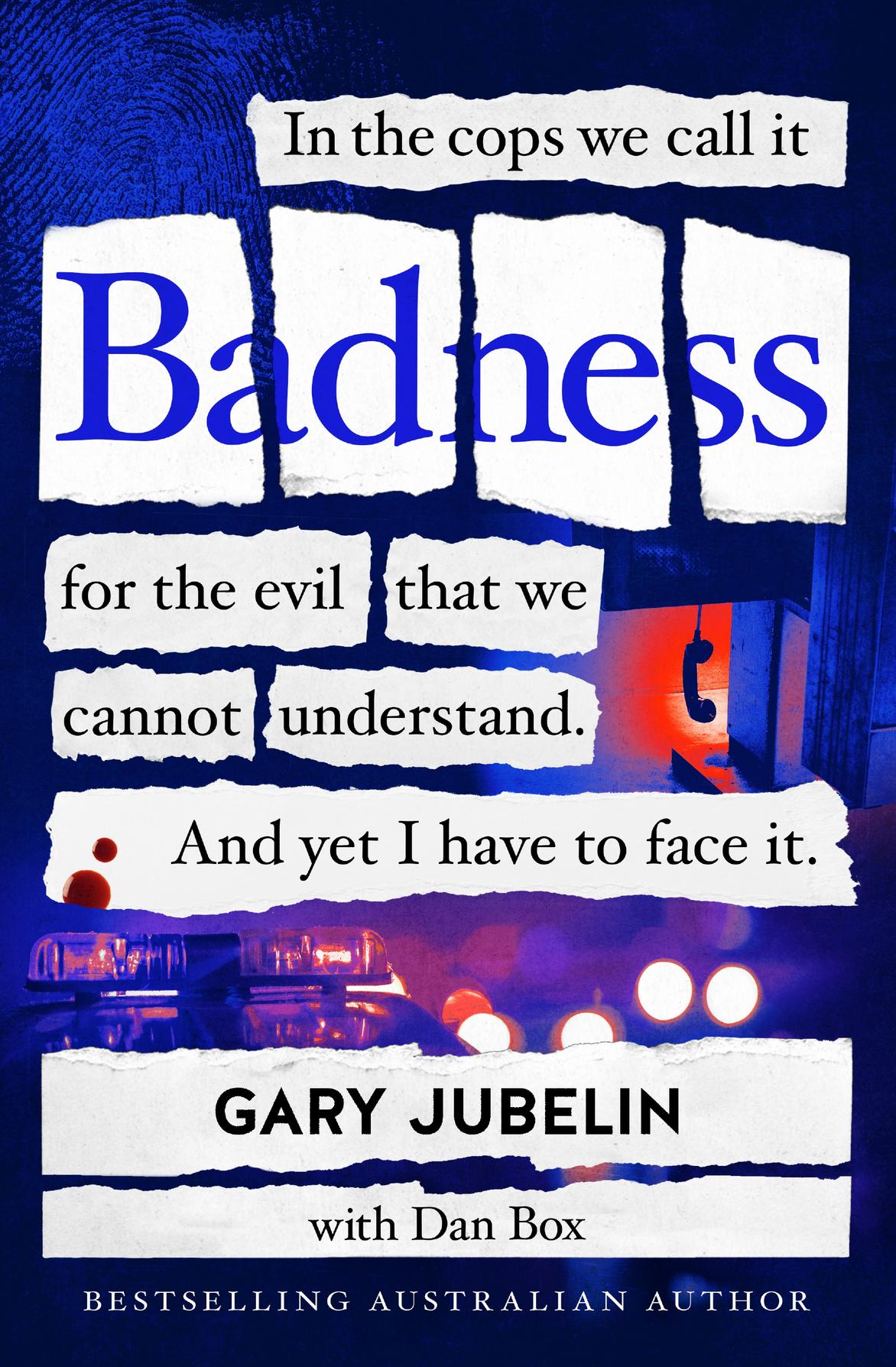

Gary Jubelin ‘Badness’ extract: The day I put the blowtorch on William Tyrrell’s foster parents

Gary Jubelin desperately wanted to find missing boy William Tyrrell. In this edited extract from his new book Badness, he reveals how hard he went after the foster parents.

William Tyrrell had been missing for five months when I took over the investigation in February 2015. The cops had already looked at his foster parents and found no evidence suggesting they were involved in his disappearance but I’d wanted to go in with my eyes open, so we took another look.

Within the strike force, we asked ourselves if they could have murdered William.

Or had him abducted.

Or whether William might have died in an accident and his foster parents somehow covered that up.

We looked at how that might have happened. Could William have fallen from the balcony at his foster grandmother’s house where the family were staying? Maybe his foster mother, who was in the house that morning, panicked. Maybe she decided to hide his body.

I watched the couple closely during our first meeting, when the previous lead investigator took me with him to meet them as part of the handover, and kept watching them over the weeks and months that followed. Again, I could see no evidence of their involvement. But I did see the couple’s grief. I did see their pain.

More than a year later, in May 2016, another detective working on the strike force told me she still had doubts about the foster parents. I listened, partly because I thought she was a good detective, someone I had worked with years before on a murder in southern Sydney and been impressed. Look, she told me, we both know most child murders are carried out by someone who is close to the victim.

Also, William’s foster mother says she was there when he went missing. Her husband says he’d driven into nearby Lakewood, looking for a decent internet signal to make an online video presentation for work, and we’d checked that story out, but he drove back soon after. So we know both of them were at the house that morning.

The detective told me she’d also found inconsistencies in the foster mother’s evidence. Like how she said William was wearing shoes at the time he disappeared. In the last photo of him, taken an hour-and-a-half before the 000 call saying William was missing, he is pictured playing on the front deck, without shoes. There were also the cars William’s foster mother claimed to have seen outside the house that morning, the detective told me.

She’d told police there were two cars parked there, but the cops had found no evidence to back that up. I wasn’t sure. There were no CCTV cameras anywhere on that road, or near it, to show what cars were there or not there that morning. Memories are often unreliable. To me, these didn’t seem to be inconsistencies but more like unanswered questions.

Still, we wanted to be certain. I decided we would call the couple back in and told the detective to prepare interview plans; she and I would go at them once more in the interview room.

Like with everything on that investigation, I reported the decision up the chain of command to my bosses, meaning some of the most senior officers in the police force knew what we were doing, and would know the result. Four months later, in September 2016, we were ready.

THE AMBUSH

The plan was to ambush William’s foster parents.

To see what they might let slip if they were unprepared and exposed. I invited the couple to the police headquarters in Parramatta, Western Sydney, letting them believe they were coming in only to meet some of the detectives for an update on the investigation, as they had done before.

William’s foster mother smiled at me when they got there. We shook hands, then my demeanour changed. “You’re not going to like me today,” I told them.

I was hard, professional.

“I don’t want you talking to each other,” I said. “We’re going straight to Parramatta Police Station.”

I looked at her: “I’m going to interview you first.”

Turning to him: “I’m going to interview you second. You’re not going to get an opportunity to talk between the interviews. You are not going to like me, but maybe you will understand what I am doing. And, at the end of the day, we’ll see where the cards fall.”

We drove them to the police station and I made sure that someone was always with the couple so they couldn’t talk to each other.

Once there, we split them up, showing each to separate rooms.

You could see the shock and upset on their faces.

They felt hurt but that’s just smart policing. You don’t give a potential suspect time to prepare for your questions.

It didn’t matter if they hated me in that moment.

Not if it meant that we found William.

THE CONFRONTATION

Inside the windowless interview room, I told the foster mother that everything she said would be recorded. She was fierce and disbelieving as I started asking questions, tears running down her cheeks, sometimes pale and sometimes flushed with anger.

She wept. I didn’t care.

If we broke either of the couple or made one turn on the other, I’d be happy, but, instead, she had answers.

William could put his own shoes on, she said, when I asked about the photo.

She’d told him to put his shoes on when he went out to play in the garden because there might be bindiis or dog shit out there. She didn’t know if it was bindi season during that visit to her mother’s house or how many of the neighbours kept a dog but all the properties around there were unfenced, so any dog could roam around if it wanted. William knew to put on his shoes.

That sounded plausible, I thought, although I was not finished.

The foster mother was led out of the room and her husband brought in.

LOOKING FOR A CRACK IN STORY

If either of them had done anything to William, I thought he was most likely to crack under this pressure. His wife had always seemed the tougher of the couple and if he himself wasn’t at the house at the moment William was last seen there, then he might have the least to lose.

He repeated what he’d told the police before now; that he got back there around 10.30 that morning.

His wife ran out with one of the neighbours, asking him, ‘Is William with you?’

‘No,’ he said, confused. ‘I just got home, I just got here.’

So why would he have William? ‘Well, where is he?’ his wife asked him. ‘I don’t know,’ he answered. Then he bailed out of the car, leaving everything behind him and started looking, yelling, ‘William? Come out, William. William, where are you?’

From that moment, everything played out in public.

Neighbours helped the couple search. William’s foster mother called the cops at 10.57am, who arrived nine minutes later. That meant if either of them had done anything to William, they had very little time to do it. And, if either the foster mother or her mother, who was also at the house that morning, had done anything criminal, they had very little opportunity to convince her husband to play a part in it.

It’s possible, I thought during that interview with William’s foster father. Maybe your wife and her mother did that. “You know, it has been suggested to me that he might have hurt himself accidentally when they were looking after him, and they have panicked and covered it up,” I told him.

“Never likely. No way. They’d never do that, even if he hurt himself. You’d go straight to the ambulance. Police. They’d never do anything like that.”

“What about … that you came home in the car, and William ran out to see you, and it’s a classic case of a driveway tragedy?”

“Ran him over?” He was in tears.

“Yeah.” I pushed him. “No.”

He looked offended.

He and his wife had thought they could trust me. I kept asking questions. “And another theory, there’s a few of them, that [the foster grandmother] is an elderly lady and she might have done something to accidentally injure William, and [the foster mother] is covering up for

her.”

“No, could not hurt a fly.” He didn’t crack.

When the interview was over, we stayed with the couple, making sure they still could not talk in private. Both wounded.

We led them back to their car, which we’d fitted with a listening device while they were being questioned. Inside it, alone and believing they could speak freely for the first time since arriving at police headquarters, they called me all kinds of names. They hated me in that moment. But then they started to calm down. They said, maybe it was a good thing. That at least I was trying to find their foster son.

THE INQUEST

On the last day of the inquest into William Tyrrell’s disappearance, I sat in court, watching his foster parents present the black-gowned coroner with a book of family photos they had taken of the three-year-old.

The coroner’s face was drawn in a grim line as William’s foster mother, who still could not be named or pictured in public, said the photos were like memories, evidence of her son’s innocence, as well as the love the family had for one another.

There were also fewer police working the case now than when I led it, she told the inquest. She feared the force was losing interest. “No other family member should ever feel the need to fight tooth and nail in order to maintain commitment to find out what happened,” William’s foster mother told the inquest. It was now 19 months since the inquest started and it seemed to be flailing around, trying to find a suspect.

THE ROCK

Sitting in the coroner’s court, it felt like the cops still working on the case looked at me with suspicion. After being taken off the investigation, I’d been told not to be there. William’s foster parents had asked the police

if I could attend it with them, saying they trusted me, despite what had happened.

They told me they’d left telephone messages for the police commissioner, without receiving an answer. In the end they had written to him, saying it was with “profound sadness” that they felt compelled to put in writing their many requests to speak or have him personally respond to their concerns.

In that letter, William’s foster parents called him “our son”, and said he had been the victim of a heinous crime.

“We and William’s birth family are all victims.”

Over the four years of heartbreak since his disappearance, they wrote, I had been their rock, helping give them confidence that the police would leave no stone unturned and would work tirelessly to find the missing boy, “with care and compassion for our son and those of us who have been left behind”.

Badness by Gary Jubelin will be published by HarperCollins on September 7 and is available to pre-order now. For more, listen to Gary’s phenomenally successful I Catch Killers wherever you get your podcasts.