Fifty years ago this Thursday, the unfinished West Gate Bridge collapsed, killing 35 and injuring many. Before the fatal mismanagement of the Covid pandemic this year, it was Victoria’s worst disaster, writes Andrew Rule.

It is 11.50am on October 15, 1970. And it’s too late. A section of bridge deck has buckled, and a desperate effort to correct it by removing bolts and adding heavy concrete weights has turned an expensive and embarrassing engineering mistake into a deadly disaster.

Hundreds of bolts turn blue with stress and snap with a sound one witness likens to machine gun fire.

On the bridge, terrified men hold hands to their ears to block the noise as they see their lives flash before their eyes. Not all will die in the coming seconds — but all fear they will.

One yells, “She’s going down!” A few wildly imagine jumping into the mud flats 50 metres below. Some try to run but can’t escape as the span sags towards the middle and a gash opens along the central join. A few men fall into the hollow space inside.

One man, Charlie Sant, feels death is inevitable so he sits on a box and waits, as if in a trance. Somehow, he rides the falling bridge and escapes with a broken leg and ribs.

Vincent Rosewarne falls into a piece of springy wire mesh that breaks his fall, leaving him with a broken nose, two broken arms and fractured leg.

John Thwaites grabs a girder and holds it all the way down. He gets two black eyes.

On the ground below, their mates who have descended early for lunch are in huts built under the “safety” of the doomed span. Many are killed.

Across the river in Port Melbourne, a 10-year-old schoolboy, Udo Rockmann, is focusing his father’s camera on a seagull when he hears 2000 tonnes of steel and concrete crash to earth. He pans sideways and snaps the moment as mud sprays hundreds of metres and dust billows from the smoking wreckage.

Udo will later join the navy and become a renowned electronics engineer. He still has that old Agfa camera and says he has never forgotten the lesson learned that day: for engineers, the price of taking shortcuts is disaster.

Bad news travels fast. At 11.51am the first wave of telephone calls signal the unthinkable.

At ambulance headquarters in the city a red light blinks on the switchboard. When the operator answers, a stressed voice blurts: “She’s gone! The bridge has gone!”

At the Herald building in Flinders St, a teenager starting his first week as a “copy boy” picks up a jangling telephone on the picture editor’s desk.

“The West Gate Bridge has just fallen down,” yells the caller.

The new boy, Colin Bull, isn’t falling for the stupid practical jokes people play on rookies.

“Bullshit,” he snaps and hangs up. Immediately, it rings again. A different voice, same panicked message. It’s no joke. Young Bull runs to the editorial conference to interrupt his new boss, who’s listing pictures to go with the day’s routine stories.

Meanwhile, at the police communications division, the incoming message is clear: “Disaster at West Gate. West side. Span collapsed. Send all services.”

But someone at police headquarters is wary of creating panic or encouraging sightseers. Police reporters who work from a grubby pair of offices at Russell St hear a strangely neutral message on their radio scanners, stating there is “an industrial accident in Spotswood.”

Cadet reporter Bruce Matthews gets into the police rounds car with another reporter, while others stay back to play cards. It seems like a routine job until they are half way across the Dynon flats to Footscray and the two-way radio crackles to life.

The chief of staff breaks the news — and tells them to step on it.

Their driver “Bushfire” Dwyer turns left and speeds through Yarraville. The unfinished bridge looms ahead, but looks shockingly wrong.

“It looked like an aircraft carrier with its back broken,” Matthews will recall half a century later.

Matthews is 20 but isn’t the youngest reporter there. That is Paul Kerr, diverted a few minutes earlier with a photographer assigned to a picture story at Essendon Airport. Kerr, just 17, and Matthews start dictating ragged bursts of copy into two-way radios to update bulletins compiled at their respective news rooms.

It is a brutal baptism. The two youngsters describe scenes they never quite forget, no matter how much they want to.

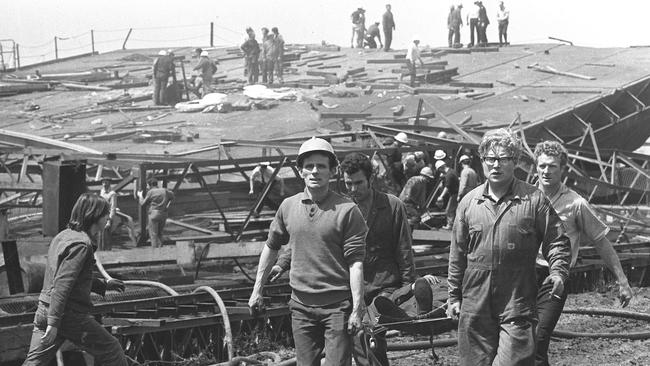

It is like the aftermath of a bombing raid: beneath the smashed bridge span are dead and injured men in the mud and the blood and the fear.

Matthews is numbed. He talks to survivors propped against the fence. When one lapses into a coma he moves to the next.

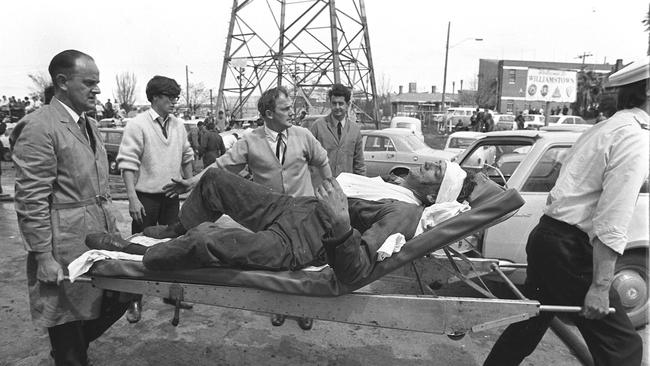

A total of 35 men are dead and 18 are injured, some terribly. Others have miraculous escapes that condemn them to nightmares for as long as they live. Which, for some, is not long.

Section engineer Bill Tracy dies three weeks after the crash without regaining consciousness. Rigger Frank Piermarini says he was spared by “the grace of God.” He dies within a few weeks.

Desmond Gibson is one who dived into the gash torn in the deck — tumbling the hollow space inside the span, where he’s thrown around like a ping pong ball. He survives the fall but, aged 29, will turn grey within months and die of his fourth heart attack in three years, killed as surely as his mates were.

There are miracles, too. Some men are thrown into the water and survive. Ed Halsall, walking below the falling bridge, hears it and runs. The wind blast created in the split second before the span hits the ground blows him off his feet and throws him clear, physically uninjured but traumatised beyond words.

Besides the dead and the maimed are the walking wounded. The survivors help search for the missing, men speared into the river or the stinking black mud.

“Death wore a muddy face,” writes the great journalist Bruce Wilson in this newspaper’s forebear, the Sun News-Pictorial. “Death was a mangled and twisted thing … ”

Every tragedy is tied to a love story. No family’s loss is worse than another but some touch a stranger’s heart a lifetime later.

The youngest worker killed is Cyril Carmichael, just 19, who was all set to announce his engagement to his girlfriend Glenys Fone. Jouzaf Ozelis, 23, was getting married to Regina Buzinkas. Bob West, 24, and his wife Pat had three little kids and one on the way.

Searchers find 32 bodies the first day, three more later. Bernard Butters’ family waits eight days for his body to float to the surface after debris is moved.

John Doody, 20, teased on the job as a “long haired larrikin”, refuses to stop when the ambulance and fire brigade move in. He digs in the mud for his injured mates and carries out bodies until he collapses and is sent home. He comes back an hour later.

Every day for weeks, a woman stands at the mesh fence and stares at the twisted pile that killed the man she loved.

Before the dead are buried, the blame starts. By the time the hastily-appointed Royal Commission starts sitting two weeks later, accusations fly.

Workers and their unions point out they had raised safety fears for months. But what’s at fault: flawed design, shoddy work, or a lethal combination of both?

The bridge designers, the British firm Freeman, Fox and Partners, fly in experts notably absent in the two years since construction began. Their main adversary is John Holland, the contractors responsible for building the bridge to the Freeman Fox plans.

The designers and builders blame each other. There is evidence to support both sides. But it’s clear there were troubling signs about the design all along.

More than any other structure, a bridge has to resist gravity. Which is why, since pre-Biblical times, bridges were built using arches to ensure strength. Even something as relatively modern as the Sydney Harbour Bridge is arched. Suspension bridges like San Francisco’s Golden Gate get their strength from the massive swooping cables from which the deck is suspended.

But the West Gate is an ambitious example of the latest bridge building fashion, the hollow box girder type — sleek and futuristic, but looking as if there is little to support flat horizontal spans but their own internal strength. One critic likens this to standing with arms outstretched, resisting the brutal leverage of gravity.

It turns out that the design has “form”. Ominously, a similar bridge collapsed during construction at Milford Haven in Wales, killing four men, four months before the West Gate disaster.

Experts try to play down the striking fact that both fatal failures are of part-built bridges of Freeman Fox’s box girder design.

The more the critics look, the more problems they find with the new bridges. A bridge over the Danube in Vienna failed badly in 1969. And after West Gate, a bridge over the Rhine collapses and kills five men. If there is no in-built weakness then why the rush to strengthen new box girder bridges all over the world?

In fact, after the Wales tragedy, the Lower Yarra Crossing Authority responsible for West Gate had ordered extra steel framework as a precaution regarded (except by rightly cautious construction unions) as an overcautious “belt-and-braces” approach.

Even earlier, in March 1970, the Deputy Opposition leader Frank Wilkes told parliament that workers had walked off the bridge because of a sagging span they considered dangerous. Wilkes’ warning was ignored in parliament and ridiculed as “rubbish” by Rupert Vian, executive officer of the Lower Yarra Crossing Authority.

Why was Vian so strident? It seems he was desperate to maintain public confidence in the face of simmering industrial trouble, conflict between designers and contractors, and insiders’ doubts about the design’s safety.

Three weeks before the crash, a local newspaper photographer taking publicity shots on the bridge saw an obvious buckle in the decking and was warned against photographing it. He claimed a foreman told him it would be covered with bitumen and no one would know the difference.

The photographer snapped the picture when no one was looking. After the crash it was published in a newspaper alongside a signed statement by the man who took it.

The picture captured the story that the three-man Royal Commission took 300 pages and eight months to produce on July 14, 1971.

Among the thousands of words was a sentence that the architects of the present hotel quarantine disaster might ponder: “Error begat error … and the events which led to the disaster moved with the inevitability of a Greek tragedy.”

READ MORE:

MYSTERIOUS GANGLAND MURDER THAT ENDED SUNSHINE BOYS

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout