Andrew Rule: Murder that marked beginning of end for Sunshine Boys

The Sunshine Boys were killers and drug dealers that liked Tarantino movies and had a taste for their own product. Andrew Rule explains why the murder that marked their downfall remains a mystery 20 years on.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Dino Dibra was shot dead outside his house on a Saturday night 20 years ago. It was the beginning of the end of the deadly western suburbs gang known as the Sunshine Boys.

Two decades later, nobody knows any more about the murder than they knew that night: two masked men ambushed Dibra outside his house in Krambruk St, Sunshine West, hitting him with multiple shots from two weapons.

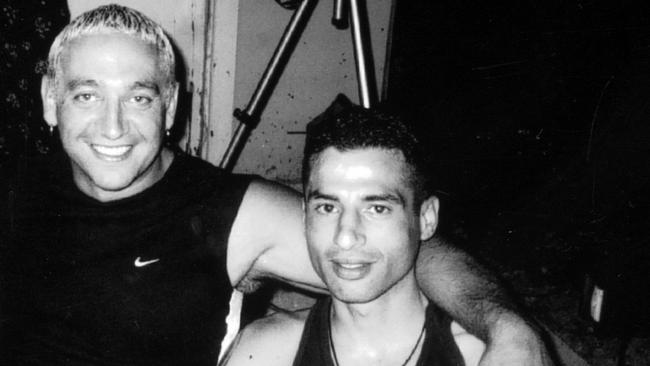

Within days, the police’s working theory was that the killers were Dibra’s boyhood mates, Andrew “Benji” Veniamin and Paul “PK” Kallipolitis.

It was a reasonable conclusion. Both were killers with a breathtaking capacity for treachery that would lead them and others to early graves. Veniamin loved Tag, his “staffy” cross, but he loved guns more. He was a killer before cops could spell his name.

There was no firm evidence, so the assertion that Veniamin and Kallipolitis had the motive and means to do the Dibra hit firmed with every retelling. Maybe that was the perfect “smother” for a tough old crook who told his lawyer he’d had Dibra killed.

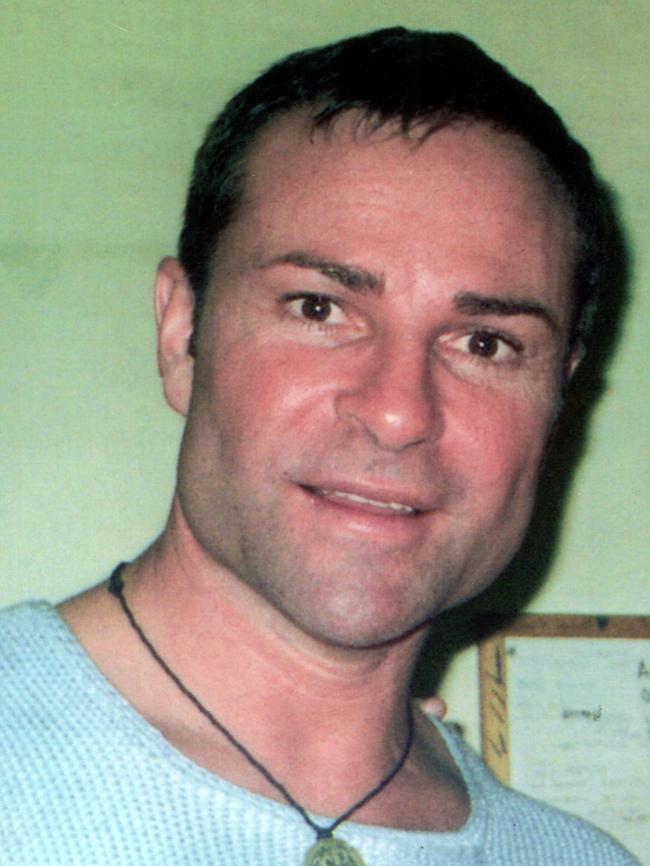

His name was Lewis Moran and he, too, would end up shot dead. He was a cunning and sometimes violent criminal but never a “big noter”.

Moran described his former de facto wife Judy Moran, mother of Jason and Mark, as “an imbecile” for courting publicity. He knew Jason was spoilt and suspected he was psychopathic, the assessment of a father who had graduated from pickpocket, burglar and standover man to drug dealer, race fixer and briber of police.

But family is family. And Lewis Moran had brought up Jason’s older half-brother Mark as his own. Mark’s natural father was his mate, gunman Johnny “Handsome Harry” Cole, shot dead in Sydney in 1982 while working for Harbour City mobster Frederick “Paddles” Anderson.

When Mark was killed outside his house in Aberfeldie on June 15, 2000, Lewis took it hard. But he never believed Carl Williams had done it, as police suspected for a long time. While the baby-faced Williams was easy to under-estimate, he tended to pay others to do his dirty work.

Moran was sure Dibra was closely involved in killing his stepson, so it made sense that Dibra’s execution exactly four months later might have been his revenge.

He certainly put it that way to his longtime lawyer Andrew Fraser, telling him Carl Williams didn’t have the grit to shoot Mark personally and that Dibra was behind it.

Williams was charged over Mark Moran’s death but the charge was dropped after investigator Ron Iddles concluded he could not have got to the murder scene in time (from where he was provably in Gisborne) without a helicopter.

Williams’ alibi was good enough. Dibra’s and his mate Rocco Arico’s were too good by half.

Dibra had an appointment with the homicide squad that exact evening to discuss suspicions that he and Arico were the last to see “Mad Richard” Mladenich alive the month before.

As alibis go, being with the homicide squad when a murder occurs takes some beating. Amazingly, Arico was buying new clothes at the same time, so his alibi was watertight, too.

When Lewis Moran heard of Dibra’s elaborate alibi, he interpreted it as proof Dibra was behind Mark’s death. Moran told Fraser that Dibra was killed as payback. He didn’t go into details. He might well have meant he’d paid others to do the job. If so, one of the masked shooters might well have been Veniamin, who was always “willing” if the money was right. And he had his own reasons to turn on Dibra.

Although the Morans were by this time referred to as part of the Carlton Crew, Lewis came from a time when painters and dockers ran the Melbourne underworld with the motto “We catch and kill our own.”

Like his allies, the Kane brothers, Moran did not imitate television gangsters the way the Sunshine crew did. All his life, Moran sen. had avoided “red lighting” himself.

The difference between old school Irish-Australian crooks like Moran and upstarts like Dibra and his “mates” Kallipolitis and Veniamin was that the new boys attracted publicity with insane violence that would inevitably lead to jail or the morgue.

Dibra told a reporter outside Melbourne Magistrates Court in August, 2000: “Mate, I’ve just watched Reservoir Dogs too many times.” He was dead two months later.

In truth, the Sunshine boys always had the potential to exterminate each other in the dog-eat-dog world of drug dealing, “grow” houses and “chop shops”.

For a start, the gang members were almost all from different ethnic groups, and so the alliances formed on the street could swiftly degenerate into internal warfare at the first sign of big dollars or a little “disrespect”.

Before they turned on each other, they turned on outsiders — even innocent citizens who happened to enrage them.

The anti-social behaviour started early. The young Dibra, Veniamin, Kallipolitis and their mate Michael Dewhirst would hoon around on motorcycles to bait police into pursuits.

It was not long before they were feared by ordinary citizens in their patch of the western suburbs. Beyond that, they were hardly known. Even in the late 1990s, as their criminal activities expanded, crime squads were largely ignorant of them.

Their early criminal enterprises were hydroponic cannabis crop houses. That brought them into contact with another budding criminal who was graduating from stealing video recorders to dealing drugs. His name was Carl Williams. He decided he could use the tearaways to run drugs, collect debts and intimidate rivals.

As they started to use more of the drugs they trafficked around Melbourne nightclubs — and sometimes interstate — the Sunshine crew grew more erratic.

Dibra was present when one of them opened fire on a bouncer at the Dome nightclub in Prahran in 1998, the same year he was suspected of ambushing drug dealer “Mad Charlie” Hegyalji, who was shot dead as he arrived at his Caulfield home late at night.

Dibra was a regular in the King St nightclubs, mixing business and pleasure by dealing drugs and entertaining strippers. He and his mates took other people’s cars at will. No one was keen to report them to police.

Dibra and Arico’s team were so crazed that while under surveillance over the Dome shooting, they pulled a brazen abduction in daylight, forcing a man into the boot of a hire car in Sunshine.

The victim opened the boot from inside using an emergency lever and ran off down a busy street, only to be caught and forced back in the boot in front of horrified witnesses. They took the man to a “safe house” that was, fortunately, fitted with listening devices.

They punched, kicked, pistol-whipped and threatened him with a knife, the whole ordeal recorded by police. They quickly lowered their demand for $20,000 from the victim’s family to $5000. Apart from the extreme violence, it was farcical.

Back then, young Arico was keen to impress Dibra. He boasted: “Hey, if I’d have known he’s only gonna get five grand, I would have put one in when he tried to jump out of the car.”

When Dibra tells him this is crazy talk, Arico retorts: “I would have just went f---ing whack. Cop this slug for now. I would have slapped one in and I would have said ‘Hold onto that for a while, don’t give it to anyone and jump in the coffin’.”

As Dibra admitted, they were gangster film fans. His bedroom walls were covered with posters from The Godfather, Scarface and Goodfellas.

But real life was harder than the celluloid sort. Inevitably, the mixture of guns, drugs and testosterone meant that when friends fell out, they often didn’t get up.

Ironically, Arico’s crazy streak probably saved his life. In July, 2000, a month after the Moran hit, Arico shot a driver repeatedly in a road rage confrontation after cutting him off at a roundabout in Taylors Lakes. Two days later he and Williams were arrested at the airport with a lot of cocaine. He beat the trafficking charge but served seven years for five bullets he put into the motorist, who survived.

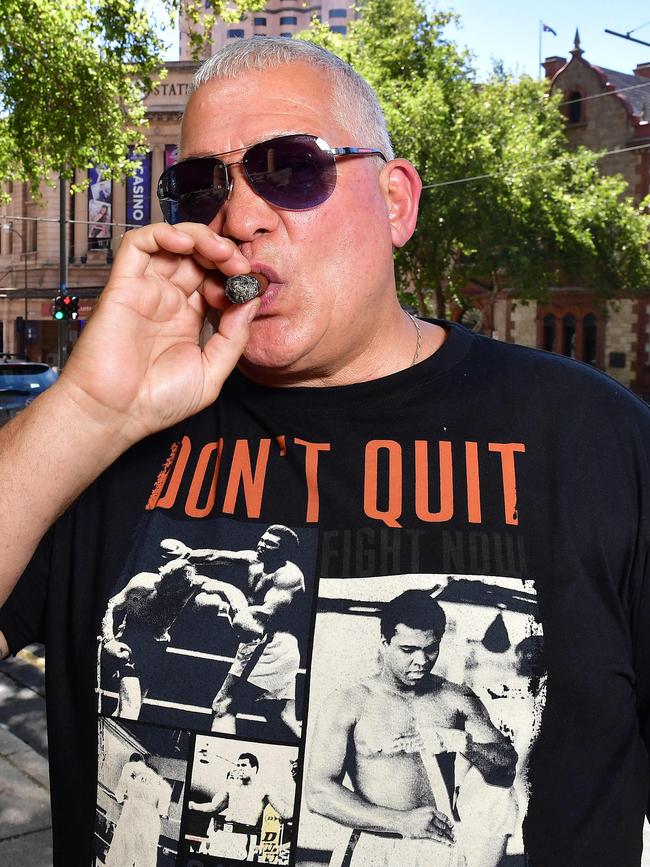

By the time Arico was released, the Sunshine boys were dead or gone. Older and slightly wiser, Arico graduated to be a drug dealer posing as a property developer. He was living in a Brighton mansion before returning to jail in 2017, sentenced to a minimum nine years for extortion, drug trafficking and violence.

Arico is the only member of the crew to get past his 32nd birthday. He is also certain to be deported to Italy, land of his birth, when he is released. One-time friend Carl Williams was not so lucky after his jailhouse execution, reputedly with Arico’s prior knowledge.

Outside or inside, there are always killers for hire. Andrew Veniamin had a homicidal streak that meant he would kill anyone for money, much like Chris “Rentakill” Flannery, eradicated in Sydney in 1985 by fellow crooks because he was so dangerous to everyone. Veniamin was shot dead in a famous case of self defence by Carlton identity Mick Gatto, who testified the little man pulled a pistol on him.

Whether “Benji” did try to shoot Gatto or not, he had it coming.

Investigators believe that the night Dibra was shot, Paul Kallipolitis was in the house and would have been killed, too, if he hadn’t jumped out a window. “PK” was murdered later, almost certainly by Veniamin.

When drug dealer Mark Mallia was tortured with a soldering iron and killed over a drug debt in August 2003, it was clear that Veniamin was one of the four people Carl Williams had paid to do the unspeakable crime.

Mallia’s burnt body was found in a wheelie bin dumped in a drain at the Sunshine West soccer ground. The same place the killers would have kicked a ball around as kids, back when their parents were sure they had brought them to a better life in a young country.

READ MORE