Andrew Rule: Cold cases prove even stone cold killers drop hints

It is a rare offender who can keep a secret so tightly for decades that no one gets a whiff of it. And police are hoping for that whiff with the reward for information in the case of Thomas Cooper, the 18-year-old plumber shot by the “Cowboy killer” in 1980.

The odds are the killer is still alive — the police must think so, or they wouldn’t have pressed for a million dollar reward for a murder from 40 years ago.

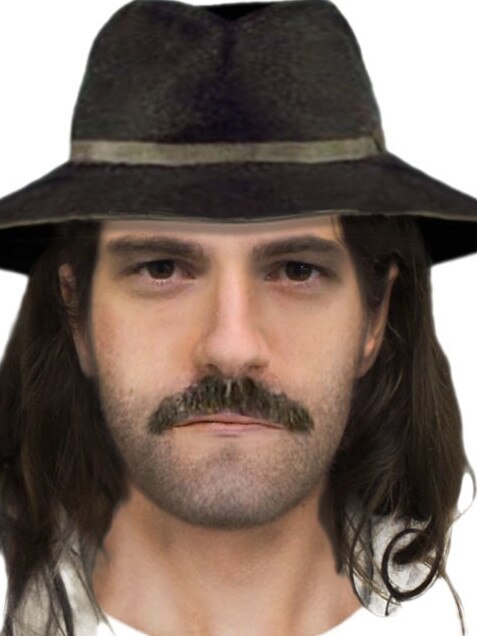

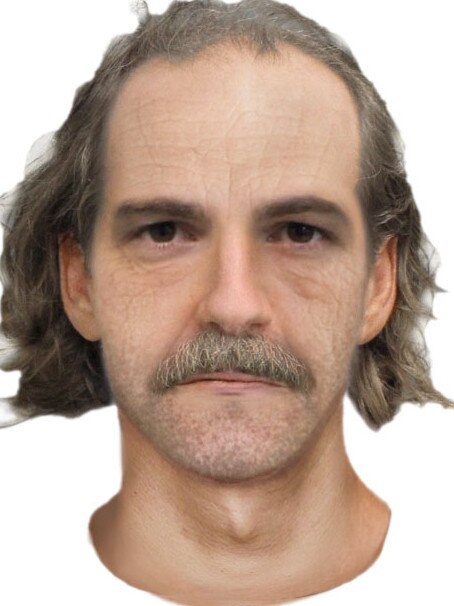

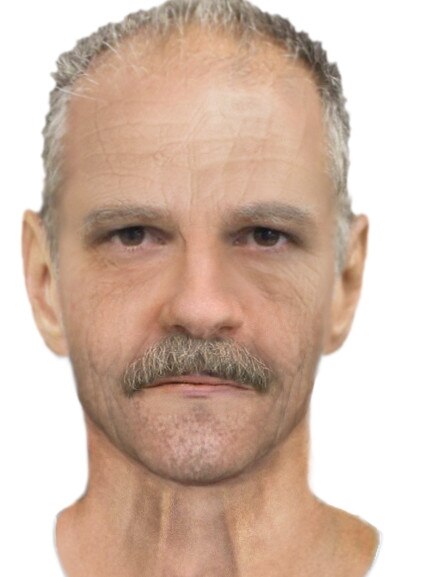

It happened on a winter evening in 1980, in a carpark at Ricketts Point, Beaumaris. A man in a broadbrimmed hat shot teenage plumber Thomas Cooper, who was parked in his Holden with his girlfriend.

The big hat, moustache and rifle glimpsed by the terrified girl led to “Cowboy killer” headlines — but not to the shooter.

He probably ditched the hat within seconds and the rifle and moustache soon after, leaving investigators to chase an unknown male with nothing to distinguish him from a million others.

All that’s known of the killer is that after dark on August 18, 1980 he wore a hat — more likely an old army hat or tourist souvenir than a real “cowboy” model — and took a .22 rifle to Ricketts Point.

Whether he was peering randomly into cars in the “lovers’ lane” or was obsessed with Cooper or the girlfriend was unknown. The girl did not recognise him in the moment after he broke a side window. It was dark and the hat shaded his face as he probably meant it to.

As Cooper tried to drive off, the man shot him three times, after which the quick-thinking girl steered with one hand and pressed her dying boyfriend’s leg on the accelerator with the other.

The hat and moustache must have seemed like a good description. But they didn’t identify the shooter and actually blurred the picture: decades later, the lingering image of the “cowboy killer” is of a High Noon character, not the likely reality of some pot-bellied pensioner with a terrible secret.

The hope now is that the reward announced this week might loosen tongues. If dollars do produce a lead, it probably won’t be about hats but about something the killer has let slip in a moment of boastfulness or remorse.

It is a rare offender who can keep a secret so tightly for decades that no one gets a whiff of it. Even stone killers can drop hints.

That’s what happened in the case of the deviate who ultimately became so well-known as “Mr Stinky” that it overshadowed better clues to the identity of the man who got away with abducting and murdering teenagers Garry Heywood and Abina Madill near Shepparton in 1966.

Police were so keen to believe that Abina’s boyfriend did it that they ignored key clues, such as the fact the killer used a Mossberg rifle bought a few years earlier in a nearby town.

It was 16 years before another generation of police found that the killer was the same man committing a string of rapes in Melbourne’s outer east in the 1970s.

The breakthrough was a flash of genius by a fingerprint expert who in 1982 matched the 1970s suburban rapist with the 1960s Shepparton killer.

But nobody knew who it was for another three years.

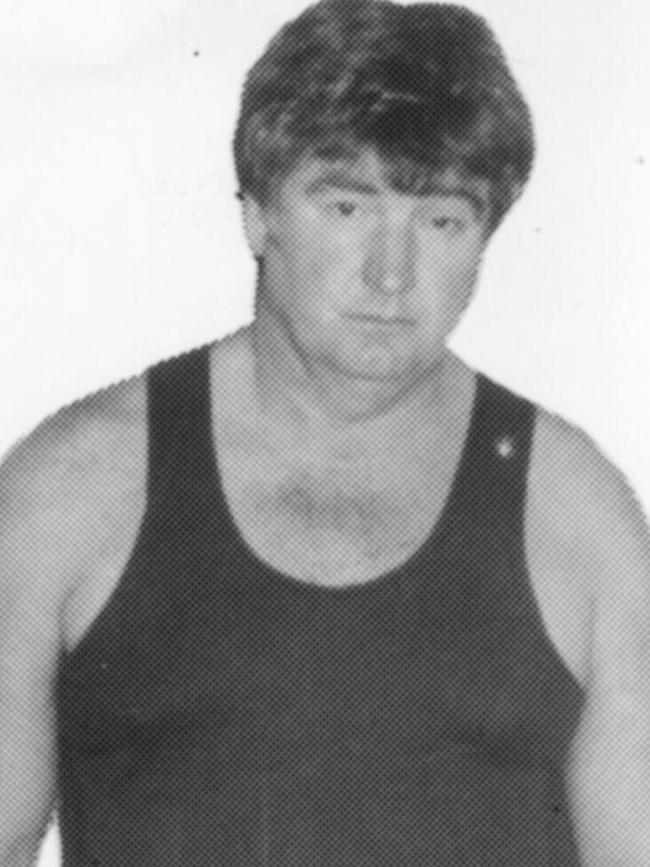

Raymond Edmunds finally blundered into the net when routinely fingerprinted for indecent exposure in Albury in 1985. His subsequent arrest for rape and murder was not a total shock for those who knew him best.

Edmunds’ first wife, who’d fled from his bizarre and violent behaviour, had once screamed: “You’re sick, you bastard … you probably killed those two kids at Shepparton!”

That was only four months after the murders.

Nine years later, in 1975, Edmunds was with a dairy farm owner, Don Miriklis, when a troublesome tenant they were evicting from a farmhouse started yelling abuse.

Miriklis never forgot how Edmunds turned on the tenant and grated: “Back off, or I’ll get a gun and blow your head off … I’ve done it before.”

When Edmunds was finally arrested, Miriklis recalled the threat word for word.

He wasn’t the only one with a story about the man who once beat a cow to death with a shovel.

One reason Edmunds was invisible so long was because of shoddy early police work, red herrings and publicity that amplified irrelevant detail and mistaken “expert” assumptions.

A sculptor made a bust that was so generic it was more hindrance than help. But that wasn’t as bad as a psychiatrist’s advice that the killer was the son of a British immigrant, collected coins and stamps, liked cricket and “has been to the Opera.” All wrong.

Police, relying on what two out of 10 witnesses suggested, said the killer’s voice was a “cultured Scottish or Northern English accent.” It wasn’t.

And the smell? Fewer than half the victims said the rapist had a distinctive odour but this was reported as a “foul” smell.

When a Sunday newspaper coined the name “Mr Stinky” it took off, a catchy label that obscured the real clues: the rapist was usually barefoot and carried a long butcher’s knife.

Assumptions turned into “facts” that swamped the investigation with false leads for more than two years. Until the day Edmunds trapped himself when he was caught “flashing.”

In the end, dumb luck trumped the painstaking elimination that should have nailed Edmunds eventually. Then again, maybe it wouldn’t. Because the oldest and coldest cases are inevitably overtaken by the need to solve fresher ones.

False leads and shaky assumptions have crippled other investigations, too.

The dead ends are many, but two standouts are the Tapp double murder at Ferntree Gully in 1984, and the Antje Bartkowiak hit in St Albans in 1981.

When nurse Margaret Tapp and her young daughter Seana were found strangled in bed in August 1984, detectives looked hard at those who knew them best.

By the time they had eliminated the usual suspects, it was hard to trace a dozen other potential candidates.

Police aimed at the widow of a doctor who had been one of Margaret Tapp’s lovers, but did not track all the other doctors she’d known — including one notorious GP often visiting the suburban hospital where she worked. The same GP later convicted of child sex offences.

The dirty doctor is still out there.

So is the hitman who shot Antje Bartkowiak in a St Albans house in 1981.

One reason for that case going nowhere might be that, despite the victim having fatal .357 pistol wounds, the then head of the CIB, Phil “Fat Harry” Bennett, dismissed the shooting as burglary gone wrong.

Whether this was stupidity or something else, it stunned Antje’s family — and the dedicated detectives who traced a bank manager who recalled a troubling conversation with the dead woman’s estranged partner before the murder.

While discussing whether Antje would pursue her claim for a house they jointly owned, the client had snapped at the bank manager that she would not dare or he would “get” her.

It always was a better lead than burglary gone wrong — but it went nowhere for 35 years.

Of course, police aren’t the only ones to chase wrong leads.

Matthew Johnson, serving life for killing Carl Williams, tells friends he is outraged by a story repeated in this column months ago that he was indecently assaulted as a young prisoner. He says it’s completely false and, after some digging, we’re willing to take his word that it never happened.

READ MORE:

MATTHEW WALES ‘POOR RICH BOY’ IN LONELY PRISON LIFE

UNPICKING LINGERING BIGOTRY AGAINST THE CHAMBERLAINS