French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston set to open after Melbourne lockdown

Every picture in this blockbuster exhibition of Impressionist works ‘is better than the one before’ — and the good news is they are right here on our doorstep.

Arts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Arts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s an unforgettably romantic scene that Australians can only dream about in these days of Covid-19. A young couple twirls at an open-air cafe in suburban Paris, the swish of the woman’s dress still almost audible 138 years after it was frozen in time.

The snappily-dressed man’s intentions seem clear, but his pretty companion half-turns from him. It is diffidence, modesty or something else? She appears to be wearing a wedding ring. Is the man in blue her husband?

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s painting Dance At Bougival, 1883, still casts a spell in 2021. Imposing and impressive at almost 2m tall, the picture usually hangs on the walls of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which purchased the work for $US150,000 in 1937.

Dance At Bougival is firmly entrenched as a “destination painting”, according to MFA Boston’s head of paintings conservation Rhona MacBeth. It’s a work of art so special that travellers specifically go to Boston to see it.

Well, they won’t get to see it there for a while, because Dance At Bougival is right here in Australia.

The painting is scheduled to go on view from next week at the National Gallery Of Victoria, Covid-19 willing, where it’s bound to be a public favourite in Melbourne’s blockbuster international exclusive exhibition French Impressionism From The Museum Of Fine Arts, Boston (June 4 to October 3).

Of the 99 paintings in the exhibition, an astonishing 79 have never come to Australia before. They’re beauties, and Dance At Bougival is one of many highlights.

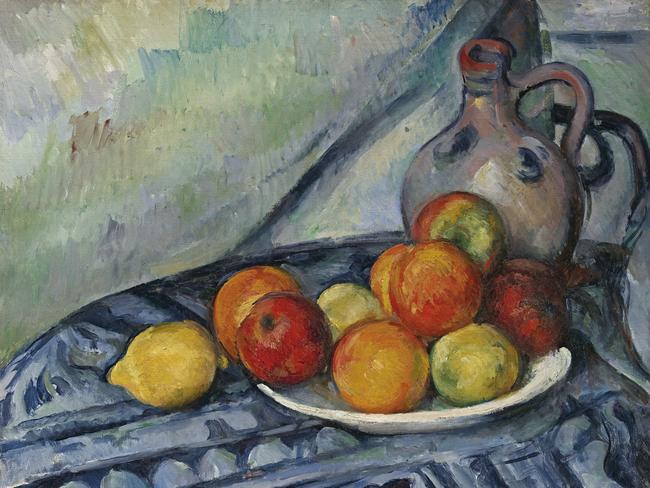

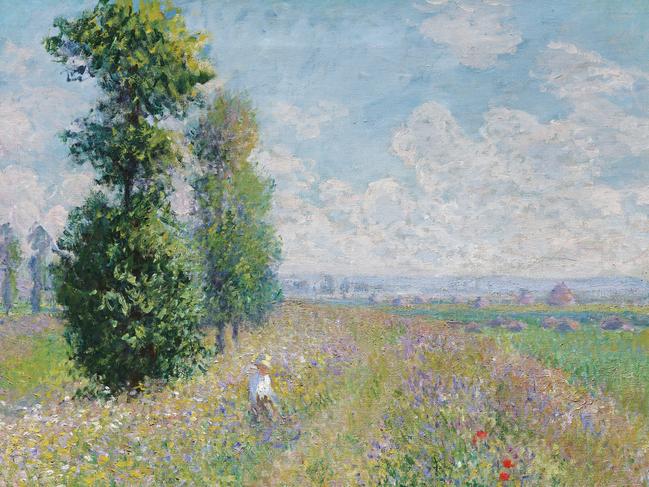

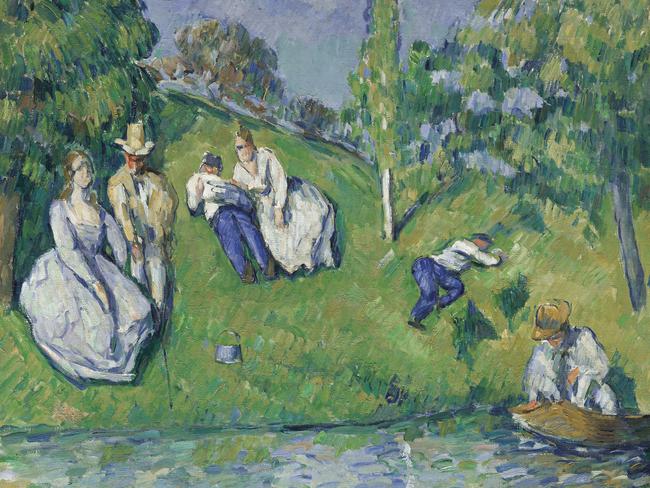

Paul Cezanne’s Fruit And A Jug On A Table, c. 1890-94, Edouard Manet’s Street Singer, c. 1862, and Claude Monet’s Poppy Field In A Hollow Near Giverny, 1885, are just a few of the works that will be new to audiences, unless they’ve been lucky enough to see them in Boston.

Another such work is Vincent van Gogh’s Houses At Auvers, 1890, one of 70 paintings the artist made in 70 days near the close of his life when he was driven by mania.

For NGV senior curator of international art Dr Ted Gott, “it’s pretty remarkable” to have so many works never before seen in Australia.

“This is an absolutely cracker show,” Dr Gott says.

“Every painting in it is better than the one you just saw. This is one of the best shows we’ve ever put on, and I’m not exaggerating.”

Unusually for an Impressionist exhibition, this show reveals the precursors and origins of French Impressionism, says NGV senior curator of international exhibition projects, Dr Miranda Wallace.

Many people are familiar with the names of leading Impressionists such as Renoir, Monet and Camille Pissarro, if only for the eye-watering prices they fetch at auction. And of course there are great examples of the works of these artists, and many other artists, in the show.

But have most people heard of Constant Troyon, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Paul Huet or Theodore Rousseau? Likely not. These artists prepared the soil for the subsequent flowering of Impressionism, and their paintings are generously represented in the show.

Taking advantage of the invention of paint in portable tubes, and new pigments, these artists broke with academic studio tradition and painted out of doors — what the French call en plein air. Their favourite painting destination was the Forest of Fontainebleau near Barbizon, resulting in them being dubbed the Barbizon School.

Eugene Boudin is hardly a household name in Australia, either. But without his salty harbour scenes and scudding skies, Monet would never have been Monet. The most famous of all French Impressionists said so himself. If Boudin hadn’t taught him to paint with his easel stuck in the beach at Le Havre, Monet’s mature art — all those poppy-studded fields and trailing water lilies — could never have existed. A large section is devoted to Boudin.

There are 10 themed sections in the exhibition, the most unexpected one dealing with works on paper.

It’s a medium not automatically associated with the French Impressionists, and it’s typical of these artists that they used printmaking in an experimental way, Dr Wallace says. There are 15 prints in the show.

The climax is a staggeringly beautiful, oval-shaped room inspired by the Musee de l’Orangerie in Paris, where Monet’s late water lilies have hung since the 1920s.

In the NGV, this final room, showcasing no fewer than 16 Monet paintings, is a celebration of shimmering light and dancing colour.

Scorned and mocked when they began to exhibit their work in the 1860s and 1870s, the Impressionists are today among the most recognisable artists in the world. If you had to resort to the language of capitalism, you could call them a brand.

It was the early, dismissive art critics that called their work “impressions” in a direct attack on what looked to them — and to many others — like crude, unfinished works that stood in aggressively dumbed-down opposition to the government-controlled Salon system.

The Salon mandated what type of art was successful and what wasn’t, in the days before private galleries and art dealers took up the new art and began to promote it.

In early-20th century Boston, a city of wealthy industrialists, there was plenty of money to buy art for the sprawling, palatial homes in fashionable neighbourhoods. A lot of that money ended up in Paris, in exchange for masterpieces of the famous art capital’s iconoclastic young painters.

Philanthropists such as John Taylor Spaulding, David P. Kimball, Miss Elizabeth Howes and Miss Amelia Peabody acquired sublime Impressionist paintings and eventually gifted them to their city’s Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Three years ago, MFA Boston and the NGV initiated discussions about collaborating on this exhibition. No one could predict that Covid-19 would frustrate and complicate the organisation of the show, nor that those hurdles would be overcome.

“The fact we were able to get four couriers (to accompany the works to Australia from MFA Boston) was a really important part of it,” MacBeth says. “With a show of this scale and quality we felt we needed to have at least some of the professional staff on the ground here to work with NGV staff. It was a game-changer.”

With Melbourne now in lockdown again, who knows whether French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston will open as scheduled on Friday and be able to welcome the expected crowds of local and interstate visitors expected to flock through its doors. The gallery would say only that it will follow state government health directives, as it did in shutting up shop on Friday.

Claude Monet lived through the 1918-1920 Spanish flu pandemic, not dying until 1926. It would be interesting to know what the Impressionist painter would say to us about Covid-19 in 2021.

Details: ngv.vic.gov.au