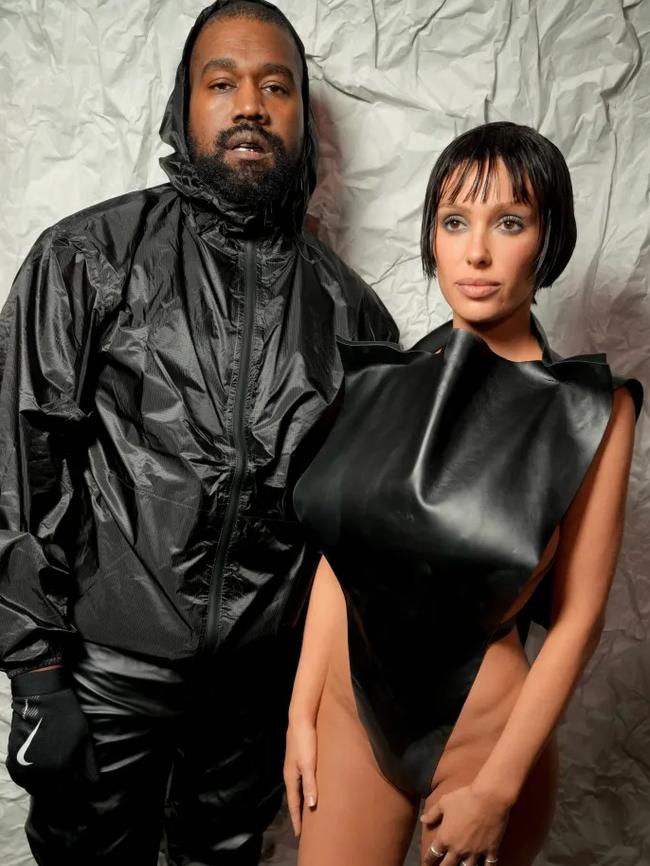

From Kanye to Gauguin: Can you loathe an artist but love their art?

Whenever an artist’s actions or beliefs contradict your own, a dilemma emerges: can you still consume their work? The answer isn’t black and white.

Entertainment

Don't miss out on the headlines from Entertainment. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The Harry Potter series is a cherished part of my childhood. But author J.K. Rowling’s problematic and very public views on the transgender community don’t sit well with me, and have caused me to reflect on my love of her work.

Can you loathe an artist and still love their art?

This is an increasingly common dilemma in the arts and culture space, amplified by social media discourse and movements like #MeToo.

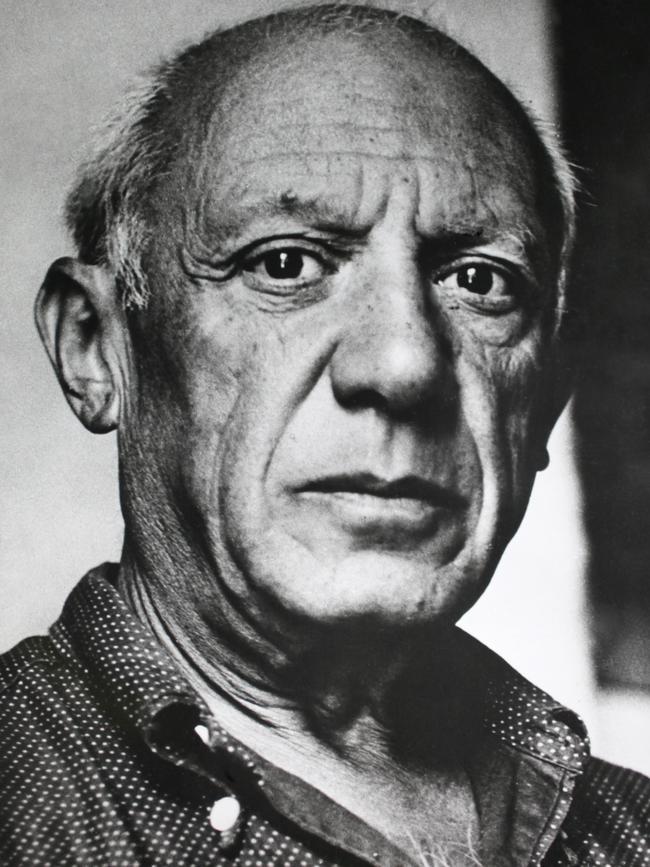

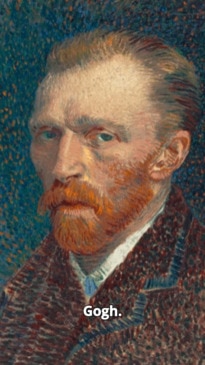

Male artists are typically at the centre of this debate – from master painters Pablo Picasso and Paul Gauguin, through to Michael Jackson, Bill Cosby, Kanye West, Kevin Spacey, Woody Allen, Harvey Weinstein – the list goes on.

But women aren’t immune, says Lauren Rosewarne, an associate professor in social and political sciences at the University of Melbourne.

Just look at Rowling, Ellen DeGeneres and more recently, Blake Lively, who has drawn criticism from domestic violence survivors for her tone-deaf promotion of her new film, It Ends With Us.

Rosewarne believes some artists’ contributions are significant enough that “you don’t write these people out of the history of culture production”, adding Picasso and Michael Jackson to this category.

But ultimately, whether you can hold disdain for an artist’s actions or beliefs, but love for their work, is “a very personal decision”.

“It is dependent on how much you invest in the biographies of your favourite artists (and) how much you care about the issue (related to their transgression),” she says.

“For example, if sexual misconduct is something that offends you greatly, then (when an artist is involved in) sexual indiscretions or sexual crimes, you might make a political decision to stop consuming that person’s art or material, because you are construing any support you give their cultural output as putting dollars in their pocket, or in their estate’s pocket.”

Others may choose to rationalise their continued consumption of works by a divisive artist, using arguments like “it was a different time”, or their creations are so profound because they’re a “tortured artist”.

Or, they may decide their emotional connection to their art is too strong to sever.

“You might have loved Michael Jackson’s music growing up, it might be of intrinsic value to your memories of your childhood or adolescence,” Rosewarne says.

“Therefore, being told you can’t listen to that music anymore, even just feeling like there’s something shameful about it, you may see that as personally insulting your memories.”

There is no right or wrong approach, she adds. And consumers have every right to change their minds.

“There’s probably no ethical consumption under capitalism,” she adds.

“But if you truly want escapism through art, if you just want to relax to music or a film, you’re probably better off not deep diving into the artist.

“If you’re someone who wants to be politically informed and make choices to only patronise artists that are in line with your values, you do have to do some research – keeping in mind, any story generally has more than one side to it.”

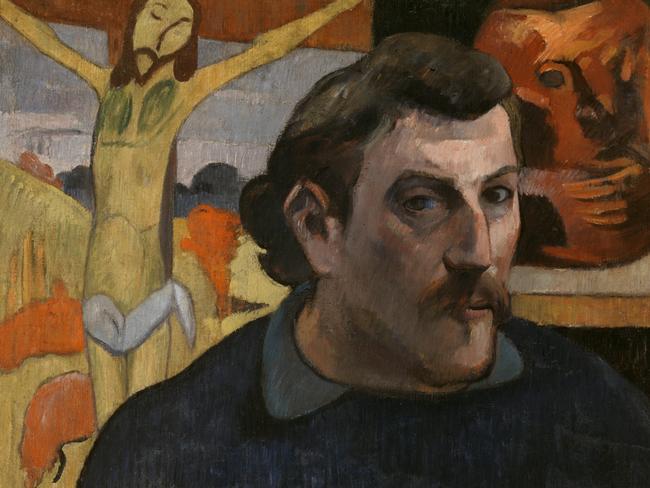

Samoan-Australian journalist Sosefina Fuamoli was confronted with this dilemma after agreeing to host a podcast to accompany a National Gallery of Australia exhibition showcasing Paul Gauguin in Canberra.

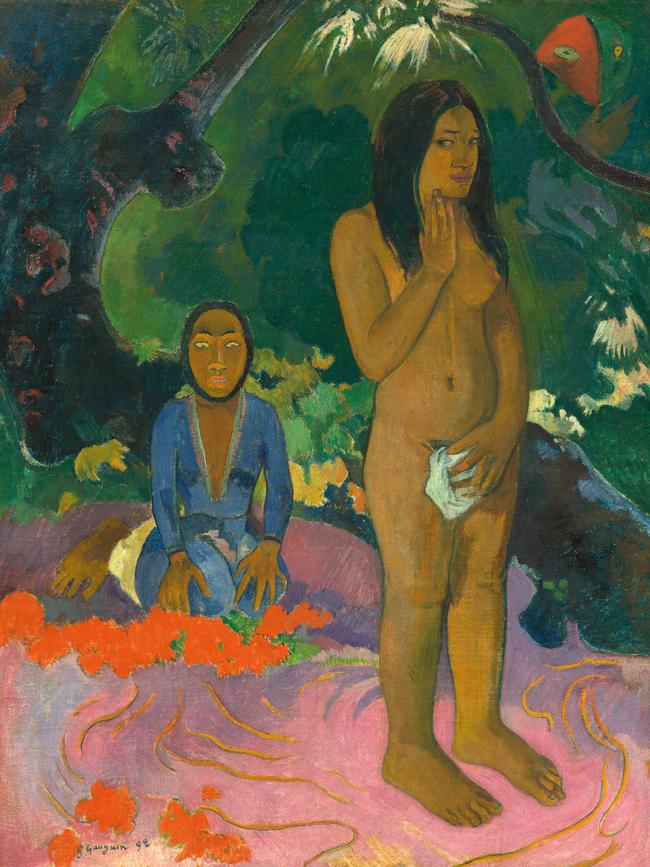

The French post-impressionist is simultaneously celebrated for his profound influence on 20th-century art, and maligned as a sexual predator and cultural appropriator.

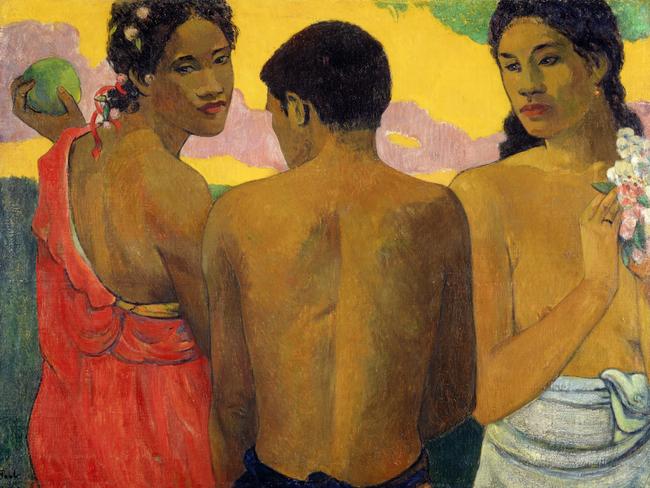

Both these views stem from his time living in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands, during which he created richly coloured paintings of the South Pacific people and landscapes.

Many of these are on display in the NGA exhibition, Gauguin’s World: Tona Iho, Tona Ao – the biggest showcase of the artist’s work ever seen in Australia, with more than 130 pieces from 65 international lenders curated by former Musée du Louvre director Henri Loyrette.

The second part of this title translates loosely to “his true world, his true self”, so the NGA wanted to examine this concept from Pacific Islander perspectives. Enter Fuamoli.

The award-winning journalist’s position on the divisive French artist is clear.

“I don’t love old mate Gauguin,” she says on the first episode of the podcast, The Gauguin Dilemma, which she created in conjunction with the NGA.

“Not many Islanders do.

“But I also don’t think cancel culture has been very effective. So I went online to see what people are saying about him. And the question everyone is asking is, ‘Can you loathe an artist and still love their art?’

“This dilemma actually felt exciting to me.”

NGA senior curator of international art Lucina Ward doesn’t hesitate when this question is posed to her.

“Most definitely,” she responds.

“If there was no Gauguin, 20th-century artists and art would be really radically different,” she says, highlighting the Frenchman’s revolutionary use of “colour, a simplicity of forms and a kind of rawness”.

Picasso and Henri Matisse, in particular, took inspiration from Gauguin, Ward adds: “Matisse is very conscious that he’s travelling in Gauguin’s footsteps with the bright use of colour.”

She understands art consumers are likely to be fascinated by artists’ biographies, but urges them not to “rely on an artist’s biography to interpret a piece of art”.

“There are a number of ways to look at art (including) what effect does the work of art have on us?” Ward says.

“I also think it’s very important to be aware of the broader political, societal and cultural effects (on art and artists). Gauguin doesn’t become the sort of person that he is without the effect of society and culture around him.”

Gauguin’s biography isn’t easy reading. As Fuamoli puts it: “(He was) a white European man, coming to the islands with this perception (that he could) escape the constraints of Europe and France, wanting to live a ‘native’ life.

“In some ways, for him, this meant … revelling in the exoticism and the fetishisation of women in French Polynesia, taking child brides.”

Not only did Gauguin make these transgressions, he chronicled them on canvases.

“This isn’t like Woody Allen or Harvey Weinstein, whose encounters with women and girls were off screen,” Fuamoli explains on the podcast.

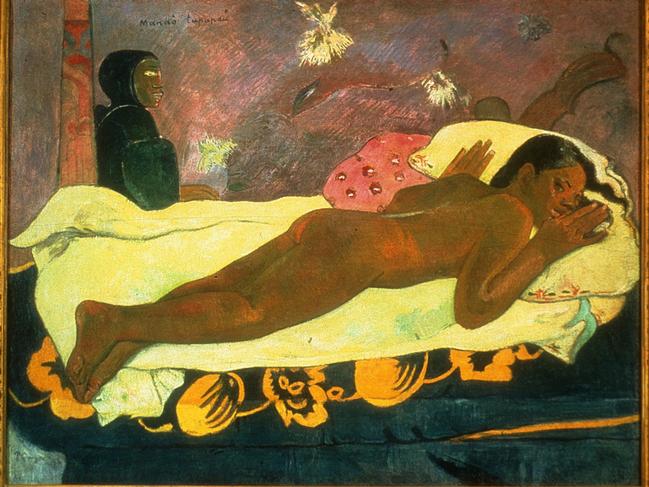

She raises the example of his 1892 painting Manao Tupapau, or Spirit of the Dead Watching. It depicts Teha’amana – a 13-year-old girl Gauguin took as a wife, after moving to Tahiti, away from his Danish wife, Mette, and their children – lying naked and afraid on a bed.

“Gauguin said he was trying to represent the Polynesian fear of the Tupapau or ‘spirit of the dead’, which is represented here as an older woman in a black cloak in the background,” Fuamoli says.

“But Teha’amana is not looking at the spirit. Her eye line is looking toward where Gauguin would have been standing to paint her.”

Separating the art from the artist is clearly not an option in Gauguin’s case. But Fuamoli would hate to see his art eradicated from public view.

“That would be taking away our agency as Pacific Islanders, and particularly Islander women, to have those hard conversations about who he was as a person and an artist,” she says.

“Being able to talk about him, about why his art, his life, his legacy are so problematic in itself is an act of decolonisation.

“I don’t necessarily believe in absolute cancel culture. I just don’t think it exists. But I do believe in the necessity of critical thought and critical conversation, because otherwise, how are we supposed to move forward?”

Ward says “cancel culture is a one-way street”, and the NGA preferred to spark a dialogue by engaging contemporary Pacific artists and scholars in the Gauguin’s World exhibition. Examples include Fuamoli’s podcast and a parallel exhibition of contemporary works from the SaVAge K’lub collective titled Te Paepae Aora’i – Where the Gods Cannot be Fooled. Polynesian scholars also contributed essays to the exhibition catalogue.

“We made the decision very early in the planning to acknowledge that, of course, Gauguin has a very complex legacy,” Ward says.

“We can’t change history, it would be foolish to avoid Gauguin’s work in art history. But maybe we can influence the present and hopefully even the future.

“If we shut down all discussions of these complex issues – issues of colonialism, Gauguin’s sexual relationships with very young women, his unpleasant biography, his relationship with (his wife) Mette, I think we’re at risk of potentially repeating various issues.

“It’s much more constructive to try and discuss these issues.”

Gauguin’s World: Tōna Iho, Tōna Ao is at the National Gallery of Australia until October 7. Listen to The Gauguin Dilemma at nga.gov.au/podcasts/the-gauguin-dilemma or via your podcast app of choice

Last chance to enter Gauguin’s World

Australian audiences have just two more weeks to experience Gauguin’s World, the largest display of works by the influential French artist this country will ever see.

Visitors will view more than 130 works by Paul Gauguin – loaned to Canberra’s National Gallery of Australia from art institutions and private owners around the world – including his richly coloured portrayals of the Pacific Islands.

They will also be exposed to the seedier parts of Gauguin’s legacy: his enduring reputation as a sexual predator and colonial opportunist.

NGA senior curator of international art Lucina Ward warned that after Gauguin’s World: Tona Iho, Tona Ao closed on October 7, “you’re not going to see a Gauguin exhibition like this again in Australia (or) “anywhere else in the world”.

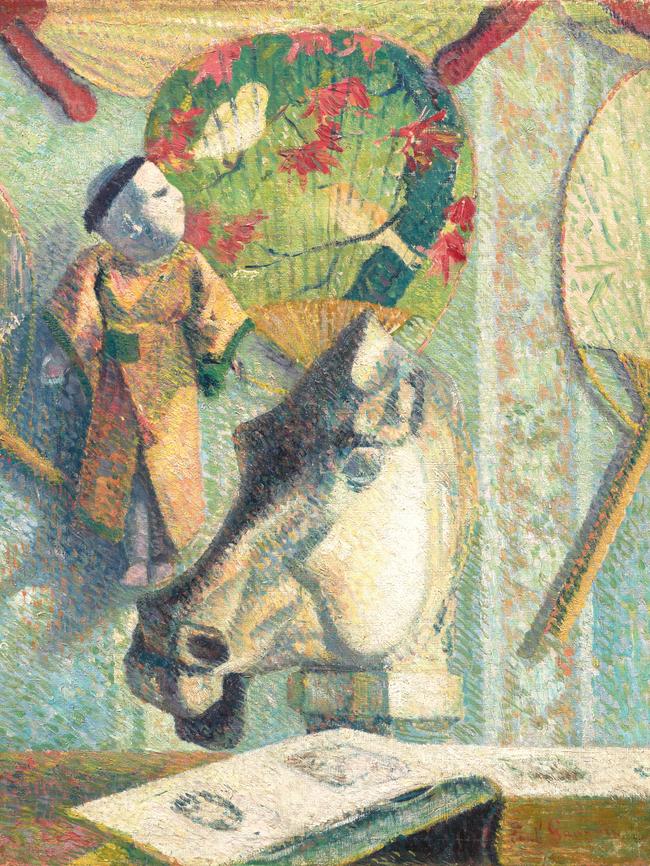

Ms Ward said while the post-impressionist was best known for his portrayals of Pasifika women and tropical landscapes, exhibition visitors had been drawn to Japanese art-influenced work Still Life with Horse’s Head.

The Blue Roof or Farm at Le Pouldu – a painting worth $9.8m, which the NGA has permanently acquired – had also been popular.

“People have an image of Gauguin in their minds, they feel like they know the work. But they’re less conscious of the development of the artist,” she said.

“(Visitors are saying) to me are, ‘I knew Gauguin was a painter, but I had no idea he made ceramics, sculptures and prints’.

“(In Gauguin’s World) you also see how closely he draws on the previous generation of artists. There’s a painting of Paris in the first room you’d be very confident was a Monet.”

More Coverage

Originally published as From Kanye to Gauguin: Can you loathe an artist but love their art?