Dr Terry Goldsworthy outlines what state government should be doing about youth crime crisis

Queensland’s youth crime crisis is at boiling point, but state government measures are just ‘smoke and mirrors’. Here’s what they should be doing, writes expert Terry Goldsworthy.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Queensland’s youth crime crisis is at boiling point.

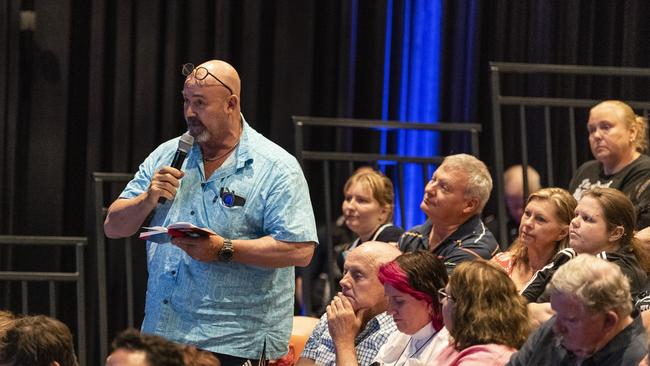

Just last week a community crime forum was called in Toowoomba following the death of a 75-year-old man who was allegedly attacked by a number of youths. At the forum, Queensland Police Commissioner Katarina Carroll, described the current crisis; “We have seen in the last 12 months an escalation of offending that we haven’t seen before”.

Examination of police crime data shows the overall crime rate in Queensland has risen seven per cent in 2021-22, the rate of break and enters has risen 18 per cent, stolen vehicles 13 per cent, assaults went up 60 per cent. The number of robberies is up 29 per cent.

In 2020-21 Queensland accounted for 27 per cent of all stolen cars in Australia. In Queensland, police are hamstrung by a restrictive pursuit policy.

The perception is that stealing a car in Queensland is a low-risk criminal enterprise. Only a week ago we saw youth offenders flee an alleged home invasion and brazenly drive a stolen vehicle from Brisbane until they crossed the border into New South Wales, where the police promptly intercepted and arrested them.

We now know that serious repeat youth offenders account for 17 per cent of youth offenders, up from 10 per cent in 2020, and commit 48 per cent of youth crime.

Despite only accounting for 16 per cent of all offenders, youth make up 54 per cent of robbery offenders, 53 per cent of stolen vehicle and 50 per cent of break and enter offenders.

So how did we get here? In 2016 the Labor government removed the offence of breach of bail for youth offenders, it also outlined that for youth offenders a detention order should be imposed only as a last resort and for the shortest appropriate period.

In 2019 the current government further weakened youth justice laws by passing legislation that was designed to facilitate more grants of bail to youth offenders.

The new laws, formed part of the Queensland Government’s $550 million investment in youth justice reforms, including new programs and services to keep young people out of custody and from re-offending, it sounded admirable at the time.

‘TOOK A YEAR FOR GOVT TO REALISE MISTAKE’

It only took a year for the government to realise its mistake and enact more amendments to try and fix the problem in 2020. Yet still, the bar was set too low in terms of allowing the hard-core offender back out onto the streets to continually reoffend.

There have now been two sets of additional Youth justice reforms since to try and combat the crisis, both are best described as inept and ineffective.

Despite the shrill calls of panic from the progressive elements in our society, few youth offenders get sent to jail. The Children’s court Annual report released last month showed that in 2021–22 a detention penalty was only imposed in 6.6% of convicted youth appearances.

Raising maximum sentences for stealing a vehicle, as the government has in its latest youth justice reforms, is simply smoke and mirrors if no-one gets the maximum.

Data from the Queensland Sentencing Advisory council showed that the average period of detention for youth offenders convicted of stealing a vehicle was 3.6 months, only 6 per cent of youth offenders who stole a vehicle went to detention.

The Atkinson review of the governments youth justice reforms released in 2022 showed that offending by young people on bail had increased.

MORE THAN HALF OFFENDED ON BAIL

Some 53 per cent of young people on bail reoffended whilst on bail, 19 per cent committed serious offending and seven per cent committed an offence leading to death or serious injury whilst on bail.

These figures are simply unacceptable. The offence of breach of bail for youth offenders needs to be introduced immediately to give an effective an efficient option for police to take action for youth committing offences on bail. (Overnight, the Palaszczuk government backflipped and announced it would reintroduce breach of bail as an offence after repeatedly saying it would not be effective)

Backgrounding this are moves to decriminalise youth offenders aged 10-12 years, the Queensland government has supported this proposal, as part of a broader push to raise the age of criminal responsibility to 14 years. As the Police Union noted, it will create a generation of invisible offenders.

An example of the failures of the youth justice reforms put in place by the government are the electronic tracking devices.

At the forum in Toowoomba the police minister claimed that the trial of the trackers “was very successful”.

SHORT TERM OFFENDING SOLUTION SIMPLE

The Atkinson review showed that instead of the 100 expected to be issued, only three had been, at a cost of some 11.5 million dollars. If that is a success, I would hate to see a failure.

The short-term offending cycle of serious repeat offenders needs to be stopped. If you commit a serious offence on bail there should be no show cause situation, it should be the case that you remain in custody until your matter is finalised.

The government can easily pass legislation to this effect. Therapeutic interventions to address the multifactorial causes of serious youth offending can come later to stop the long-term offending cycle.

The community is right to be angry, the government must listen to the people and take appropriate action to address this crisis. Community safety must come first.

* Dr Terry Goldsworthy is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice and Crimonolgy at Bond University, Gold Coast

Originally published as Dr Terry Goldsworthy outlines what state government should be doing about youth crime crisis