Stalking Our Streets documentary: Inside the mind of teen offenders

Often fuelled by ice, a group of troubled teens hits the street every night to perform a “creep” until the sun comes up. Watch this chilling documentary, which takes you into the mind of these young offenders.

Toowoomba

Don't miss out on the headlines from Toowoomba. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In one of many cities in Queensland, a group of troubled teenagers are preparing for their nightly search.

These children, often as young as 14, hit the streets in the late hours after a day of heavy drug use.

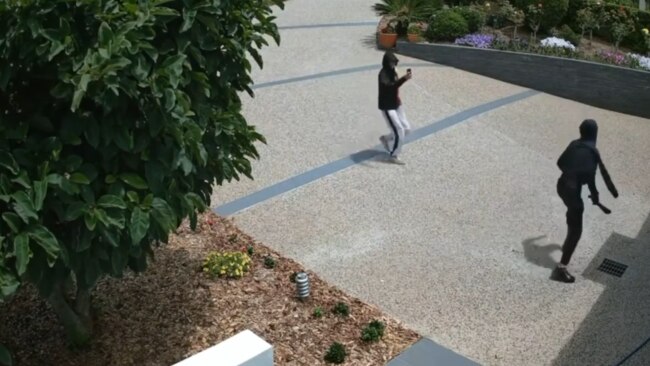

They will select a suburb to perform what is known as a ‘creep’ – stalking a series of unlocked homes to break into or vehicles to steal.

Sometimes they walk away empty-handed, but most nights end with a joyride in a stolen car.

Other nights end with a stolen licence, which they sell on to future fraudsters.

Often fuelled by amphetamines, this group of young people may continue their creep until the sun rises.

The following day, the cycle will repeat.

This is where the teens find their comfort zone.

It’s where they fit in.

And, they feel, it’s the one thing they are good at.

A former offender has lifted the lid on what a day in the life for these teens looks like, and why they continue their cycle of offending.

The Covid phenomenon

As the state dealt with the aftermath of the global pandemic, Queensland Police have admitted a severe increase in youth offending which they are still trying to understand.

Police Commissioner Katarina Carroll said a small cohort of young people were committing more offences as the state emerged from two years of lockdowns and restrictions.

“I went to a forum very recently where an academic spoke about this, and candidly said where you would find yourself in 10 years’ time, Covid has almost compressed that,” she said.

“It is a different world coming out from Covid, and we as a policing department have clearly seen that.”

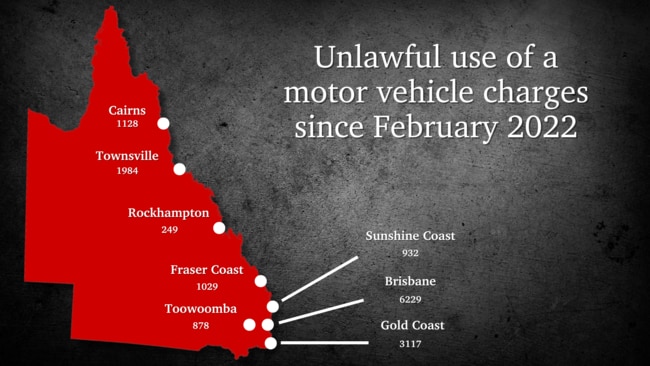

Numbers obtained from the Queensland Police Service tell a similar story.

The number of stolen car offences has spiked by nearly 50 per cent in the past 10 years.

Since February 2022 unlawful use of a motor vehicle charges have surged all across the state.

Inside the creep

David’s* connection to young offenders began with selling ice on the streets of a Queensland city.

“I would buy bigger quantities of ice and sell it – they would know me through friends of friends,” he said.

It was on these streets he saw teenagers – some as young as 14 – develop a disturbing habit that started during the day and often continued until the sun rose.

“During the day they would laze around, smoke pot all day and kick back,” he said.

“When it got late they’d go out at night, do what’s called a creep or a search.”

A creep is what offenders call their nightly routine – stalking suburbs around towns at night, searching for unlocked homes and vehicles.

The aim is usually to obtain a vehicle, sometimes used to commit more serious offending like ram raids.

Other times they sell the vehicles onto other offenders for cash, which they then use to purchase more drugs.

Their search targets also included wallets, jewellery and anything else they deemed high value.

“The crowd they were growing up in, they were heavily into crime. It’s what they were brought up with,” he said.

“No matter what night it was, it would get to 10, 11 o’clock and just look at each other and say ‘Are we going out? We going out?’”

Almost every creep ended with stolen goods.

“They’d get a car most nights if they persisted long enough,” he said.

“There’d be hard nights where they’ve been dropped in a suburb far away. They’re out all night and they have to get the bus home in the morning.

“But if they were doing houses, every night. They would come away pretty cashed sometimes.”

Undeterred by the threat of juvenile detention, the teens continued their cycle almost every night driven on adrenaline.

“A thrill and because it was their comfort zone. It was what they were used to. They fit in that space. it’s what they’ve been doing for a long time and they were good at it,” David said.

“That’s what they’d been doing for a long time, and they were good at it. So they felt like a bit of a community of the people who did it.

“I think they know until they turn 18 when they face real punishment they’re going to get away pretty light handed.”

David said a difficult home life often kept many on the streets, who would meet up after a stint in detention to continue their cycle of creeping.

“They were coming from torn backgrounds, parents that use drugs. They didn’t have much hope to get a normal job, they were just in a life of crime,” he said.

“They’re young kids with heaps of potential. they get thrills from the wrong things, their doing drugs.”

For police and the courts, it’s difficult to strike a balance when it comes to sentencing young offenders.

“In some instances, the only way you can get respite in the community is if they are in detention centres,” Ms Carroll said

“But we also know having kids in detention centres for a long period of time doesn’t work.

“It is a really complex issue.”

Back on the right track

Jen Shaw is one person who has seen first-hand the potential of many young offenders, through her social enterprise Emerge.

Ms Shaw has previously worked with kids between the ages of 11 and 19 who are often engaged with drug use and criminal activity.

“We work with them until they get back on their feet and figure out who they want to be,” she said.

“It’s always started with employment and crisis outreach, and as we’ve moved on over the years it’s turned into the things they’ve needed.”

That has included finding accommodation for young people, and activities that give them routine and structure with a sense of belonging.

Ms Shaw said ice was a massive factor plaguing some young people, which she described as “off the rails”.

“You have the most amazing kids, they start using substances and they aren’t themselves,” she said.

“They’re looking for the medicine, something to make them feel better.”

Despite the issues many of these young people face, Ms Shaw said she had “never met a bad kid”.

“We meet these amazing kids, they’re smart, there’s lots of good code in them,” she said.

“They’re just kids. We always have a saying – you love the kid, you hate the behaviour.

“You’ve got to get the source of what it is that is making the kid act like that.

“If you don’t have good people in your life at home … who’s going to teach you right from wrong and what’s normal?”

Unfolding tragedies

But a number of recent tragedies have allegedly involved youths.

Two youths have been charged after Emma Lovell, 41, was allegedly stabbed in the chest while fighting off intruders in her home

Robert Brown died after he was allegedly robbed in a sickening and attacked outside a Queensland shopping centre

A 17-year old hit and killed Matthew Field and a pregnant Kate Leadbetter in a stolen car as they were walking in Brisbane.

Kelsie Davies, Sheree Robertson and Michale Chandler were killed after a horrific crash allegedly caused by a 13-year-old in a stolen car.

In total, 18 people have died in the past two years in this youth crime wave.

Seeking answers

Commissioner Carroll admits this cycle of offending is one of the most complex issues young people face.

“It is incredibly sad in many ways,” she said.

“Why I say sad is because I know some of these children we deal with come from really complex, very dysfunctional and difficult backgrounds.

“But it’s unacceptable as well. You’re assaulting people, you’re hurting other people. You still need to be held accountable for your behaviour.”

She said the key to alleviating the situation was not just responding to the crimes, but intervening and disrupting their behaviour before the offending starts.

David said many young people he associated with were “thinking pretty narrow”.

“I’d tell them there’s a lot more to life than what they’re doing,” he said.

“They think that’s the only thing they can do because they’re good at it.

“There’s heaps they can do, they’re just not trying to expand their horizons.”

Ms Shaw said there was no easy solution, and it would not come quickly.

“There’s absolutely nothing we can do straight away that’s going to fix it,” she said.

“We just take a breath, look at who is doing what well and get back on with the job of looking after kids.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Stalking Our Streets documentary: Inside the mind of teen offenders