Explained: What happened to El Niño and Queensland’s dry summer outlook

Record-high sea temperatures and the biggest volcanic eruption in 140 years could be behind El Niño’s failure to deliver what was predicted to be a dry Queensland summer.

QLD weather news

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD weather news. Followed categories will be added to My News.

As an intense storm season unfolds with flash flooding and more rainfall forecast, many Queenslanders are asking the question – what happened to El Niño?

The Bureau of Meteorology declared an El Niño weather event in September – a climate driver that generally leads to drier and hotter than average weather based on the strength and direction of trade winds, Pacific Ocean temperatures and rainfall movements.

While an El Niño is typically associated with hot, dry weather, it does not automatically cancel out storms or rainfall events, especially during storm season which in Queensland occurs between October and April.

While dry conditions were experienced in October and November, December was rife with intense rainfall, severe storms and an early cyclone, which could be partially due to a volcano eruption in Tonga two years ago.

Queensland’s rainfall average during December was 22 per cent above the mean range, with parts of the state recording on average 100mm – the highest in the country.

What happened to El Niño?

Record-high global sea surface temperatures and conditions more aligned with a La Niña event were driving Queensland’s significant storm season, according to the Bureau of Meteorology.

It said in a statement that a positive Southern Annular Mode (SAM) – north-south movement of strong westerly winds – was persisting, which was “unusual” during an El Niño event.

A positive SAM historically increases the chance of above average rainfall as it shifts westerly winds south over southeastern parts of the country, including South East Queensland.

Global sea surface temperatures were also the highest on record between April and November 2023, which also fuel increased rainfall and tropical storms.

What is the outlook for the rest of summer?

With SAM still positive, above average rainfall is likely to continue across southern parts of Queensland into January.

“The presence of a positive SAM, combined with very high temperatures in the Tasman Sea likely contributed to rainfall events in eastern Australia in December and January,” the Bureau statement said.

“The widespread and regular rainfall across southeastern Australia across multiple months is similarly unusual for El Niño.

“The January to March long-range forecast … indicates an increased chance of above median rainfall for parts of South East Queensland, eastern NSW and Victoria, and more neutral rainfall chances over the interior and southern parts of the country.

“Chances favour drier than average conditions for most of WA, parts of the NT and some northern parts of Queensland.”

Did a volcano eruption kill El Niño?

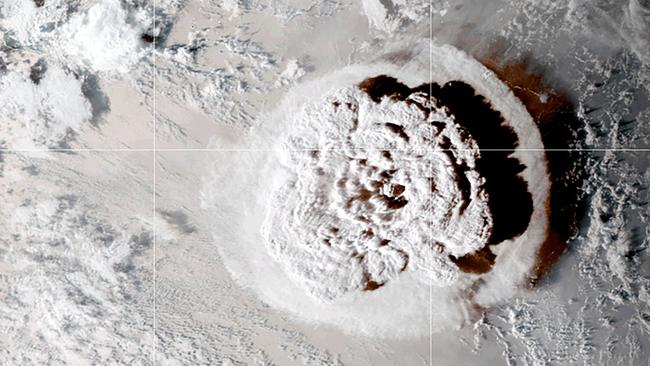

A Tongan volcanic eruption almost two years ago could be cancelling out El Niño and the impacts it has on Queensland’s climate.

Sky News meteorologist Rob Sharpe says when Hunga Tonga – Hunga Haʻapai Volcano erupted in January 2022, 146 gigalitres of water – equivalent to 60,000 Olympic sized swimming pools – was launched 40km above the earth into the stratosphere,

It was the biggest volcanic eruption in 140 years.

The water remains in the stratosphere – and could so for the next decade – and has spread right around the world, staying 10km above the ground.

While the water itself won’t cause rain (it doesn’t rain out from the stratosphere), Mr Sharpe said it was delaying the shrinking of the hole in the earth’s ozone layer.

Typically, by the start of December the ozone hole is closing for the summer. But it’s still the size of Antarctica – a new record for this time of year.

Mr Sharpe said a larger ozone hole led to a stronger polar vortex near the antarctic, or stronger winds contracting close to Antarctica.

That produce a positive SAM, which then typically produces more cloud and rainfall, particularly over eastern Australia.

“In situations like this, SAM can become fairly dominant for a few months – hence its likely impact on Australia’s summer,” Mr Sharpe said.

Could El Niño be cancelled?

As part of its El Niño forecast, the Bureau predicted typical summer severe storm activity and risk of flooding, as well as fewer tropical cyclones.

But it said “no two El Niño and IOD events are the same and their impact on Australia varies.”

“This is particularly true of summer months. Once the northern monsoon arrives, the influence of both El Niño and a positive IOD is diminished, and the chance of summer rainfall events increases,” the statement said.

Around half of the past El Niño events have included heavy rainfall events, particularly across parts of eastern Australia, including December 2009 and August 2015.

Asked whether it was possible an El Niño declaration could be cancelled, the Bureau said it would “continue to update the community as new observations of the ocean, land surface and atmosphere are incorporated into our forecast systems”.

Why El Niño is here to stay

Prior to the El Niño declaration, the Indian Ocean Dipole strengthened rapidly, leading to record-breaking dry weather conditions in August, September and October.

“August to October was the driest such period on record for Australia, with very warm temperatures,” the statement said.

“September 2023 was the driest September on record and the second driest month ever on record.”

Latest climate driver forecasting shows a strong El Niño outlook, with the event to persist through to March, with warm daytime and night time temperatures at least twice as likely for the next month.

The Bureau said its long-range forecast for summer indicated increased likelihood of above average rainfall during January, but below average rainfall for the tropics.

It says this is typical of an El Niño year as a positive Indian Ocean Dipole – a climate pattern affecting the Indian Ocean that usually leads to less moisture and therefore rainfall – tends to be weakened over summer months.

While January to March will see higher than average rainfall, long-range forecasting shows temperatures will also be more than twice as likely to be higher than usual.

This is due to the active El Niño, and the easing of the positive IOD combined with the persistently warm oceans.

Queensland’s wild storm season

December 4: Severe thunderstorms moved across the Sunshine Coast bringing giant hail, gusty winds and heavy rainfall. Gympie and Maryborough, in the southeast of the state, reported hail with some hailstones around 10cm in diameter (hailstones with diameter greater than 5cm are classified as giant hail) and wind gusts in Maryborough exceeded 85km/h resulting in fallen trees.

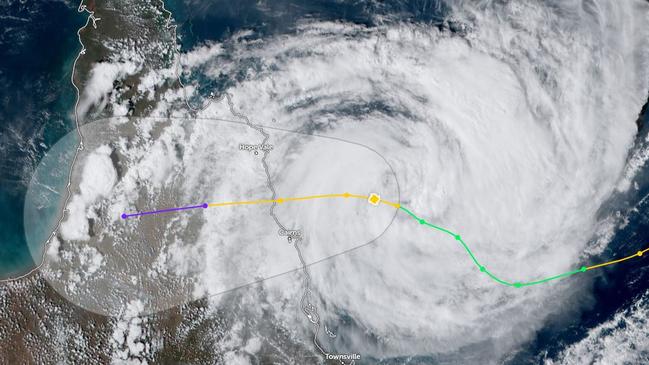

December 5: Tropical Cyclone Jasper formed on December 5 from a tropical low near the Solomon Islands. It quickly intensified and reached a Severe Tropical Cyclone strength (Category 3) on December 6 while moving south-westwards towards the Coral Sea. Tropical Cyclone Jasper intensified further reaching its peak intensity (Category 4) on December 8, but subsequently weakened to Category 2.

December 13: Tropical Cyclone Jasper’s outer rainbands started affecting Queensland’s North Topical Coast on December 12, and its core crossed the coast around 9pm on the 13th in the vicinity of Cape Tribulation (near the indigenous community Wujal Wujal), south of Cooktown. After landfall, it was downgraded to a tropical low. Ex-Tropical Cyclone Jasper brought to Northern Queensland damaging winds, intense rainfall, flooding and storm surge. Over 40,000 people were without power and there were many reports of downed trees, from Port Douglas to Daintree Village. Persistent rainfall continued as ex-Tropical Cyclone Jasper very slowly moved across Northern Queensland over the several days. Due to its slow movement, high daily rainfall totals were recorded across a wide area between Cooktown and Cardwell. A number of stations in the region had their highest daily precipitation on record for December. This heavy rainfall resulted in flash flooding, landslides, road closures and riverine flooding across Daintree, Mossman, Barron, Murray, Mulgrave and Herbert Rivers.

December 15: A cluster of severe thunderstorms brought destructive wind gusts and intense rainfall to southeastern Queensland including Brisbane, and northeastern New South Wales. Daily rainfall totals to 9am on December 16 exceeded 100mm in parts of the Brisbane and Sunshine Coast area, with most of the rain falling in a short period of time. A wind gust of 169km/h was recorded at the Archerfield Airport (Queensland), an annual highest daily wind gust for this station which has 35 years of data. Extensive damage was reported, with numerous fallen trees that damaged powerlines leaving 35,000 customers without power.

December 18: On December 18, Daintree River at Daintree Village reached 14.85m, well above the major flood level of 9m, and above the old flood record of 12.6m from 2019. At Cairns Airport, the Barron River was estimated (the gauge was not available) at 4.4m, exceeding the 1977 flood level of 3.8m. Multiple sites in Northern Queensland observed 5-day rainfall accumulations (14 to 18 December) in excess of 1000mm. The highest 5-day total (at the Bureau’s station) of 1933.8mm was recorded at Whyanbeel Valley station. The highest daily rainfall total during this event of 714.0mm was recorded at Mossman South Alchera Drive in the 24 hours to 9am on the 18th (Australia’s highest December rainfall total). Several non-Bureau sites recorded 5-day rainfall totals of more than 2000mm. By the 19th, the system weakened and shifted northward, with heavy rainfall easing.

December 19-26: A low pressure trough over western Queensland and New South Wales brought daily thunderstorms to eastern and southeastern Australia. Severe thunderstorms brought giant hail, well in excess of 5cm, to Gatton (Queensland) on December 23 and Burpengary on December 24. Severe thunderstorms brought more hail on December 25 to some areas in New South Wales and southeastern Queensland. In Orange (New South Wales), large hail was so extensive that it made the ground look like it was covered with snow, while in southeastern Queensland 130,000 customers were left without power due to strong winds. The strongest wind gust at a Bureau station was 106km/h at the Gold Coast Seaway, although thunderstorms may have caused even stronger localised areas of damaging or destructive winds. A tornado moved across parts of the Gold Coast and Scenic Rim on Christmas night, leaving destruction in its path. The outbreak of thunderstorms continued on the 26th, with thunderstorms across central and eastern Victoria, eastern New South Wales and eastern Queensland.

December 28-31: More settled weather returned to eastern Australia from December 28, but thunderstorms affected parts of New South Wales and Queensland on the last two days of the month. On December 30, thunderstorms developed in areas north of Brisbane, with reports of flash flooding, large hail and damaging winds. The highest daily rainfall total recorded to 9am on December 31 was 127.6mm at Beerburrum, Queensland.