Forensic anthropologist Donna MacGregor: The woman who reads skeletons

WHEN a charred, headless torso was found in southeast Queensland in 2013, there were no clues about who the person was. So police turned to the “bones lady” in the hope she could help. She did.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT all comes down to your bones in the end. They are all that is left when everything else has decayed and fallen away. They are your story.

Bones are the business of forensic anthropologist Donna MacGregor. She reads skeletons. She can tell how you lived, and in some cases how you died. She can see if you had a healed fracture, or carried a disease, were left or right-handed, your unique characteristics. Even tiny bone fragments will tell her how old you were, how tall, your gender, or what your ancestral background was.

“Dead men do tell tales,” she says, “and it is all in your bones.”

But you probably wouldn’t come to MacGregor’s attention unless something quite bad had happened to you. Her customers are not the people who have died peacefully surrounded by loved ones. If MacGregor is looking at your bones, there is more than an outside chance that you have become part of a crime scene, that the circumstances of your demise are suspicious, your death traumatic. Or that your remains have been found somewhere and you need to be identified. That can’t be good either. She deals with the decomposed, burned, dismembered.

MacGregor can narrow bone remains down to one or two people on the missing persons register.

“The human body is a big jigsaw,” she says. “You would look for defence wounds or nicks to the ribs or the hands. If a knife goes through, there will be markings on the bone. If we see a skull that has got an entry wound or gunshot exit wound, or there has been blunt force trauma or a fracture of the tibia, we will make comments.”

MacGregor, 44, is sitting in a meeting room at the Gardens Point Campus of the Queensland University of Technology, in Brisbane, where she is lecturer in anatomy at the School of Biomedical Sciences. She teaches undergraduate human anatomy and forensic anthropology.

“We are developing a virtual skeletal database of CT scans and using this to address knowledge gaps I have identified in years of doing this type of work. We are slowly developing new standards we can use in casework. My main interest is stature and age estimation techniques. And also factors that influence decomposition of the body.”

She is also the only forensic anthropologist in the army, where she is a Reservist posted to the Unrecovered War Casualties Unit.

“I sit in Medical Corps as a Special Services Officer. I had to go to Duntroon (Royal Military College, in Canberra) to do officer training. When I went to my recruit-ment (interview) they said ‘oh, you’re the bones lady’.”

From her window, high above the river, the city of Brisbane sprawls out and she knows that under the tin roofs, in the neat gardens and the office blocks, daily dramas are being played out that could have fatal endings. She knows what people are capable of. Dealing with death on a daily basis makes her watchful.

“You are vigilant of not making yourself a target, having an instinct for when something is not right and getting out of there. But I embrace life and enjoy it,” she says.

MacGregor is on call to the Queensland Police when skeletal remains are found. She is who they phone when someone has gone to considerable lengths to make sure a body can’t be recognised.

When a charred, headless torso was found near Gympie in September 2013, there were no clues about who the person was. The hands had been hacked off at the wrists to make sure there were no fingerprints. It was MacGregor’s job to build a biological profile.

“There was a lot of work Donna did that (helped) us,” says Brisbane Homicide Acting Superintendent Damien Hansen.

“She gave us a very small age range and said (the dead male) had possibly done manual labour because of some sort of decomposing of the spinal cord. She was spot on.”

When a man’s skull was found seven months later and 20km away, it was reasonable to assume that it had once belonged to the torso. “Anyone would have bet the house that they were connected,” Hansen says.

“We gave a profile and confirmed that it wasn’t related to the torso,” MacGregor says. “And then DNA confirmed they were separate.”

The skull belonged to Shaun Barker, 33, who had been abducted from a Gold Coast service station and suffered days of torture before being dumped in Toolara State Forest where his remains were set alight. Police believe it was a drug dispute.

(In March 2017 a jury found fisherman William Francis Dean guilty of murder and two of his co-accused, Stephen John Armitage and Matthew Leslie Armitage, were found guilty of torture and interfering with a corpse.)

It would take much longer to identify the headless torso.

“It was a frustrating job,” Hansen says. “Normally we can start off with a name and do victimology to give us a picture of the victim and associates. But we had nowhere to start for 10 months.”

Toxicology had found two drugs in his tissue.

“There was irbesartan, which is the most highly used blood pressure tablet in the country. And the other one was quinine, which may or may not need a prescription, that is a malaria muscle-relaxant thing. We went with the irbesartan and got a ridiculous number of hits nationally. We used Donna’s age group (estimation), which trimmed it down significantly and made it a manageable list.”

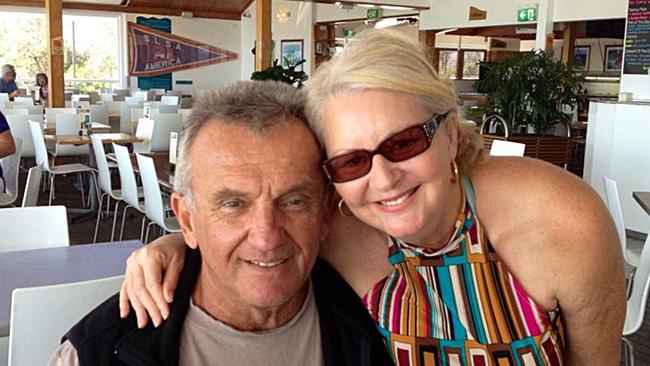

It was good old-fashioned door knocking, based on pharmacy records, and interviewing hundreds of people on the same medication that led police to the Tanawha home of George Gerbic, 66, formerly a prominent figure in the real estate industry and president of the local football team.

In June 2016, his fiancee, Lindy Yvonne Williams, then 58, was committed to stand trial for allegedly hacking him to death and interfering with his corpse. She denies the allegations and is yet to face trial.

“You have no idea how idea how much work the detectives and forensic people did,” MacGregor says. “The investigators went through immigration records, cell towers, Medicare records, you name it. It can’t be done by any one person, it includes the pathologists, detectives and the anthros and the crime scene people.”

MacGregor became a forensic anthropologist almost by accident. She was born and raised in Ingham, north Queensland, but went to secondary school at Hurlstone Agricultural College in Glenfield, 40km southwest of Sydney CBD, because her father was an engineer for CSR and the family moved around a lot.

She completed a Bachelor of Science degree at the University of Queensland in 1993 before doing her honours there in Forensic Anatomy the following year.

“I was not intending to do this type of work. I went to uni looking at a science stream, in maths and chemistry. But when I got to uni, I liked the biological sciences more. I liked anatomy and physiology, and thought ‘that is really cool’. So I went down that path.”

She did her Masters of Forensic Science at Griffith University and has become one of the most highly trained experts in human and forensic osteology in the country, giving papers at international conferences.

After university, MacGregor joined the Queensland Police Service in 2000, and following a stint in general duties spent eight years in the Major Crime Unit. She is still a sworn officer and works part-time for the unit.

“You would come in and look at all types of crime scenes and analyse blood splatter, shoe outsole impressions, perform fire investigations and work with investigators to try and figure out what happened at a scene. There were a few big cases, I loved it. Every job is different,” she says.

The reality though, is nothing like television programs such as CSI or Bones (which is based on the novels of forensic anthropologist Kathy Reichs), where perfectly made-up forensic people are tossing quips, flirting and making dazzling observations about a corpse at a crime scene. Real scientists are a lot more serious.

“Normally when you walk up to a body, people are not dressed in beautiful clothes wearing designer suits with your hair down. That would contaminate a scene. You are gowned up. It’s more Prime Suspect than CSI.”

Eventually the shift work, the unpredictable nature of forensic crime scene work and missing out on family events all took a toll. And the tiny battered corpses.

“Children were really hard. What people do to their own children ... it just still puzzles me. You spend time in people’s houses, processing places where bad things happen. And sometimes you just wonder how people can do this or that. Nothing surprises me any more.”

Like anyone who has to give evidence in court against someone who might be going to jail for a long time, MacGregor is protective of her personal life. A lot of her work is confidential, and involves privileged information.

She is guarded when talking about her private life except to say that she has been married for 20 years and could not do this work without the support of her family and friends.

“I have a wonderful support system that keeps me very grounded.” She does not have children.

O

ne of the biggest cases for Queensland Police in recent years was that of Daniel Morcombe, the 13-year-old who was abducted from the Sunshine Coast in December 2003. The investigation remained open until Brett Peter Cowan was arrested in August 2011. MacGregor was part of the team that finally recovered Daniel’s remains after Cowan told undercover police where they located. Over the years she had looked at several possible burial sites.

“We had excavated and investigated a lot of remote sites. But because of the nature of this site we had to approach it in a certain way. It was a huge site, it had been eight years, a body might never be found. It was a hard search. We had to move it in a certain way, in a certain pattern to make sure we didn’t miss anything. We were on the site for a long time.”

They found remains. “We knew they were juvenile bones, it fit his age bracket. We had a good indication, but we really did need to run the DNA and other things. The scientist has to make sure, there was a possibility that there was another child.” But it was Daniel.

“You always remember that those bones might not have flesh but they still are a person. And that person deserves the dignity of looking after them to the very end, in the Morcombe case particularly. It was about finding him and then being able to give him back to his family,” MacGregor says.

Bones are always turning up and police often send MacGregor photographs of bones that have been found.

“After cyclones and big flooding events you get a lot of reports because stuff gets moved around or soil gets disturbed. About 90 per cent of the time they turn out to be animal remains,” she says.

“We send Donna photographs and she is able to tell us straight away if it is animal or human, whether it needs further examination,” Hansen says.

Brisbane Homicide Acting Superintendent Damien Hansen. Picture: Darren England.

What is also common are old Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander bones.

“If remains are determined to be pre-contact (before European contact) they are not allowed to be disturbed,” MacGregor says. “Skeletal features and contextual information, like if it is a known burial site, help make this determination. A panel including skeletal experts, local investigators working with traditional elders at the site, representatives from appropriate government agencies and coronial support officers determine a course of action. If they are in highly populated areas and could be interfered with then government agencies will liaise with the traditional elders to have them reburied. But in most cases we try not to disturb them.”

The ultimate cold cases involve MacGregor’s work with the army. She is a member of the Unrecovered War Casualties section in the Australian Army (UWC-A) and is often overseas as part of field teams with other specialists like odontologists, archaeologists and investigators. These teams are responsible for searching for and recovering the remains of unaccounted-for Australian servicemen and women. The unit operates in Papua New Guinea, Europe, East Timor and Indonesia, places where soldiers are still missing, lost in the confusion of war.

MacGregor has been working with them since 2009, mainly in PNG but has also been to France and Malaysia. The Unrecovered War Casualties website says more than 2000 soldiers are still unaccounted for in PNG from World War II. It is sombre work.

“Once we found an Australian flash (badge) on the shoulder of some remains we were recovering. We just stood looking at this flash. We were all very quiet.”

Most remains don’t have artefacts with them so the unit has to work out the ancestry as part of the biological profiling. The role of the anthropologist is to determine “the ancestry, sex, age and stature of the remains and, if possible, any trauma that might relate to the cause of death”.

Often the remains have been found by villagers, who the army negotiates with to be allowed to start digging. The unit uses war maps and diaries to help work out who they might be, forensic science and DNA from extended families to identify any remains.

“I am always mindful because a lot of the units (that were) in Papua New Guinea come from Brisbane and north Queensland, areas where I grew up,” she says.

It is hard, draining work. “But we owe these gentlemen the greatest debt of gratitude for their service and therefore to do the best job we can. All these men were prepared to lay down their lives. They volunteered and they went off to this territory because it was an Australian territory, to defend it. These guys deserve to have their stories finished and the last chapter of their lives told. At all times you are remembering that these are people who have a story and a family waiting for news or closure.”

When they are identified they are laid to rest with a full military funeral. Last June, Defence brought home the bodies of 33 servicemen and family members who had been interred at Terendak cemetery in Malaysia during the 1960s and 1970s. They arrived to a Federation guard at Richmond Air Base where their families were waiting. MacGregor had been involved in the disinterment, and she was among army personal waiting for them to arrive in Australia.

“It was a privilege to be present and a very moving experience. I hope that for these families there is some level of closure and sense of peace.”

I wonder if working with death makes her acutely aware of life. “It does ground you,” she says.

“You come home and you go, you know what my life is not so bad. You just realise that we are not here forever, so try to make a positive impact while you are here. Just love the people around you and make sure they know it. Make the most of every day, life is a gift.”

- This story was first published in June 2017