Bundaberg DFV perpetrator intervention program leading the way as DFV stretches police resources to breaking point

A ground-breaking program in Bundaberg is helping abusive men deal with the childhood trauma at the root of their own violence. Their stories are horrific but the approach is starting to shift the dial in a city that has reached breaking point.

Bundaberg

Don't miss out on the headlines from Bundaberg. Followed categories will be added to My News.

One rainy Tuesday night in suburban Bundaberg, a group of men slowly make their way into a row of featureless offices, distinguished only by a faded sign for a defunct mortgage broker.

As the men, aged from their early 20s to late 50s, gradually fill the plastic chairs arranged in a circle within one of the offices, gentle ribbing and banter ensues between some as others thumb their mobile phones in silence.

MORE NEWS: $53m hole: ‘Hamptons style’ wedding for Barbera patriarch

“How’s the farm?,” asks Ben*, a young man in his late 20s with curly red hair poking out from beneath a baseball cap.

Adam, a balding and burly former soldier, at 56-years-old the senior member of the group, responds with the laconic economy of language characteristic of Bundy.

“F--king wet mate,” he says.

While the conversation thus far is typical of any pub or sports field around the country, a sign on the wall titled ‘Group Agreement’ with principles including “be respectful”, “be honest, be open” and “what is said in the group stays in the group” portends weightier topics that go more often than not unspoken among gatherings of men.

The session that is about to begin is part of an intervention program for domestic and family violence perpetrators.

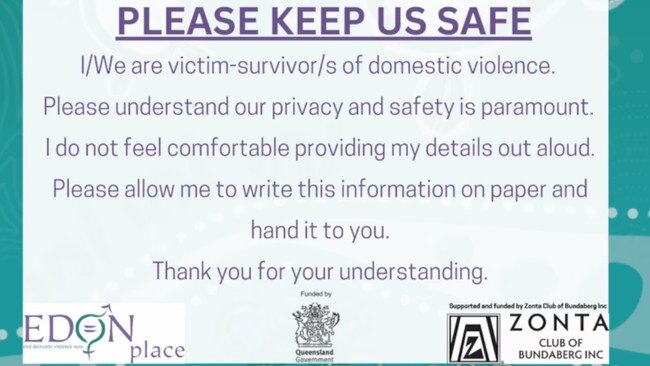

Called the ‘River of Cruelty’, the program run by local DFV support service EDON Place takes the participants through a series of guided discussions, 16 sessions in all, through which they examine the trauma experienced in their own lives and its influence on their own beliefs, attitudes and behaviour.

The 10 men who have taken their seats, with another joining remotely and appearing on a large screen in full view of the group, have come to the session in a variety of ways.

Some were mandated to attend by the courts after being convicted of DFV offences and others referred by police, while others are present entirely of their own volition, often men who were formerly forced to attend and, thanks to the positive changes the program has wrought in their lives and relationships, have now chosen to continue after fulfilling their obligations to the justice system.

Sheena, one of the course facilitators, gets the session underway by asking everyone to pick up cards representing various emotions - mad, sad, glad and afraid - and to tell the group in turn how they are feeling.

“I’m glad because I’ve been through almost seven days without a drama with the missus,” says Brett, a bespectacled, wiry man aged in his early 40s, a confession that is met with generous applause from the group.

“That’s a milestone for us, believe it or not.”

Another man named Carl, aged in his 30s, unshaven with a confident, engaging air, says he is glad for the way he had handled a potentially violent situation at a party he attended in the past week.

Provoked by another man, instead of responding with violence as he would have done in the past Carl says he invoked learnings from previous EDON Place sessions he describes as “muscle memory” to calm himself and move away from the situation.

“I knew how to respond without punching back,” Carl says.

“(The next morning) I woke up feeling centred, because you can relate to how it used to be.

“It’s strange how you can learn from the weirdest things.”

‘It’s at the point where we really need to do something’

Experts say DFV perpetrator intervention programs such as these are a critical battleground in halting the reproduction of violence that is traumatising victim-survivors and, at its worst, killing women and children and stretching police and DFV support services to crisis point.

Speaking at a community leaders’ forum called by Bundaberg police and EDON Place in February, Bundaberg Police Chief Inspector Grant Marcus outlined a shocking and sobering set of statistics showing that DFV incidents became the top call to service for Bundaberg police in 2022-23 for the first time.

From 2777 calls to DFV incidents in 2021-22, the number of calls rose by 30 per cent to reach 3604 in 2022-23.

And the pattern is showing no signs of abating with calls to DFV incidents in 2023-24 already exceeding prior years, with 3799 calls logged in the period up to March 31, 2024.

Apart from the untold psychological and physical harm inflicted on victims, Inspector Marcus said the burgeoning incidents of DFV was stretching police resources to the neglect of other crime fighting, with officers needing to devote 3-4 hours to each DFV call due to the complexity of many of the incidents.

“Domestic and family violence is a very complicated issue within our community, and to police it is just as complicated,” Inspector Marcus said.

“It takes a lot of time and a lot of effort, and as a result of that our resources are spending way more time on that, as opposed to spending time on other issues that we should be looking at.

“It’s at the point where we really need to do something about that in this community, so that policing can focus on other areas that are just as important.”

As the DFV offenders charged by police make their way through the justice system, the penalties imposed by the courts appear to have little effect in driving behavioural change.

Queensland Courts data shows there were 20,906 DFV charges lodged with courts across the state in 2022-23, a 36 per cent increase on the previous year and a staggering 97 per cent increase since 2018-19.

Despite this, and the imposition of penalties for contravening domestic violence orders including imprisonment, community service orders and fines, DVO breach offences are also on the rise, with 21,749 orders contravened across the state in 2022-23, the highest number on record and a 15 per cent increase on the previous year.

Behind this data huddles countless women in fear of being harmed again by their current or former partners, shockingly exemplified by the brutal alleged murder of Forbes child care worker Molly Ticehurst at the hands of her ex-boyfriend Daniel Billings in breach of an apprehended violence order earlier this month.

With legally enforced separation and punitive approaches failing to stem the burgeoning DFV crisis, the growing realisation that many DFV perpetrators are reproducing violence experienced through their own violent and traumatic childhoods has led to the growth of “trauma-informed” perpetrator intervention programs which seek to help perpetrators to understand the influence of that background on their beliefs, attitudes and behaviours and, crucially, hold them accountable for changing them.

One of Australia’s leading DFV researchers, Professor Silke Meyer from Griffith University’s criminology institute, said the shift to a more trauma-informed approach, already well advanced in the UK and USA, is gathering momentum in Australia.

Professor Meyer said most DFV perpetrator intervention programs in Australia were yet to adopt the trauma-informed approach, but those programs that have made the shift are “critical” to changing the behaviour of perpetrators with a background of trauma.

“We’re only beginning to see this shift and it is certainly not something incorporated into most programs,” she said.

“These approaches are one of several critical service system responses to men who use DFV. Not all men who use DFV have a trauma history so these approaches are critical when we work with men who do.”

Given the importance of perpetrator intervention programs in addressing the root cause of DFV, Professor Meyer said resourcing in this crucial area is chronically underfunded.

“A lack of funding is a constant roadblock to adequate DFV service delivery, including interventions with men who use violence,” she said.

“If we recognise that ending DFV requires effective interventions with those using violence rather than repeat crisis responses to victim-survivors we need to adequately resource this sector and support practitioners in obtaining relevant qualifications and skills to work with men who use violence. “

Crucially, the primary goal of the intervention programs themselves is not to provide counselling to the attendees, but to engender a sense of responsibility for their violent behaviour as DFV perpetrators.

“It’s important to be very clear that when we’re talking about a shift towards more trauma-informed approaches ... we’re talking about trauma-informed accountability work,” Professor Meyer said.

“This means accountability work with men as we know it in the traditional men’s behaviour change space combined with trauma-informed content and where appropriate therapeutic components.”

Bundaberg’s EDON Place is one of the few service providers to run a trauma-informed intervention program, with its ‘River of Cruelty’ curriculum going through various iterations since 2019.

The current program is modelled on the Family Peace Initiative, a United States intervention program that has been running since 2002 and delivers behavioural change program to DFV offenders in communities and correctional facilities in the state of Kansas.

The FPI website said the program is effective in reducing DFV offender recidivism, with a 2022 analysis of the success of the program in the Kansas county of Shawnee finding 85 per cent of offenders who attended the program had no further interaction with police over a six year period.

With a basis in Jungian psychology, one of the core aspects of the FPI program is to uncover the “shadow message”, its term for the often unconscious beliefs, frequently shaped in response to trauma, that underlie our behaviours and attitudes.

To exemplify the “shadow message” for the group, the EDON Place intervention program coordinator, Brett, who himself had a traumatic childhood at the hands of his father, tells the men of a humiliating incident in which his father rubbed Brett’s face in his own faeces when he was a child.

A short, softly spoken but intense man in his 50s, with the professional reserve of one who has been counselling for decades, Brett explained how he resorted to alcohol and drug use at the age of 11 as means of coping with feelings of being unwanted as a child.

He said the troubles with the law and relationship problems experienced through his youth and early adult life were essentially an exercise in affirming his “shadow message” of unworthiness.

“So when I was growing up, ... I felt unworthy, not good enough, useless,” Brett said to the group.

“So then I went out to prove that right.”

While he has now found peace within himself, Brett said latent feelings of unworthiness can still be triggered through mundane exchanges such as his wife telling him he hasn’t done the clothes washing, potentially leading to an argument until he catches the signs of his trauma-informed beliefs at play.

“It’s more about turning it around and actually seeing where it’s coming from,” he said.

The aim of the EDON Place program is to raise the men to a similar level of insight and accountability, such that they are able to understand the drivers of their violent behaviour and make choices that are not harmful to their partners and children.

“If the goal is that we can help these men move towards some accountability, a big part of that is understanding why we do the things that we do,” said Sheena, speaking after the conclusion of the session.

“And looking through that lens of trauma and looking at what those experiences have been as a child is a huge part of understanding why we’ve developed these defense mechanisms or coping strategies.”

Brett concurred, saying the program was more effective at enabling the men to come to grips with their beliefs and attitudes than more confrontational approaches.

“The trauma-informed (approach), I think that’s the way it should go,” he said.

“I’ve always had the argument, when did they become perpetrators?

“Because they were children once, who had violence perpetrated against them, and now we’re labelling them as perpetrators.

“I think if we can have that lens where we can see them as kids who have been traumatised themselves, then that will help.

“The non-judgemental approach builds a relationship with the guys (so) they can open up and talk about things.”

‘Dad done it, so there’s nothing wrong with it’

In response to a prompt from Sheena, the men give a long list of the ways in which cruelty can be inflicted upon children, with David, 42, talkative and wearing a Maroons jersey, writing them on a whiteboard.

Rape, bullying, physical violence, gaslighting and humiliation are among the 20-odd examples provided by the group, which clearly come from their own childhood experiences.

“All but one,” says Ben when Brett asks the group to count how many they had personally encountered.

Adam recounts a seminal incident when he was raped on a train as a 13-year-old boy.

“I told my Dad, he said ‘you were enticing him, you must have brought it on yourself’,” Adam says.

“Then I was black and f--king blue with broken ribs to boot.

“From that point on I couldn’t open up.”

David tells of when he came home from school and told his mother he was going out to footy training that evening.

He says his mother, who “had no drugs that day”, hit him in the face with a cricket bat, knocking him off the balcony and onto the windscreen of the car below.

The violence he routinely experienced as a child informed his own instinctive resort to violence first exhibited when he started drinking as an 18-year-old, David says.

“I sat down drinking at the pub ... and someone went behind me and clapped me on the shoulder and I just snapped. Before I knew it I had him on the ground and I was punching him, thinking ‘what’s going on’,” he says.

“All that emotion and shit that I went through came out in such an angry strange blur from my 20s onwards.”

When the discussion turns to how their childhood exposure to violence informs their current beliefs and attitudes about themselves, Adam cuts straight to the chase.

“I’m going to throw it out there, (it’s) the reason I’m here,” he says.

“Dad done it, so there’s nothing wrong with it, it’s normal.

“If you strike first, you control the situation. That’s the attitude.”

With the EDON Place program being a rolling format new participants are able to join at any stage, meaning the members all have widely varying levels of emotional insight and the corresponding vocabulary to describe their thoughts and feelings.

One new member named Ellis, a heavy-set man in his late 40s with straight black hair pulled into a ponytail, asks the group for help.

“I’m f--ked with words,” he says.

“What do you call it, if you believe and you think to yourself there’s nothing wrong with you, but there is?”

A chorus of suggestions from the group is heard, resolving to a consensus of “denial” as the term Ellis is looking for.

David, who is a longer-term participant in the program, seems to be edging towards the depth of insight that the course is aiming for.

“This kind of stuff doesn’t just start with one person, so where does this thing end? How do you break the cycle?,” he asks the group.

In response, Adam tells David “you’ll see how it’s historical, you see where it can change and where you’ve got control”.

‘You’re taught that you can change’

Today time runs out before the men can formulate their own “shadow messages”, but Sheena assures them they will pick it up next session and runs the group through a check out activity before they leave for the evening.

When it is his turn, Brett tells the group he has had a breakthrough, saying he realised his competitive nature is behind some of the regular arguments he is having with his partner.

“Now I’m understanding what she meant by ‘it’s not a competition’,” he says.

“She doesn’t want me to do anything, she just wants me to understand that she’s exhausted.”

David feels he has made progress simply through unburdening himself of his childhood experiences.

“All that stuff I went through that I told you guys, I haven’t even told my missus,” he says.

“It helps to get a load off your chest.”

Speaking after the conclusion of the session, Adam said the EDON Place program was the most effective of the many other interventions he had tried, including psychiatrist and psychological therapy and three other behavioural change programs.

After being kicked out of home for being physically violent to his partner’s children, Adam said he has repaired the relationship and will be marrying his partner later in the year, a transformation he said he owed to the EDON Place program.

MORE NEWS: Not horsing around: Major goals for fundraising event

“(With other programs) it was always that sense of blame,” he said.

“‘You’re violent’ was the angle that they took.

“This is the only course that has ever worked ... because it looks to the root cause of the problem, and you’re taught that you can change.

“But it’s a process, and it’s continuing.”

*All names of the River of Cruelty program participants have been changed to protect their identity.