Post-traumatic stress victim Dave Finney’s mother Julie-Ann calls for Royal Commission into his death

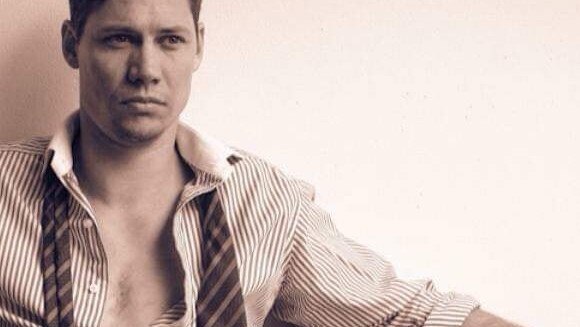

David Finney saved lives while risking his own. But as strong and as brave as he was, the former Navy sailor lost the battle of his life this year. His mother refuses to let his story end there.

East, Inner Suburbs & Hills

Don't miss out on the headlines from East, Inner Suburbs & Hills. Followed categories will be added to My News.

David Finney knew he was struggling.

The former Royal Australian Navy sailor had been fighting Post Traumatic Stress for a decade, and had twice been hospitalised while battling his mental demons after suicide attempts.

So when David, who had been medically discharged from the navy the previous year, felt himself spiralling out of control again, he wrote to the Australian Defence Force for help.

He asked to urgently see a psychiatrist. This was in October. The first available spot, he was told, was six months away.

Three months later, David Finney was dead. The young father was buried at Golden Grove cemetery on February 18 – the day after what would have been his 39th birthday.

His mother, Julie-Ann Finney, says she is now “completely destroyed”, but is determined that his death will not be in vain.

“David was a hero in real life, he was a hero in the services and he was a hero to me,” Julie-Ann, of Blair Athol says.

“Our family is broken … we’re just in pieces but I refuse to let David’s story end on February 1, 2019.

“I can do no more for my son but I can give him a legacy and work towards change for veterans who are struggling.”

Julie-Ann Finney is calling for a royal commission into Post Traumatic Stress in the military – and refuses to call the disease a disorder.

She says she is not angry at any individual but wants to challenge the protocols of the ADF to improve the system and have families better informed.

“I knew my son had PTS, I knew he was medically discharged but it was never supposed to be that I was going to lose my son,” she says.

“He was good at covering it all up and so is the navy. The only information I have now is what I am digging up among his papers.”

Julie-Ann is grateful for the support shown by numerous high-ranking officers who have called to express their condolence and “a beautiful letter” from the Chief of Navy.

But she remains disappointed in the lack of information about her son’s battle with Post Traumatic Stress.

“So many doors have been closed – but I am not going away,” she says.

“I am the mother of David Stafford Finney and I will protect his name and legacy with all I have from now until forever.”

The ADF invited Julie-Ann to Canberra this week, where she laid a wreath for her son during the playing of the Last Post at the Australian War Memorial on Tuesday.

Today, his image will be projected onto a big screen during the national Anzac Day memorial service at the same venue.

She is also using her time in Canberra to meet with several politicians, including ACT Attorney-General Gordon Ramsay, to discuss the plight of her son and other service men and women battling mental health demons.

“I want to reach for the stars in terms of getting change but whatever I can get I’ll take it,” she says.

“I don’t know what will become for this journey in David’s name but we should have a royal commission into PTS and the dreadful damage it is causing to families and the community.”

Julie-Ann was just 17, and already a mother of a two-year-old daughter, when David was born at Queen Victoria Maternity Hospital in Rose Park in 1980.

He grew up in Adelaide’s north east suburbs, went to Modbury South Primary and Modbury Heights High School, before enlisting in the navy at 18, where he spent almost 20 years before he was medically discharged in December 2017.

A prolific writer, recorder and broadcaster of his experiences, David traced the beginning of his mental decline to his young son, Kayne, dying in his arms after just 35 days from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in 2007.

That heartbreaking loss came on top of the trauma of his work in the navy, which sometimes involved rescuing refugees and recovering bodies, including children, from the ocean during a stint with ICAT, the Inter-Agency co-ordination Group against Trafficking in Persons.

He was also a veteran of the Iraq war, peacekeeping missions in Timor Leste (East Timor) and Bougainville.

He said coming face-to-face with the full circle of war, saving refugees desperate to flee their war-ravaged homes and especially those children whose parents had been killed in conflicts took an unmeasurable toll.

“You see the whole ugliness of humanity … It really hits you,” he said in an interview in 2018.

“My moral compass was knocked when I met kids whose families had been killed. I met soldiers, and refugees … I saw the bullet holes, blood, barbed wire.

“The sheer scale of the human tragedy was the refugees on the Australian shoreline. Some of them hadn’t eaten for days. If we hadn’t found them, they would have died. It makes you think ‘which ones didn’t we find?’

“Hearing their stories, seeing sick kids only a couple of years after I lost my son as well – all those things intertwined in my head and I couldn’t feel safe for anyone around me.”

A daughter, Kate, was born in 2008 but the mental stress of holding a machine gun one day and his newborn child the next played havoc with his mind and contributed to a marriage disintegration.

His recordings clearly indicate a man “living in a state of exhaustion” struggling with his responsibilities as a father, husband and active serviceman.

On his final Facebook post, timed to appear the day after his death he wrote: “I’m sorry I failed as a father.”

His mother says: “He failed at nothing – he just didn’t see it that way.”

In 2004, David received a naval commendation for his quick thinking actions putting out a significant fire on HMAS Tobruk which could have been catastrophic, jeopardising the safety of the ship and crew, had it spread.

The citation, signed by Rear Admiral, David Thomas, Maritime Commander Australia reads:

“Able Seaman Finney’s quick actions and courage while under pressure are an outstanding example to others and in the finest traditions of the Royal Australian Navy.”

And just three years ago, as a petty officer marine technician, he made international headlines in Hawaii.

While off duty fromHMAS Canberra in Hawaii as part of a RimPac – the world’s largest maritime exercise involving 25,000 people from 26 countries in the Pacific – David witnessed a man fall 5m from a pier in downtown Honolulu.

The victim struck his head as he fell and David stripped to his underwear and dived in to rescue the man from certain drowning.

“When I woke up in Queens Emergency Department, the nurse said I must have a guardian angel,” the lucky survivor Chad Gillingham told a local TV crew. “Then another nurse called out and said, ‘No! It was some Australian guy, I’m pretty sure guys don’t like being called angels’.

“Obviously I owe him my life.”

A humble David told the cameras that “anyone else would have done the same thing” but the beaming smile hid the ongoing emotional turmoil.

Finney wrote a blog called These Medals Aren’t Free where he detailed how his military career had come at a significant cost to himself and those he loved.

“I couldn’t defeat it, I was living in a state of exhaustion,” he wrote.

“It’s hard to put your hand up before it’s too late. There’s a loss of status, threat of being thrown off the ship when that’s what you love.”

Eventually in 2016 he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital ward full of other military personnel and first responders, police and ambulance officers, fire fighters and nurses, battling the same inner demons.

But on release he immediately returned to work – until the dam burst again.

While still in hospital, after a further attempt on his life in December 2017, Finney faced a charge of alcohol abuse.

“The ADF had information that David could not wear his uniform anymore because that triggered him to show breakdown behaviours,” Julie-Ann says.

“Yet the ADF regulations required that he get out of his hospital bed, dress in full uniform and be charged with alcohol misuse.

“He told me (it was like) he walked the gangplank alone over to the CO (Commanding Officer) who charged him.

“He sobbed for the entire walk and during the process that took place, he recounted that he was embarrassed and ashamed.

“He felt no one cared and no one would listen and there was no help.”

A few days later, on December 12, 2017, David was medically discharged from the navy.

He was still lying in a hospital bed, at St John of God at Richmond in Sydney, and would remain there for a further week, when the discharge was finalised.

“They (the navy) washed their hands and shifted him out … a man with serious mental illness,” his mother says.

“There was financial support – but that’s not what he needed.

“Centrelink will give you financial support but this was about life and death.”

Attempting to adjust to civilian life in Canberra, David worked at ways to help himself heal.

He joined an art course through Soldier On, an agency helping service personnel and their families to rebuild, and he continued work with Menslink as a mentor to young men and as a volunteer with Camp Quality, the children’s family cancer charity.

But in a last Instagram post, he detailed his agonies one final time:

“If it’s not one thing it’s something else. I’m running out of ways to forget!! I’m running out of ways to heal!!! I want more answers.

“Better solutions because sometimes I feel like I’m catching all the answers sometimes it’s like holding a fishing net in the rain. #imissmyboy #imissmyman #son #imnotstrongenough.”

A few hours later in the middle of the night, in Adelaide, Julie-Ann was woken with a loud knocking and a declaration it was a policeman at the door.

“Walking from my bedroom to the door I prayed they had come to arrest me,” she says, her hands trembling at the memory.

“I prayed this was all about me – that I’d done something wrong.

“As soon as I saw the policeman’s face I yelled at him: ‘You do not get to talk!’. I did that because I already knew when he got the words out of his mouth my life would be crushed forever.”

Initially in shock and then in hysterics Julie-Ann has little recollection of what happened over the next few hours.

She feels great sympathy for the policeman who was there on his own and waited with her until a friend was eventually called.

“I wasn’t in a position to be left alone and I wasn’t in a state to call anyone else,” she says.

“If I wasn’t focused on veterans’ issues with PTS I’d be raising the position of our first responders – it must have been just awful for him.”

She chose a burial over cremation because: “I couldn’t break David any further. He’d been broken enough.” She had the service filmed but cannot bear to watch it.

“I gave a eulogy but I just wasn’t there emotionally,” she says. “I can’t remember a thing about it I was so numb but will watch it one day. For now I’m putting my grief aside because David’s story needs to be told.”

On a cold morning in the build up to Anzac Day, Julie-Ann trembles with grief, more than cold as she talks about her new mission in life.

“I’m his mother but I don’t want to be this mother,” she says.

“I don’t want to be the mother who got that knock on the door by a police officer in the middle of the night, the mother who has to fight for a better system from the one that let down my son.

“But I don’t want another mother to feel like I do.

“I owe my son justice and I want change. We need to be able to access help immediately.

“We need education for family and friends to recognise signs. David was very good at hiding his feelings.

“He was a joker, a larrikin with a ready smile. If I had known for one minute I would have done all I could but for us there was no warning.”

As she works through her son’s military papers, Julie-Ann found an email he sent to the ADF in October last year, asking to urgently see a psychiatrist.

The response explained that with no psychiatrist taking on new Department of Veteran Affairs members available in the ACT, he’d have to go to NSW and the first available spot was April.

“Some days I just feel like ringing them up and telling them they can take him off the waiting list because he’s dead,” Julie-Ann says

“That’s an awful thing to say but that’s how I feel sometimes. There’s a free spot for someone else now if it isn’t too late.”

She refuses to refer to PTS as “a disorder”, instead calling it “an injury from his service”.

Julie Ann says her son was much loved and will be much missed.

“By telling his story it would be easy to focus on the PTS but I don’t want my son defined only by his problems and his final choices,” she says.

“He was so intelligent; he studied astrophysics did some university studies in physics and maths just for fun.

“He had a great career in the RAN, he made a great contribution, he was funny, tenacious, compassionate, the life of the party and a real man.

“He was my son. He did not want to die. He did not need to die. We need change now. I need my son.”

If you are concerned about the mental health of yourself or a loved one, seek support and information by calling:

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Beyondblue: 1300 224 636

MensLine: 1300 789 978

Veterans and Veterans Families Counselling Service: 1800 011 046

VVCS or Veterans Line After-Hours Crisis Counselling: 1800 011 046 (while overseas: +61 8 8241 4546)

Defence All Hours Support Line: 1800 628 036

Defence Family Helpline: 1800 624 608