Maralinga nuclear bomb test survivor reveals truth of what happened in the SA desert

Only a handful of members are left of an Australian Army unit that built the camps at the top secret Maralinga nuclear bomb facility — most have died of cancer. More than 60 years on, a survivor finally reveals their story.

East, Inner Suburbs & Hills

Don't miss out on the headlines from East, Inner Suburbs & Hills. Followed categories will be added to My News.

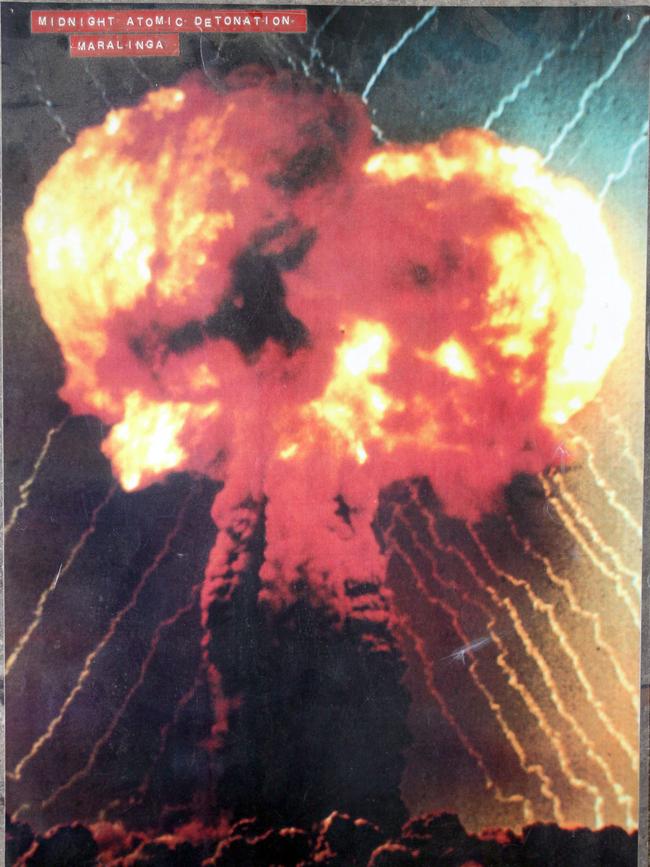

The nuclear bomb tests, under British Government control, at Maralinga in far west South Australia in the 1950s were conducted at the highest level of secrecy. But they had thousands of witnesses. Most were Australian servicemen, innocently used as guinea pigs and exposed to deadly radiation. Craig Cook talks to a survivor, one of the last of a group of men who built the Maralinga camp as part of 23 Construction Squadron and watched in awe as the bombs were exploded, little knowing they were risking their lives and the futures of their children.

*****

Tony Spruzen knew the drill at the top secret Maralinga facility in the South Australian desert in the spring of 1956.

Just like hundreds of others at the nuclear site at 11-mile camp during Operation Buffalo, he was told to turn his back and cover his eyes to protect himself from the gigantic glare of the exploding atomic bomb.

What they didn’t tell the Australian Army sapper was, at the moment of the flash of detonation, he would see the bones of his hand through his tightly shut eyelids.

“It was like a massive x-ray,” Tony, 83, from Glengowrie says. ‘Unlike anything I’d ever known before.”

“Then we all turned around to see this mushroom cloud climbing into the sky. The next thing was the blast. The boom was deafening…and then the wind came about thirty seconds after that blowing dust and soil and debris all over us.”

It was early morning, late September and standing there in the rising heat of the day, the 20 year-old felt the awe of the moment, history in the making, and no sense of terror or trepidation.

Spruzen, originally from Victoria and a carpenter by trade, enlisted in the Army at just 16.

Four year later he was at Maralinga as part of a detachment of 23 Construction Squadron, an acclaimed unit of the Royal Australian Engineers and exclusively raised in South Australia.

Around 40 young men were selected from the unit to build a desert tent camp with cook houses and latrines for the Commonwealth military ‘high-ups’ who were having their first look at the impact of the devastating nuclear weapon.

Around 200km from the ocean, the tent city gained the facetious name of the ‘Sea View Holiday Camp’.

“It was an adventure…we were all excited,” he recalls.

“A lot of young single guys together and we had some fun.”

The lads knew it was serious too as this was a hush-hush operation. They weren’t even allowed to take a camera along for snapshots so Spruzen has no personal photos from Maralinga.

But he does have a terrible reminder of his three months spent in far western South Australia.

“Of the 40 men who went up with me I only know of three of us still around,” he says. “The rest have all died - many from cancers.”

The first Maralinga bomb, Buffalo 1, with the nickname One Tree, was detonated after being dropped from a 31m high tower.

At 15 kiloton it was the same size as Little Boy, the bomb dropped by the US air force that demolished the Japanese city of Hiroshima in August 1945, killing more than 100,000 instantly and tens of thousands slowly in the aftermath from burns and radiation poisoning.

A week after One Tree, on October 6, 1956, Spruzen witnessed the detonation of Buffalo 2, named Marcoo.

The bomb was only a tenth the size of One Tree but this time was detonated directly above and just under the ground.

“The bomb was in an amphitheatre of hills and we were far closer to that one, maybe only 200 yards away,” he remembers.

“We were close enough to see the trenches with dummy soldiers in them holding rifles and fake aeroplanes and tanks used to test the blast effect.

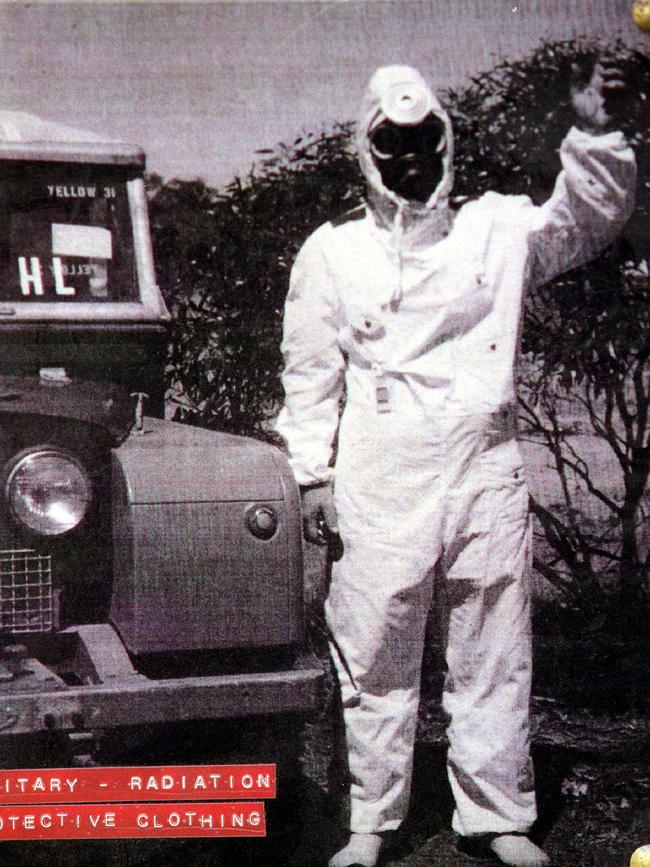

“And we could see the scientists walking around in their white suits checking out the site before and afterwards but we were just in khaki shorts and short sleeved shorts. Even the dignitaries had no protection.”

Every hour, from five hours out, an elaborate PA system across the complex announced the timing of the bomb detonation.

In the final 30 seconds, and with a rising and excited inclination, the voice on the PA dramatically counted….ten, nine, eight…down to zero.

When Marcoo exploded at 7am it only took a few seconds for a heavy shower of dust to descend on the witnesses.

“We had this large piece of litmus paper attached to our shirts,” Spruzen recalls.

“They said, keep an eye on that and if it changes to pink come and see us. Well it turned pink for every one of us.

“Had I have known what I know now I wouldn’t have been so close.”

Transferred to Sydney on a training course, Spruzen missed the final two detonations at Maralinga that year: on October 11, 1956, Buffalo 3 (Kite) was released by a Royal Air Force Vickers Valiant bomber, the first drop of a British nuclear weapon from an aircraft; and then on October 22, and again dropped from the 31m tower, (Buffalo 4) Breakaway exploded.

There were a total of seven nuclear desert tests at Maralinga performed during Operations Buffalo and Antler.

The 1985 McClelland Royal Commission heavily criticised the detonations, declaring the weather conditions were inappropriate and led to the widespread scattering of radioactive material.

The radioactive cloud from Buffalo 1 reached more than 11,000m into the air and with a northerly wind blowing radioactivity was detected across Adelaide.

Radioactive dust clouds from other bombs were detected in Northern Territory, Queensland and across New South Wales, as far away as Sydney, 2500km from Maralinga.

Around 12,000 Australian servicemen served at British nuclear test sites in the southern hemisphere between 1952 and 1963.

In recent years, the British Government’s claim that they never used humans “for guinea pig-type experiments” in nuclear weapons trials in Australia has been revealed to be a lie.

Tony Spruzen has struggled to come to terms with being placed in danger by his own government who had full knowledge of the consequences of exposure to radiation.

“Once we all found out later what we’d been exposed to at Maralinga it makes you very angry,” he says.

“We believed them when we were told we would be safe — but we haven’t been.”

Spruzen met his wife Shirley, the daughter of an army veteran, in Adelaide where they settled after marriage in June 1960. He left the army seven months later to work in civil construction. He thought his Maralinga days were well behind him but soon after they came to haunt him.

In the first four years of marriage, the couple agonisingly suffered six miscarriages, including twins.

Alarm bells started ringing when he was sent a survey from Veterans Affairs asking about his general health and, specifically his history of cancers.

“It turned out those involved in the atomic tests had a 30 per cent higher chance than getting cancers than the general public,” he says.

“Most of those got them within the first five years and a majority of those were dead before a decade had passed.”

Spruzen, who eventually had three children with Shirley, didn’t get cancer at that time, although he has since had several melanomas removed.

But when his son was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia at the age of 41, he wondered about the possibility of faulty genes, damaged by exposure to radiation, as has been documented in Japanese survivors of the atomic bombs, jumping a generation.

“My son was told by the QEH (Queen Elizabeth Hospital) there was nothing could be done for him but we went up to Queensland and after a bone marrow transfer from his sister he survived,” he adds.

“A decade on he’s working as strong as he has but I don’t think his condition was a coincidence given my history.

“There’s been nothing (compensation) for those of us who were there although they gave us a white card for our cancers and now we have a (full health) gold card.”

Ken Daly, President Royal Australian Engineers Association says it is the least the men, who literally put their bodies on the line, deserve.

“You get these young men, aged around 25-30, with a history of exposure to radiation, coming down with cancers in those numbers and you just know what has caused it,” he says.

“Many died within a few years of being exposed to the fallout and many passed on generational health problems and birth defects to their children.”

Mr Daly, who was based at Warradale Barracks for 15 years, where 23 Construction was based until being disbanded in the early 1960s, hadn’t heard of the Squadron until around five years ago.

Since then he has been central to the group gaining due recognition.

In its earliest days the Squadron, with a strength of eight officers and 160 in other ranks, built the El Alamein Army Reserve camp, part of which later became the Baxter Detention Centre, outside of Port Augusta.

It also assisted the South Australian community by providing aid during bush fires, the grasshopper plague of 1955, and significant infrastructure construction.

During the record flood of 1956, while those squad members were at Maralinga, the rest of 23 Construction were out sandbagging River Murray towns and then cleaning up after the water receded.

In 2011, the Royal Australian Engineers constructed a memorial at Warradale to all who have served in its ranks.

This year a bronzed engineer’s slouch hat, of actual size, by Western Australian sculptor and former army engineer Ron Gomboc will be incorporated into the memorial.

“The hat will be mounted on the memorial in such a way it will look like it’s suspended in mid-air,” Daly adds.

“It acknowledges the ultimate sacrifice of the more than 1250 engineers who died in World War I and the remarkable service and sacrifice of 23 Construction Squadron that has never been recognised before.”

The slouch hat, costing $6,000 and one of only six to have been cast, will be unveiled during a service at Warradale Barracks at midday on Sunday April 28.

Contact Ken Daly at dailydouble@bigpond.com for further details.