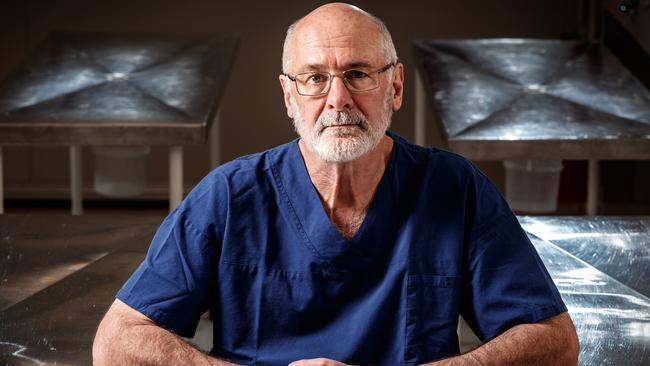

Senior forensic pathologist Roger Byard explains how an SA murder led to working with victims of acid attacks

Adelaide’s ‘Guardian of the Dead’ has revealed the one “cruel, evil” murder which still haunts him, and the work he does now to help ease the nightmares.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Adelaide’s “Guardian of the Dead” has revealed the one shockingly cruel case which still haunts him – and how working to prevent devastating acid attacks on women has helped him deal with it.

A trained doctor, Professor Roger Byard has seen it all.

A senior specialist forensic pathologist at Forensic Science SA, his early work involved autopsies to work out why so many babies were dying from SIDS.

Then in the 1990s came the Snowtown Murders – 11 people murdered by three serial killers. His job was to take the stinking, mutilated bodies out of the barrels.

In 2002 came the Bali bombings – Professor Byard was on site, trawling through the rubble trying to identify victims by picking up fragments of muscle because in most cases the skin was so burnt it was indistinguishable from the rest of the debris.

But after close to 40 years conducting autopsies came one case that shook him like another: Jasmeen Kaur.

She was the 21-year-old nurse who was stalked, bound with tape and cable ties and buried alive at Moralana Creek, near Hawker in the Flinders Ranges.

The murderer was her ex-boyfriend, who couldn’t accept that she ended the relationship with him.

“I still think about her a lot,” Professor Byard said.

“I think the thing about Jasmine was, she was a very caring person.

“She was in that boot for five hours. This outraged me.

“Then to die like that – buried alive – one of the worst ways to die.”

When Tarikjot Singh was in court to be sentenced, Professor Byard – for the first time in his distinguished career – went to watch the sentencing.

Asked his impressions of Singh that day, Professor Byard said “he looked very ordinary”.

“You know, that was the extraordinary thing, which is sort of worrying when you think of somebody as banal-appearing,” he said.

The crime, that still plays on his mind, led him to study another type of horrific violence which he says comes from “that same male need to control”.

He met Navpreet Kaur, a young lawyer from Amritsar in India’s north, at a conference.

She had dedicated her PhD and her life to trying to stop Indian women becoming victims of horrifying acid attacks daily.

Then it was through Dr Kaur that he met Neetu Mahor.

Neetu had corrosive acid deliberately thrown on her when she was three, because her father was angry that his wife had not given birth to any boys.

“Words fail. I mean, when I met Neetu, she’s hideously scarred and deformed, so has suffered so much but she’s got this energy. So after about half an hour, you don’t even see the scars. Extraordinary.”

Professor Byard’s research with Dr Navpreet Kaur looked at education in India and how skin grafts can be used on victims.

His work has made it into Indian general practice journals.

It ties in with the very reason he fell in love with pathology – “the preventative side of it … rather than just doing an autopsy and writing a report, you think, well, what could I do to prevent this happening?”