Guardians of the Dead: Inside the intriguing world of forensic pathology

Dealing with dead people can take it’s toll but, death is just a part of life, says forensic pathologist Professor Roger Byard in a new podcast from The Advertiser and the University of Adelaide. Listen to episode 1 here.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Death doesn’t become easier to deal with. Even after thousands of autopsies. If anything, Professor Roger Byard, senior specialist forensic pathologist at Forensic Science SA, says death becomes more difficult as you develop a deeper understanding of the grief it causes.

Byard sees it especially in the emotional waves caused by the death of the young. He is a world-leading expert in pediatric forensics and, in particular, sudden infant death syndrome. Over the years he’s had hundreds of conversations with parents heartbroken from the loss of a child.

“The baby cases and the child cases, and pediatric forensics is my area, but they’re getting tougher now because I do understand the tragedy and I’ve seen so many parents – talked to so many parents,” he says. “Whereas, when I was younger I was thinking ‘okay, really interesting case, find the cause of death here’.”

Byard says these conversations with parents struggling with the greatest loss imaginable are the “most human kind of interaction”.

“Sitting there with parents who have lost a child and just eyeballing them and saying this is terrible.”

Byard’s career as a pathologist spans almost 40 years and more than 6000 autopsies. The chair of pathology at Adelaide University, talks about his career in death, in a new podcast series, Guardians of the Dead, launched by The Advertiser and the University of Adelaide.

LISTEN: GUARDIANS OF THE DEAD EPISODE 1

Byard has seen death in all its forms, from working on high-profile cases such as Snowtown and the Bali bombings, to natural disasters such as the Boxing Day tsunami of 2004, which killed 230,000 people in 13 countries, including Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and India.

The eight podcast episodes will cover many aspects of Byard’s career, including the case of 15-year-old Samantha O’Reilly who was murdered in 2003, victim identification, and animals in forensics, and even bushrangers and weird ways to die.

A guardian of the dead is how the 66-year-old Byard describes himself.

“We are the last doctor this person will see,” is his rationale.

As a society, Byard doesn’t think we talk enough about death, scared off perhaps by the lead up to the moment where life ends. Of the pain and suffering and disease that causes the death itself. He says it makes us more “fearful about death than in previous ages”.

“I think the process, how you get there, that may be scary, but death is just a part of life,” he says. “We’ve divorced ourselves from it. We don’t put grandma on the kitchen table and have the wake and say goodbye and the proper send off. She’ll be whisked away, she’ll be put in the coffin and maybe just sent to the crematorium.”

Byard acknowledges pathology is an “odd” specialty. It also wasn’t his first choice within the broader medical field.

He grew up in rural Tasmania and graduated in medicine from the University of Tasmania in 1978. He did five years of clinical medicine and trained in family practice to become a GP and contemplated emergency medicine.

He decided being a GP was “too difficult”.

“When I say that to GPs, they think I am being patronising. I’m not. It’s actually right on the coalface, it’s a very difficult job. They don’t know whether it’s going to be something that’s going to kill somebody tomorrow, or whether it’s just something really minor.”

LISTEN: GUARDIANS OF THE DEAD - TALES FROM THE MORTUARY

Byard trained in family practice at McMaster University in Canada and returned there with the intent to study emergency medicine. Which is where he was sidetracked into pathology. According to Byard, he “couldn’t find a job and ended up in pathology”.

Apparently, pathology is not that highly regarded by some in the world of medicine.

“It’s regarded the shallow end of the gene pool,” Byard says. “Because it’s very physical, you go into death scenes and police and the courts.”

But there is also a lot more to it.

“When I got into pathology I realised just how academically challenging it is,” he says. “First of all, I couldn’t work out if we know what causes diseases, why can’t we stop them?”

Byard says in pathology you are constantly challenging yourself, or hypothesis testing, as he calls it. He asks hypothetically: “This old fella dropped dead mowing the lawn. Why did he die yesterday, not two weeks ago?”

He remembers well his first autopsy. He met the patient beforehand. Byard was a medical registrar at Hobart’s Repatriation Hospital where he met a man with terminal lung cancer. Byard told him he didn’t have long to live and that there would also be an autopsy, which he would conduct.

“He just looked at me and he sat back in his bed and he said, ‘that’s okay, son, you’ll be all right’. And it was like a blessing on my career.

“And so that was my first autopsy. I looked after him in life and I looked after him in death. I was very honoured to be trusted by him like that.”

Byard also remembers his first pediatric autopsy – a little girl in Canada called Genevieve who died from leukaemia complications. He says having a connection with the dead helps him deal with a job that, to most, would be too grim to contemplate.

“I do counselling with families, often with families with lost kids to talk to them about what’s happened,” he says. “And often, it’s not so much what happened, it’s (letting them know) who the person was who looked after their baby or their child.

“You can tell them that this is not (just) a case, this is a terrible tragedy, and everybody feels it.”

There is also a comfort for families in understanding why people died. That you can supply at least some of the answers, that death was inevitable and their loved one had been given the best possible medical treatment.

Byard says it’s also about finding ways to stop similar deaths in the future. “People say to me ‘oh, God, pediatric pathology, forensic pathology, how do you do it?’ You do it because you want to find answers and make a difference,” he says.

“It’s not a job it’s a vocation. And I think that’s the only way you can approach it because you see such tragedies.”

Byard’s work in sudden infant death syndrome and sudden deaths in the young has been acclaimed internationally. Last year, he was ranked in the top 2 per cent of scientists around the world by the prestigious Stanford University in the US and No.2 in legal and forensic medicine.

“The thing about pediatric work, I mean they’re babies and they’re kids, you know, they deserve to live,” he says.

The raw grief of the parents is also something at the forefront of his mind.

“Families going in and finding an apparently perfectly healthy baby dead. How do you get over that?” he asks. “People say have another baby, you will get over it. That’s rubbish. You just get better at dealing with it.”

Thankfully, the number of babies dying from SIDS is falling and Byard believes his research into substance P will lower numbers further. It had already been established that babies sleeping face down were at greater risk of SIDS.

The question, Byard asked, was why the babies didn’t lift their heads up when in distress and save themselves. The answer was they couldn’t. That an abnormality in the brain stem meant a deficiency of substance P, leaving them unable to control head and neck movement properly. “So, I think we explain why some babies are at risk. Sleeping face down and they can’t get out of it, so that’s very exciting and useful.”

But to live in among all that death does sometimes takes a toll. Byard says there is a comfort in the process, in the science and the medicine, but sometimes it’s inevitable that cases will get to you.

The 2004 Boxing Day tsunami was, unsurprisingly, one of those occasions. A 9.1 earthquake off the northern tip of the Indonesian island of Sumatra, triggered waves of more than 30m travelling at more than 800km/h across the Indian Ocean.

Byard was sent to Thailand where almost 5400 people, including 2000 foreign tourists, were killed.

“The tsunami, I found that incredibly challenging. There’s just so many dead children. All these happy young families having the time of their lives and just suddenly wiped out. It was a scale of what was just unimaginable. I mean, the first day I arrived, there were trucks turning up full of dead and decomposing bodies.”

Byard says despite the enormity of the tragedy, it was not until he returned home that it really hit him.

“I tell this to students,” he says. “I was just standing in the sunroom and burst into tears.”

The story makes his students uncomfortable “because he’s a pathologist, a professional pathologist talking about emotions”. But he tells them the tears are a normal human response to an extreme situation.

“You know I’ve got the right to grieve these people, because I saw them, and looked after them,” is what he tells them.

How to process that grief is another matter. Byard has recently written an editorial on post-traumatic stress disorder.

“What do we do, day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year, we examine dead bodies … we go to scenes where we’re picking up pieces of bodies,” he says. “We’re examining it in incredible detail, we’re coming up with causes of death in court.”

When he returned from the tsunami, Byard was offered counselling. He decided it wasn’t for him, that there were better ways to deal with the trauma.

In his recent editorial, he suggests perhaps PTSD in forensic pathologists should be studied further, but he also says “if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen. I just think that you’ve got to realise that it’s important”.

“Colleagues are actually most useful,” he says. “I was the chief pathologist when I came back from the tsunami and they said ‘everyone who went needs to get counselling’ and really, I don’t think the counsellors get it because it’s outside their experience. Whereas you talk to colleagues and debrief that way, talk to friends.”

Or there is always the non-human, non-judgmental option.

“I talk to my dog, Lucy, she understands things very well, thinks I’m really, really witty and humorous and lovely. That’s perfect.”

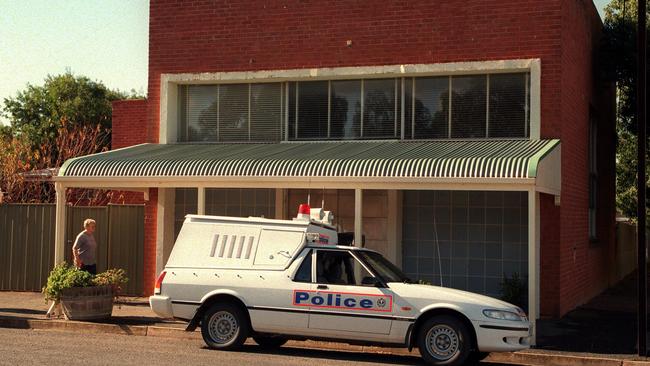

Is there a difference dealing with the dead from a natural disaster such as the tsunami to those who die from acts of other humans? Byard examined the remains of one of the Bali bombers and was intimately involved with the bodies in the barrels case where eight bodies were found in six barrels in an abandoned bank vault in Snowtown, a small town 150km north of Adelaide. There would eventually be 11 victims in the series of murders.

In May 1999, it was Byard’s first week as on-call pathologist. He received a call at 9pm on a Thursday night from major crime head Paul Schramm who told him: “It’s a bit strange really, I’m in a little place called Snowtown in a bank vault and it’s lined by plastic and there are all these barrels”. Byard asked if it was a hydroponic operation. He was told “no, it doesn’t smell like it”.

Byard advised Schramm to take a lid off a barrel. “And if there’s a foot give us a call back,” he says. “Typical black humour, that was the last thing I was thinking. Ten minutes later, he calls back saying actually there is two feet.”

Byard gave evidence in what became known as the Snowtown trials. He was in court with the accused, and subsequently convicted, murderers John Bunting, Robert Wagner and James Vlassakis.

“Snowtown was such a meticulous process you get supported by the process,” he says.

When it comes to criminal trials, Byard says he doesn’t make judgments about the accused. After all, he only knows the bit of the case he’s testifying about.

“When there’s a perpetrator and you know victims and the families you do learn to be dispassionate,” he says. “My role is to actually just provide information so that people can actually work with that.

“It’s just your professional training. The important thing is that it’s not about them or me. This is about the court and getting information to people.

“So when I provide my information, I’m providing it to the jury, to the lawyers, to the judge, to the accused. It’s information that shouldn’t be biased by anything. Everyone’s got a right to it.”

It’s also a skill to translate what can be highly technical medical information into a form where a non-expert on a jury can digest it and make a judgment on it.

“If you can’t explain it in terms people can understand, I don’t think you understand it yourself. So … you’re eyeballing people to see if they get it.”

Forensic pathologists became a bit cool there for a while.

But Byard has no time for shows like CSI, Bones, Rizzoli and Isles, Harrow, Silent Witness (or Witless Silence as Byard calls it).

His only weakness is Inspector Rex, where the hero is a dog.

He also jokingly takes issue with the characterisation of his profession.

“So, what is it all these forensic pathologists on TV – bespeckled balding old guys with weird sense of humour,” he asks with a smile, knowing full well that’s how many could describe him.

Byard says the infamy hasn’t attracted any more students to the profession. But when those that do show an interest ask how long it takes to become a pathologist, he tells them: “It takes six years of medicine, four years of training, then, you know, this and this. I did my last degree last year. So 40 years. They pale.”

Despite the particular nature of the profession, and the celluloid portrayals of pathologists, Byard says there are no consistent characteristics of people who dive into pathology, except perhaps they require a challenge.

“It’s not a very popular area, but we are getting some very good quality, young people,” he says. “And I think that the academic side of it helps, because they can see that there’s intellectual rewards from doing this work.”

Very few have seen as much death up close as Roger Byard. But what happens next? What happens when the last breath is taken, when the heart has pumped for the last time?

Byard believes something of us lives on, even if he is not religious in a conventional sense.

“I’ve got a very basic approach,” he says. “I think there’s a life force that goes through us all. Because to me, there’s a lot of difference between a baby and a brick. Call me simplistic. They seem to be different.

“I regard myself as like this eddy in the river of life. It’s a distinct eddy until it goes still. (Once it goes still it remains) part of the life force, and there, but not as it was. So, yeah, it’s a simplistic religion maybe, but it keeps me going.

“It means I don’t have to go to mass every Sunday or get up and worship the sun at five o’clock every morning.”

A new episode of the Guardians of the Dead podcast will be published on Advertiser.com.au every Monday and Friday for the duration of the series.