War on suicide: Afghanistan veterans fight insidious killer

How war heroes are using mobile phones and social media fight a new enemy looming large on the home front.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Jonny Spicer suddenly hit down hard on the brakes. The car was now motionless in the middle of a suburban road north of Adelaide. The veteran soldier sat petrified and his two sons were bewildered in the back seat. Panicked, his heart rate was skyrocketing. They had been on their way to the local store and his eye caught a glimpse of something familiar by the roadside.

It was a bright yellow palm cooking oil container sitting by the side of the road. It was the same type of container he had seen many times in Afghanistan, where they were regularly used in the construction of roadside IEDs – improvised explosive devices. “They were filled with explosives set up to detonate through a pressure plate or remotely,” says the ex-army engineer. “I froze for a while – I can’t remember how long. The kids eventually snapped me out of it.”

That was two years ago and almost a decade after the first of two deployments to Afghanistan. Spicer, now 42, was diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in 2013. The Gawler father of four says the telltale signs – hyper-vigilance, insomnia, anxiety, irritability, and emotional detachment – began soon after he first returned from Afghanistan in 2010.

“I knew that I wasn’t the same – I was always angry; I wasn’t motivated or passionate; I had zero interest; I had panic attacks; found myself gasping for air – I just felt dead inside,” he says. “At my worst, I just didn’t want to be here anymore.”

Spicer was trained as an army engineer. Engineers are responsible for protecting troops by clearing routes of explosives, and are also tasked with building and repairing fortifications and bases in hostile territory.

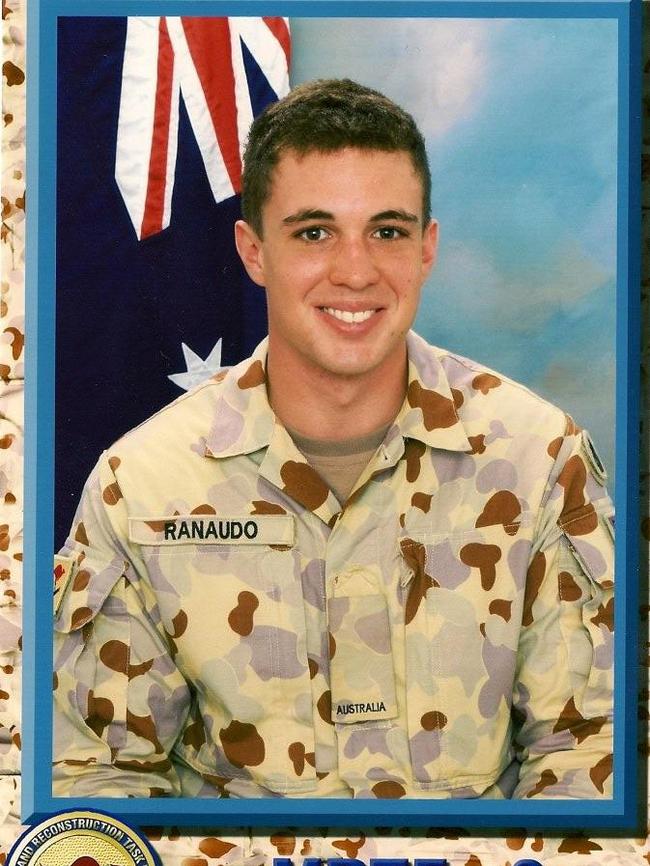

“It’s hard to say how many we lost, but the close ones, I remember every day,” he says. Among them was 22-year-old Private Benjamin Ranaudo, who was killed by an IED on July 18, 2009.

When the explosive detonated, Spicer was about 500m away on overwatch duty – the process of watching another group of soldiers from a higher advantage point and giving support if necessary.

“We saw and heard the blast, followed by the hive of activity over the radio, prior to the casevac (evacuation of casualties by air) arriving,” Spicer says. Ranaudo died instantly and another soldier was badly injured.

Almost a year later, 25-year-old Darren Smith, who was once an Adelaide Army Reservist who Spicer encouraged to join the regular Army Engineer Corp, was killed by an IED alongside his explosives detection dog Herbie and fellow engineer Jacob Moerland in the Oruzgan province. It’s a death Spicer continues to claim some responsibility.

Australia’s involvement in Afghanistan is now significantly scaled back. But the body count continues. Spicer says he’s lost count of the mates who’ve died – the majority from suicide. He says suicide is a very real problem happening now, but its very nature means it remains a cultural taboo that needs to be exposed without fear or prejudice.

“People are still taking their own lives – these are friends of ours – it is a weekly bloody battle,” he says.

It’s one of the reasons why Spicer and former 35-year-old army engineer Tyson “Pottsy” Potter felt they needed to do something about it. Potter, a father of two from Darlington, was diagnosed with PTSD two years after deploying to Afghanistan in 2013. Despite their own mental health scars, Spicer and Potter began a national operation in 2018 to save their mates and hunt down the homeland enemy of suicide through social media. Their campaign started around the same time Potter was involved in searching for a close veteran friend who went missing in Adelaide.

“We were out searching for him for days. He was distressed and tired, and he would have committed suicide – that was definitely the plan,” Potter says.

They found him before he could hurt himself. Armed with social media and mobile phones, the Adelaide duo, who met in 2014 after their overseas deployments, established a Facebook page designed to help veterans keep watch on their mates.

Spicer is the president of the Veterans Motorcycle Club Adelaide chapter and Potter is vice-president. The pair created a closed Facebook page, which they called VMC Overwatch, for members across Australia. The page is part of a growing Overwatch movement where veterans are banding together to help their mates.

The VMC Overwatch page now boasts more than 200 members, 50 in SA, from more than 30 chapters across every state and territory.

When Spicer and Potter receive a post or a text of a veteran in crisis or showing mental health warning signs, they pull together a team of first responders and observers. They reach out to other Overwatch pages for help too. The message or phone call almost always comes from a concerned relative, friend or veteran and a search can start at any moment of the day or night.

“Only last month, I had a worried wife at my doorstep,” Potter says. Potter and Spicer have been involved in dozens of searches for at-risk veterans missing across the country and many much closer to home.

“Once we get the message, then we will nominate a main contact to start liaising with police and with the veteran’s family,” Potter says. “We then establish who, from various Overwatch pages, know the veteran and which veterans are free to form a search party. Once we have that information-exchange process set up, teams will go north, south, east and west, and search for the veteran. We start knocking on doors.

“We have contacts with pubs, clubs, security companies and we show them photos and they help keep a look out for our guy. Sometimes they’re spotted on CCTV or the police find them. Sometimes they call in to let us know they’re OK, or they come back home or they bring themselves to hospital for help.

“We can be out searching for days. The longest I’ve been out searching is three days – coming home for sleep. Due to work schedules, usually we can have at least one person on the ground at all times.”

Sometimes, responders can be among the first to arrive. “I’ve talked down a veteran from a noose,” Potter says.

More than two thirds are found in time. But it’s not an easy task.

“The notifications we get are almost always second-hand because vets have a culture of not asking for help,” Potter says.

“The scary thing with these guys is that they have all been indoctrinated to not put up their hand for help,” Spicer adds. “Because in the military, if you are the weakest link, you will take the team down and you will cost lives. You’re taught that you are letting your team down. They’ll remove you from your unit and make an example of you. You become an outcast, and that’s the last thing you need when you’re struggling – to be taken away from your family. So no-one ever asks for help again.”

And once the veteran goes to ground, they can be hard to find, because of their military training to go undetected.

“So if they don’t want to be found, they won’t,” Potter says. “Often they just get in the car and go bush. We try and follow their patterns, where they were last seen, where they frequent and I try and think, ‘Where would I go?’”

One of the sombre searches Potter recalls most was scouring bushland north of Adelaide for a veteran who was never found.

“I found his service dog and his swag left behind. It was a sign of desperation and a resolution that he just didn’t want to come back,” he says.

Potter joined the Army in 2012. A year later he was in Afghanistan. He still carries the wounds and has had some dark times too. “There was no off switch,” he says of the hyper-vigilance constantly triggered by the PTSD. “I still experience it now – I am constantly searching for a threat and constantly assessing.”

His assistance dog Arnie – always by his side – helps calm the PTSD symptoms. And despite all the worry and anxiety that searching for those in need provokes, Potter says it is the right thing to do.

“A lot of them are left in the dark. They fall through the gaps. We need to look out for each other,” Spicer says. “We have a powerful support network. Veterans have always looked after veterans.”

“It’s a brotherhood,” Potter says. “The VMC Overwatch is just another tool we have if it’s needed to reach out and get information shared as quickly as we can if a brother is in need.

“The VMC is a big family and after a few years you get to know members all over Australia. A couple of phone calls and help can be dispatched immediately if needed.”

The VMC Overwatch also links veterans with mental health and Department of Veteran Affairs (DVA) services, as well as advocates who help navigate through the “merry-go-round” of documentation and examinations needed to claim DVA payments for medical treatment, income replacement, permanent impairment compensation and for rehabilitation programs. Spicer’s claim for permanent impairment after sustaining a knee injury in Afghanistan took three years.

“It was terrible,” Spicer says of the long wait. “You just keep battling on until it gets to a point where you’re just at breaking point.” Discharged from the army, while awaiting his claim, Spicer had to support his four children and wife, and took up a trade apprenticeship.

“I was struggling mentally and I had to put on a brave face. It was so tiring. I would just collapse after work – I was mentally exhausted but I had no choice – I had to support my family.”

Potter’s claim for permanent impairment, after fracturing his back during training shortly after returning from deployment, and claims for mental health injury, have been a five-year-process that ended two weeks ago. But he received a reduced amount because of various discrepancies, including date of discharge. He says an appeal was not an option – as it would have added 12 more months to his wait while caring for his wife, diagnosed with multiple sclerosis at the time, and his newborn son.

“It was the most distressing time in my life,” Potter says. “I went from being a performing soldier – I was proud to wear the uniform, stand with my brothers and strive to achieve. Slowly that was taken away from me, as with my mental health. I also was carrying physical injuries, which at the time was treated with prescription medication, which then was the start of the downward spiral.”

Both men say bureaucratic delays – including access to mental health experts – push already anxious and mentally vulnerable veterans to tipping point, and are a contributor to increased suicide risk.

“In that waiting period you have guys that can’t work, are suffering from PTSD, are in financial hardship – even with veteran support – and can’t access a psychiatrist,” Potter says. “Frustration with DVA delays and access to services pop up on the Overwatch pages all the time. The system is just not quick enough, so while veterans wait for their claims to be processed, they are without work, without real income, without support and without access to mental health services, and they start self-medicating with alcohol and prescription drugs, and things spiral out of control.”

The VMC Overwatch model is used Australia-wide and began with the Vietnam War vets but multiplied rapidly following the advent of social media.

Today, there are Overwatch pages run by various military units, like the Royal Australian Engineers Overwatch. To be accepted into these Overwatch pages you must have served in that unit, corps or branch. “That way it a safe place for each other,” Potter says.

There are also general overwatch Facebook pages, like national group Overwatch Australia, which in 2015 came to cover army, navy and air force personnel.

Overwatch Australia has more than 8500 volunteers and was initiated in 2013 by former and serving members of the Royal Australian Regiment following a two-week spate of suicides. Overwatch Australia monitors and responds to up to 10 or more requests a week filtered through social media, calls to the 1800 number and via the website contacts page. It can have a support network on the ground for a welfare check within 30 minutes.

“We are quietly and without fuss or funding providing a peer support service for veterans that we know helps saves lives,” Karen Court, from Overwatch Australia, says. “We focus only on suicide prevention and intervention, and don’t try to operate outside that scope. We prefer to establish working relationships with other like-minded agencies and refer to them for their specialities in whatever area of social, psychological or medical support the veteran might require.”

Adelaide mother and veterans mental health advocate Julie-Ann Finney says she is routinely contacted by family and friends of veterans who have taken their own lives.

Finney wants a Royal Commission into veteran suicide after her son David Finney, a Royal Australian Navy petty officer, took his life on February 1, 2019. David died 13 months after discharge and a long battle with PTSD. Three months before he died, he tried to make an appointment to see a psychologist but was told there was no DVA psychologists available until April.

Finney, 58, who’s attracted more than 365,000 signatures to a Royal Commission petition, said veteran suicide is happening across Australia every week. “I don’t know how they find me, but they do and there are many, many people suffering – just two weeks ago we had three suicides,” she says.

She is also contacted by veterans suffering alone, and conducts a weekly welfare check on at least one man interstate who is struggling to stay alive. “I keep reassuring him that we are going to get change – we are going to get a Royal Commission and it will shine a light into the darkness. And I tell him that he’s not alone,” she says.

The Morrison Government has rejected her calls for a Royal Commission. The ALP have promised to hold one if elected to government.

Instead, the Government last month announced an interim National Commissioner with ongoing powers to investigate, monitor and recommend change under proposed laws currently before parliament.

Finney is disputing the government’s appointment of Dr Bernadette Boss over conflict of interest claims. She says a Royal Commission is the only way for a transparent, independent and in-depth inquiry.

Veteran suicide is sadly not a new problem. University of Adelaide PhD student Jessie Lewcock is researching the number of South Australian World War I and World War II veterans who died by suicide. So far, she has waded through 18,000 police reports to the coroner, identifying more than 130 WWI veterans who took their own lives from 1915-1947.

She said one of the highest rates recorded was in 1937, when veterans made up about 5 per cent of the South Australian population, yet their suicide rate was almost four times higher at 23 per cent.

“An increased risk of suicide is unfortunately another, darker piece of the Anzac legacy that has been passed down from World War I,” she says. “It is definitely heartening to hear of Overwatch groups like this that are drawing upon the more positive qualities of mateship and bravery to reach out and help their mates while fighting and overcoming battles with their own mental health.”

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare says the official veteran suicide toll is 465 from 2001 to 2018. But a man who says he’s been to 60 veteran funerals in five years says that data fails to account for those veterans who were not DVA clients and were discharged before 2001.

Queensland Army veteran Scott Harris says 658 veterans have suicided since 2001, and the numbers increased by 140 per cent in the past decade.

Harris, who backs Finney’s call for a Royal Commission, has been compiling his own statistics on veteran suicides for the past five years for support group The Warriors Return. He says the only way to prevent veteran suicide is to understand its true cost and discuss it openly.

“I believe that we, as a nation, can move forward with this by talking about suicide as an illness – not as an easy way out, and bring it out in the mainstream and not hide from it,” he says.

Last month, the Federal Government announced a $101.7 million boost to mental health support for veterans, including the expansion of the Open Arms veterans and families support service, and expanded eligibility of the co-ordinated Veterans’ Care Program. There are currently more than 220,000 veterans in Australia and 100,000 dependants.

If you or someone you know needs help call: Open Arms on 1800 011 046 (openarms.gov.au); Overwatch Australia 1800 699 2824; Lifeline on 13 11 14 (lifeline.org.au); or Beyond Blue 1300 22 4636 (beyondblue.org.au).