Never surrender – Adelaide mum Julie-Ann Finney’s fight for a Royal Commission into military suicide after the death of her son

This day last year Julie-Ann Finney’s world came crashing down when she learned her soldier son had taken his own life. Since then, she has become the face of a national campaign for a Royal Commission into veteran suicide.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Adelaide mum calls for inquiry into military suicides

- Petition for Royal Commission gathers strength

- How to get the most out of your Advertiser digital subscription

It was the moment Julie-Ann Finney finally lost her cool – three months after she had buried her son David and a month into her public campaign calling for a Royal Commission into military suicides.

She was at work as a chartered accountant in Waymouth St in Adelaide’s city centre when overwhelmed with work and life issues the pressure valve burst.

“My brain was going ‘Just go home, Julie-Ann, you don’t have to put up with this’,” she says. “And then it was like you might see in a movie – or what people daydream about doing – but here I was actually doing it.

“I stood up, put my coat on and said. ‘Hey everyone, I’ve got an announcement to make’. They all turned around wide-eyed and I said ‘You can all get f*cked. The whole f*cking lot of you. I quit’.”

She walked out, burst into tears in the street and sobbed all the way home to Blair Athol on the bus.

It was May 16 last year and – having come to a mutual agreement with her employer to leave – she hasn’t worked since.

That is, if you don’t count a full-time job at the forefront of a growing campaign for a comprehensive judicial inquiry into the suicide crisis within the Australian Defence Force.

A year ago today, on February 1, 2019, her son, David Finney, a former navy mechanic, aged 38, took his own life.

Those stark details barely reveal the trauma his death triggered for his mother, father Grant, sister Jaimie and David’s child, Kate.

Their pain is echoed by thousands of bereaved family members of veterans across the country.

The rate of suicide among veterans is around 20 per cent higher than for the general population. There were 42 confirmed suicides of ADF current and former personnel in 2019, but suicide as a cause of death is hidden and under-reported for different reasons. Julie-Ann believes more than one death a week on average is the true figure.

“The official figures don’t include single-person accidents, and where the family isn’t prepared to acknowledge suicide,” she says.

“For many, suicide is still shameful and for Christians it’s a sin. I couldn’t say the word myself for the first six months.”

I first met Julie-Ann on a cool morning in April last year for an interview that would feature on the Anzac Day front cover of The Advertiser. For the entire hour we spoke she trembled, more from grief than the cold. She was birdlike, painfully thin and hunched over as if she was holding something she never wanted to let go. But she was single-minded and determined like no one else I have met.

“I am the mother of David Stafford Finney and I will protect his name and legacy with all I have from now until forever,” she told me.

She has been as good as her word.

That day Julie-Ann said a Royal Commission was her mission.

Only an inquiry of that magnitude would honour the struggle of David, who campaigned himself for a better outcome for veterans with mental health issues.

It might have seemed far-fetched, an unachievable goal for a grandmother from Adelaide’s inner-northern suburbs, with no public profile and no political experience – but I told her I believed she could make it happen.

Since that day Julie-Ann has been on an epic rollercoaster.

She has spoken with every major political figure in the country and all the military top brass. She has begun a petition on change.org that has seen almost 300,000 people in just nine months sign the online protest call. She has been featured on every national news channel and in every newspaper. But she is yet to achieve her goal.

There have been promises and platitudes, support and staunch opposition, and abuse of the most vile kind.

Sometimes the cruel words are delivered by people she believed to be on her side.

“I might appear strong – but often I cry myself to sleep. It does affect me,” she says. “I don’t fight people when they attack me because this is not about me.”

She has shared the pain of loss of a loved one with dozens of veterans’ families and received harrowing final calls and texts from veterans claiming they are about to take their own lives.

“If I know where they are I ring triple-0 and, if not, I do my best to find them or alert a loved one,” she says. “I’m not trained to do anything – I just do the best I can. It’s horrific and heartbreaking. I don’t allow myself to get angry, because that will just distract from the need to continue on for a Royal Commission.”

As her campaign built throughout the middle of 2019 there were encouraging signs the Federal Government was edging closer to a full commitment, but since then her optimism has fallen.

It was at a private meeting, the day after Remembrance Day, in November, she finally realised she was having her “tummy rubbed”. It didn’t feel good. The only other two people in the room in Canberra were Defence Minister Linda Reynolds and the Chief of the Defence Force, Angus Campbell.

“The only talk about veterans in that meeting came out of my mouth,” Julie-Ann says. “They asked: ‘But what can we do for the mothers? Can we strike a medallion – or have a special day. Maybe set up a forum?’

“No matter how often I rejected their ideas for ‘the mothers’, they kept on at me. Their agenda was clear. No wonder they wanted to keep that meeting secret but I want it on the record now.”

Eventually she looked them in the eye.

“What you can do for the mothers is give us back our children,” she said. “You can give me back my son and fix my daughter – that’s what you can do for me.

“I want my child, I don’t want to be here arguing with you. If you’re not going to give me my child back then give me a Royal Commission. We don’t need any more grieving mothers added to this story. Just get it done.”

It is hard to believe this is a woman who left school at 15, had two children by 17, was divorced and alone at 20, had a fear of addressing a room of friends – never mind those in authority – and has never held a public role.

David’s death and her decision to honour his name has led to an extraordinary 12 months – all the time trying to keep her self-control, including not permitting herself to truly grieve. The nadir was New Year’s Day.

“I couldn’t hold it together because from then on I had to say my son died last year,” she says with the emotion flowing.

“Every day is a day further day away from David. And that’s not fair. It scares me that when I do break, people will think I should be over his death but I haven’t even begun to deal with it. I don’t want to be all alone when I break – I’m scared.”

She has been out to her son’s grave at Golden Grove with the media, but never alone. “I cannot go to his graveside until I can bring the news to David that he did it,” she says. “He got what he wanted, which was help for all veterans. I can’t stop until that happens.”

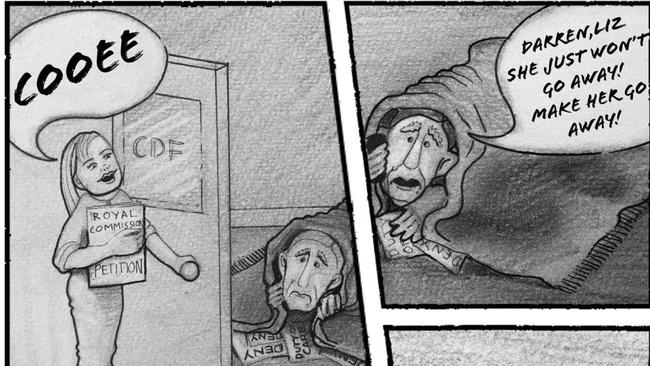

The federal politician she has clashed with most is the Veterans’ Affairs Minister, Darren Chester, who has mentioned David by name in interviews. He has suggested the young man diagnosed with post-traumatic stress, who was discharged from the military while lying in a hospital bed after a suicide attempt, received the best care possible during and after his career.

“He (Chester) told me he’d spoken with other family members who have given permission for him to talk about David, but I can’t find one,” Julie-Ann says.

She got so upset she walked into Parliament House one day demanding to see him. Security was taken aback.

“I told them that Minister Chester had told me his door was always open and this was the moment he could prove it,” she says.

And the minister did. He was meeting with Veterans’ Affairs Department top staff and he permitted Julie-Ann to address them.

“I told them this was not about DVA, it was all about veteran suicide,” she says. “It starts from recruitment through training and deployment and finishes with end of life. Over more than 100 years that’s the journey we have never adequately investigated and understood. I felt they listened respectfully and were empathetic. I walked out – and nothing has happened.”

She was less impressed with Chester’s openness when sitting patiently in his ministerial office waiting to discuss the next step on the road to a top-level inquiry. She looked up to see him being interviewed live on Sky News on the parliamentary lawns and effectively saying that he didn’t support a Royal Commission.

Political shenanigans are maddening for the woman who was “a confirmed swing-voter” without “a political bone in my body” a year ago.

“I’m forever being told that my campaign manager is very well known in political circles,” she says. “Well, I’m waiting for them to tell me who my campaign manager is.”

It could well be her mother, Jan Harnas – at least, she’s her biggest fan.

Julie-Ann brought her mother to The Advertiser Women of the Year awards night in December, where she was “genuinely shocked and humbled” to win the major award in a room full of remarkable women.

“I brought her along thinking it was a bit of glamour as a Christmas Party cocktail night, never expecting I would win,” she says. “Mum was incredibly proud and wanted to tell everyone she knows. Dad (Bob Harnas) was thrilled too of course. He’s pretty keen to meet the Prime Minister one day.”

It was December, 1961 when Jan gave birth to the second of her four children and only daughter, Julie-Ann, at McBride’s Maternity Hospital at Medindie.

Her parents divorced when she was 10 and she confesses she went off the rails as a hippy and rebellious teenager soon afterwards. She met Grant Finney, a couple of years older, at a party, and left Thorndon High School at Paradise at the age of 15, heavily pregnant. Daughter Jaimie-Lee was born in 1977.

Grant and Julie-Ann married two years later when she was 17, and again pregnant.

David was born at Queen Victoria Hospital in Rose Park on February 17, 1980.

The family moved to Salisbury North, where Grant joined the air force, and then to Richmond in NSW during his extended training.

Two years later, just out of her teens, she was divorced with two young children and back in Adelaide living at Hope Valley.

“I loved being a mum but there were times I felt sorry for my children,” she says. “I worked two jobs, in a deli in the day and a chicken shop at night. There was no time for another relationship.”

She went back to school to earn a commercial certificate, then completed a bookkeeping course, a diploma in accountancy and finally a bachelor degree and postgraduate studies. By 1997 she had saved sufficient to build a small house at Hillcrest.

Jaimie left home the same year and got married, and David left soon afterwards to join the navy. She found herself alone for the first time in life, working to advance her career, and longing for grandchildren.

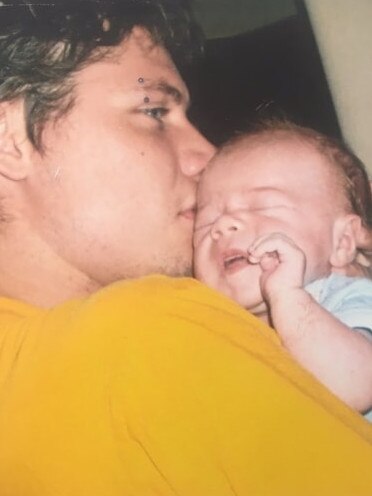

David’s son, Kayne, was born in Sydney in 2007.

“I remember feeling so lucky this perfect little baby was born,” she says.

“I put him in my arms and I was thinking what name could I be for him, I wanted something a bit different. But as I looked in his eyes I told him, ‘Look, for you I am happy to be grandma’.

“I got over to see him and bath him and be with him – and then Kayne died.”

David, who had won a naval commendation for his bravery fighting a fire on HMAS Tobruk in 2004, traced the beginning of his mental decline to his son’s death at just seven weeks from sudden infant death syndrome.

The heartbreak came on top of the trauma of his work in the navy, which also involved rescuing refugees and recovering bodies, including children, from the ocean.

“Hearing their stories, seeing sick kids only a couple of years after I lost my son as well – all those things intertwined in my head and I couldn’t feel safe for anyone around me,” he said in an interview in 2018.

Before they divorced, David and his wife had a second child, Kate, born just 11 months after Kayne’s death.

Julie-Ann is estranged from her former daughter-in-law, who lives interstate, and hasn’t seen granddaughter Kate of late.

“I trust and know that her mother is looking after her and doing her very best,” she says. “I’m hoping to re-join with Kate, who was the love od David’s life, one day and I’m lucky to have three grandchildren (Jaimie’s children) close by in Adelaide. I always say I have two children and five grandchildren and that’s the way I regard it. I won’t put it any other way.”

Her three brothers have been solid support and she’s found solace and adventure with another band of brothers and sisters.

Soon after the Anzac Day article she received a message. “I don’t answer messages from strange men,” she says.

“Then, when I was on A Current Affair this guy sent another message and then another.

“I was thinking he was a bit of a stalker but, and I can’t really remember why, I rang him one day. I just felt I should. We talked for an hour – well, he did, as I didn’t get more than a word in.”

George Koulakis, an RAAF veteran from Queensland, was the man who had left an impression and gained her trust.

In 2014 he formed the Cameleers for retired ADF veterans looking for new challenges to help them adjust to non-military life.

“George told me as a veteran David was his brother,” she says. “So that made me a mother for all veterans. It was very powerful.”

Last September the Cameleers left Adelaide for a trip across the Nullarbor Plain with a new recruit. The deal was sealed when they promised her a caravan to sleep in – not just a tent.

At Ceduna she felt the sadness that can hit any time and wandered off only to find herself on a dirt road, with no phone and the sun going down. Just then a drone buzzed overhead.

“They were worried and out looking for me the way they knew best,” she says.

“They had a Kangaroo Court and charged and convicted me with going AWOL (absent without leave).” The sentence was severe: three days driving across the Nullarbor with George, and no earplugs.

On another trip to the Birdsville Track, she hiked miles, jumped into a muddy pool over her head, abseiled down rock walls and drove a 4WD to the top of a giant sandhill. It was adventure and comradeship like she’d never known

“They joked I’d started off as a princess in a caravan and finished off as Queen of the Desert sleeping under the stars,” she says.

It was in the middle of nowhere on the Birdsville Track that she had her first emotional re-encounter with David. Seeing a large pile of rocks at the top of a sandhill, she had an urge to climb. “I put a large rock on top for David and placed a smaller one at the bottom for Kayne. That way, David was looking over his son.”

Then, she stood back from the cairn and looked out across the vast expanse of nothingness. “I wanted to scream, I wanted to be hysterical, stamp my feet and be a small child once more,” she says. “All of a sudden I knew I needed to be at that place alone.”

One of the veterans, also called David, saw her tears for her son. He took a pin from his wallet he said had kept him safe during his time in Afghanistan 20 years ago and placed it inside the rock pile.

“It was such an important gesture,” she says.

“When I told him I was not OK – he knew what that meant and knew what to do. This was the first time I didn’t have to look after anyone else – not even myself. Those guys looked after me.”

The Cameleers have agreed to take her back to the same site, and drive away.

“I need to be there alone for as long as it takes – and that may mean days,” she says.

“We’ll have protocols where I have a two-day radio and report in every few hours.

“Out there is not where I think my son is but it’s a place I felt close to him in a way I couldn’t and haven’t previously. And it’s where I don’t need to be this person that I have to be for now, for me, for David and for others.”

She has seen a lot of George in the past six months. as he has videoed her at high-level Canberra meetings and the Save Our Heroes Summit in the NSW Parliament House.

Politicians who have been supportive include SA Senator Rex Patrick, Tasmania Senator Jacqui Lambie and NSW Senator Jim Molan, all military veterans.

But she gives her greatest praise to Federal Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese. She met with ‘Albo’ and two Labor lieutenants, Richard Marles and Shayne Neumann, at Parliament House in November.

“Albanese told me he had never walked out of a meeting where everyone was so on the same page,” she says.

“He walked into parliament that day and said Labor would back a Royal Commission every step of the way.

Scott Morrison responded that there had been many changes in the ADF and DVA and stated, referring to me, ‘I wish that those arrangements had been in place when her son died’.

“Well, they are in place now and we had six known veteran suicides over the Christmas break. Their (ADF and DVA) wonderful changes didn’t help them.

“What I want to know is, in what world do we allow more than one a week of our bravest to die and have no investigation? The Prime Minister told me money was not a problem with calling a Royal Commission, so I ask him – what is the problem?”

David Finney’s 40th birthday would have been on February 17 this year. His closest family will celebrate and commemorate in private. Julie-Ann will hold a public ceremony in his memory in Canberra on February 22. The event is ticketed. Proceeds will go to David’s favourite charities: Camp Quality – where he was a volunteer – and Menslink, where he worked as a mentor to young men.

Julie-Ann’s pledge to her son remains. “This government wants me to have buried my son and to have moved on,” she says.

“But I promised him in my eulogy as I promise him now, David’s story is not over. He didn’t die for nothing. He can’t have. I just won’t allow it.”