Why the local butcher’s shop is now a threatened species in SA

Nothing was pre-cut, de-boned or pre-packaged in plastic. And there was always a generous free slice of fritz! Bob Byrne laments the slow demise of the old-school butcher shop.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

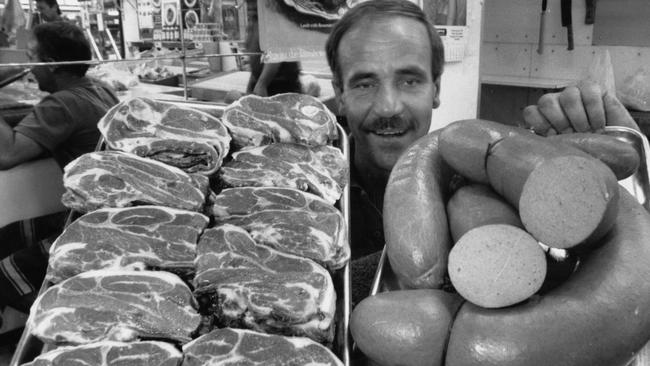

A free slice of bung fritz, the smell of sawdust on the floor, the sound of a high-speed electric saw cutting through bone, sides of lamb and beef hanging at ceiling height on huge hooks – all memories of the old butcher shop.

Various-sized saws and hacksaws, along with a mixture of cleavers and machetes, dangled about shoulder height, a huge wooden chopping block stood like an island behind the counter which was always neatly set out with its fresh stack of white butcher’s paper next to the weighing scales.

Also behind the counter was the butcher, in a dark blue and white-striped apron, trusty scabbard at his side with various-sized knives and an oft-used sharpening tool.

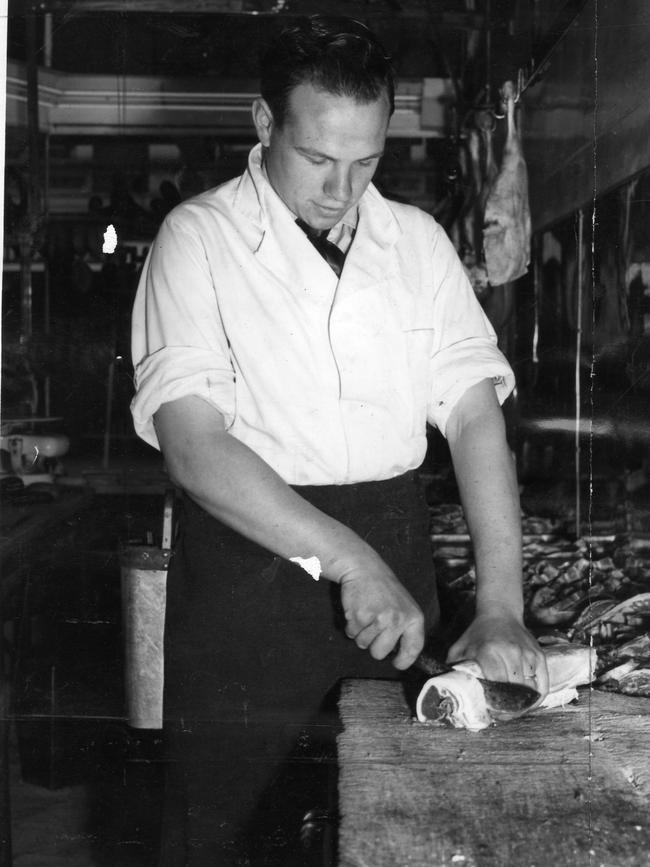

They were almost always big men. It was (and still is) a demanding job and heavy work, carrying around and carving up meat carcasses that might weigh up to several hundred kilos. Those butcher shops I remember from my childhood years bear little resemblance to the sterilised experience of the meat section of our modern supermarkets.

Gone are the whole or half carcasses and prime cuts of the animal. All the breaking down and carving up takes place behind the scenes and we are presented with a neat plastic-wrapped package of the various cuts.

Although you can still find a few old-school butcher shops around, they are getting thin on the ground. Last century they were spread abundantly around the city and suburbs.

Along with the local deli, newsagent, greengrocer, and hardware store, they usually stood in a strip of shops.

Almost all are gone now, replaced by large suburban shopping malls, and a giant hardware chain.

Butchers always seemed to run in families, the craft handed down from one generation to the next in an unbroken line.

Many could trace their butchering history back a century or more to grandparents and even great-grandparents.

And you always knew the real butcher, he was usually missing a half a finger.

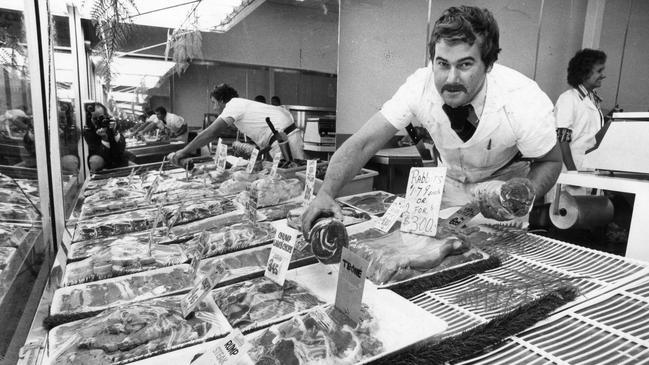

Nothing was pre-cut or de-boned. Nothing was pre-packaged in plastic.

Everything was fresh – lamb chops, steaks, mince, kidneys, brains, tongue, liver, all weighed separately, wrapped in butcher’s paper and the pencil from behind the ear recorded the price of each packaged item.

Sausages and bung fritz were made on the premises and people were known to travel miles and across suburbs for the more famous smallgoods.

The lamb roast, most always cooked for Sunday lunch, was constantly in high demand.

The local butcher and his family were part of their community, went to church on Sunday, knew all the customers by name and also knew which cuts they preferred.

Butchers actually butchered back then. The whole animal, skinned and gutted at the abattoir was delivered into the cold room and hung from a huge rack.

The butcher had to know how long to “hang” the meat to increase the flavour: “The longer meat is hung the better the taste, but also a greater chance that it will spoil,” an old butcher told me, adding: “It’s a bit of an art.”

The style of meat in butcher shops has changed over the years.

When times were leaner and families lived on a single income, usually with extra mouths to feed, cheaper cuts were popular. Mutton and hogget were more affordable, steak was rarely served up at home and chicken was only ever seen at Christmas.

Offal was more acceptable too and the cookbooks from that era carried recipes for lamb brains, chicken livers, tongue and even tripe.

Incidentally, my mother loved tripe, but she never forced it on the kids. Every now and again she would buy a generous serve of tripe from our butcher and cook it with milk and onions just for herself, while we’d tuck into a meal of hogget chops, mashed potato, pumpkin, and peas.

Long before the days of the “value added” tag, butchers knew how to attract and keep new customers. There was always an extra sausage or two thrown in and every kid got a generous slice of fritz.

Scraps of meat, offcuts and the ends were put through the mincer and sold cheaply (or sometimes given away) as pet food. There was liver and lamb shanks for the dog, chicken necks, organ meat with ground bones for the cat.

The neighbourhood butcher was like the local bank manager (remember those?).

There was a certain amount of trust, and you could always buy with confidence because he needed you as a long-term customer.

The advice and suggestions on preparing and cooking were given freely, and he most always had ideas on cuts you’d never considered before.

But as many small independent businesses begin to feel the current squeeze of rising wholesale prices and supply shortages, it’s likely that more will finally succumb to the inevitable and disappear.

The old-style butcher shop, so much a part of every Boomer’s childhood, is now a threatened species.

Bob’s latest book Adelaide Remember When: The Boomer Stories is out now. He posts memories of Adelaide every day on Facebook.com/adelaiderememberwhen/