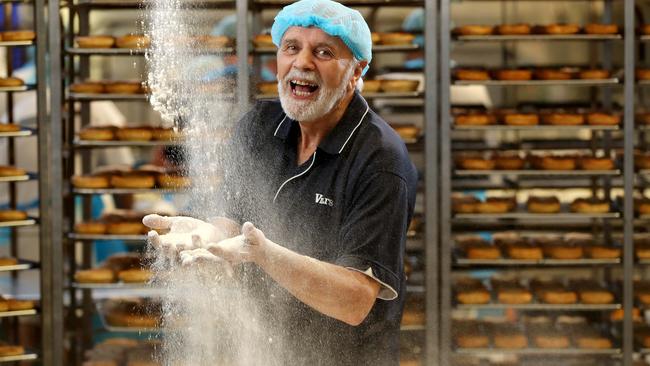

Vili’s pies: Adelaide pie maker Vilmos Milisits celebrates 50 years as baker and reveals future for his SA empire

In 2018, Craig Cook sat down with Vili Milisits to talk about his humble beginnings as a Hungarian refugee and how he built one of SA's most beloved and iconic food brands, Vili's Bakery.

delicious SA

Don't miss out on the headlines from delicious SA. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Pie cart back makes triumphant return to Adelaide for Crows match

- South Australian pie king’s Cafe De Vili’s opens north of Adelaide

- South Australia’s 50 most influential people of food and wine

- Adelaide’s top 25 pies from the city to the sea

This article was first published in 2018 in Vilis' 50th anniversary year and traces his refugee roots and his rise to become one of South Australia's most respected and successful businessmen. Milisits died in Sydney overnight after an unsuccessful operation.

Vilmos Milisits remembers with chilling clarity the moment his childhood came to a brutal end. It was 1956 when a young boy faced a horrifying choice – leave his beloved, howling dog at home in Hungary, or let it be shot by guards when his fleeing family reached the border with Austria.

The boy, who as a man became ‘Vili’ – a giant of the Australian baking industry – was nine years old and the youngest of a politically active family of eight escaping the upheaval of the Magyar uprising against Soviet occupation. It is a moment burned forever into his memory.

“That dog is still the greatest loss of my life,” he says. “He went everywhere with me for five years. Followed me through the forests in snow and heat, every day, never leaving my side.”

A dog, a german shepherd, was never named, but as Vili tells his story it is clear that incident changed his view of life forever.

“My dad told me they would shoot him at the border so we had to leave him behind,” he says. “I tied him to a fence, my constant companion, on a long chain and kept walking. All I could hear was him howling. And I howled, too. I’ve never forgotten that howling.”

Remarkably, he’s never been back to Hungary and probably never will.

The dramatic border exit, an exodus taken by more than 200,000 Hungarians during the uprising, was the beginning of 18 months being shunted from one miserable makeshift refugee camp to another. There were camps across Austria and Germany, and finally on to England and Wapping in central London.

The man who now bakes more than 40 million products a year to feed hungry mouths in 18 countries, knows the gut rumbling empty horror of true hunger. With no money and often only a slice of bread and cup of cocoa for dinner at the internment camp, Vili and his brother Steve would jump the fence to roam the streets.

When the local chip shop opened at 6 o’clock the Milisits’ brothers would have their noses pressed to the window. “Not for the fish but the burgers and chips… they drove me mad,” he says. “I decided there and then I’d never go hungry ever again as soon as I had control in my life. I’ve seen people happy in poverty but never in hunger. It destroys you. People kill when they’re hungry.”

We’re sitting in his cafe just a few steps away from where Vili’s bakery in Mile End began 50 years ago this year.

The 69-year-old heads to his office at least five times a week and has his lunch out in the cafe with his customers. One man approaches to praise the pie floater he’s just devoured: “The best I’ve had,” he says.

Not every customer is happy, but he listens intently to the commentary, good and bad.

“The worst thing you can do is to buy a business you know nothing about – because your staff won’t tell you the truth,” he explains. “But your customers will. I listen and I learn from them.

“I serve meals on Saturday and the staff call me ‘Mr Chip’. Chips need heat. I learned that in my first job in Australia in a fish and chip shop aged 12, slicing potatoes for hours at a time with a one armed bandit. There’s an art to every job you do.”

The name of his famous global baking empire is also his nickname, Vili. He began the business half a century ago with wife Rosemary, from the tiny kitchen table of their rundown cottage. But there was a time he was too embarrassed to have his name on his pies, pasties and sausage rolls. He was ashamed of making “peasant food”, a betrayal of his true trade.

“I was taught the old way by masters to pull and stretch and tease sugar into shape… I can make roses from candy fit for royalty” he says making figures in the air with his hands.

“I was trained to be an artisan confectioner; an artist in sugar. My mentor (Kazzy Ujvari) told me making pies and pasties was belittling, below me. And that’s how I felt when I began. I felt shameful and desperately didn’t want my name on them.”

Advertising guru, Andrew Killey, who had just founded KWP! with Peter Withy in the early nineties, changed his mind, convincing him to spend a fortune promoting himself.

“Andrew told me: ‘You make the best product I know Vili – why don’t you tell the whole bloody world’,” he says with a characteristic toothy cackle. “I reckon I’ve spent $5 million telling the world since then. Advertisers love spending your money.”

Along with Rosemary they devised the concept of the big blue V on the pavement – visible from 100m away. The couple instigated a new Adelaide industry, building A-frames to hang the signs from and had 800 made in the first year.

Two other initiatives completed the branding transformation. They threw away $300,000 worth of baking trays, replacing them with ones embossed with a V on the bottom. Turn up any pie and only the big V authenticates it as a Vili’s.

“If it hasn’t got a V – it ain’t me,” ran the commercial radio slogan. He’s made more than 100 commercials over the journey. All but the first one – where he reckons he sounds like a cheesy DJ – were recorded in the grand lounge room of his Unley mansion, Northgate House.

The strange chiming sounds in the background weren’t added sound effects but the striking of the numerous antique clocks Rosemary loves and collects.

Vili appreciates his trappings of wealth in a country he loves with a passion.

“I’m Aussie… I’m more Aussie than some people born here and that’s because I appreciate this country more,” he says. “Our climate, our food and our wine are the best in the world. This country is magnificent. I know because I’ve been in places far worse.”

The rat-infested London internment camp on the north bank of the Thames just down from Tower Bridge was one such place. The area was still bombed out from the incessant Luftwaffe raids of 15 years previously.

“Europe was being rebuilt and yet England, who won the war, was still a demolition site, gripped with poverty and deprivation,” he says. “It still is in parts. I’ve got a photo of one of my vans crossing Tower Bridge and there in the background is a fence, half fallen over, weeds growing all over, that I swear was there 60 years before.”

He’s been back to walk those streets and was stopped in his tracks looking at the Captain Kidd pub, named after the 17th century pirate William Kidd, who was executed at the nearby Execution Dock.

The pub has an imposing brick wall that runs along the river.

“You’d be walking by and there would be a kid pop out at one end and his mate would be standing at the other,” Vili recalls. “They’d greet me with ‘hey… how you going you bloody wog?’ – then they’d give me a bloody good beating. We were the first refugees after the war and we weren’t very welcome. We spoke a strange language and had different food.”

Being called ‘wog’ remained commonplace when he arrived in Australia.

The Milisits family was keenest to be accepted into America where they had relatives but the wait was three years. The queue for Australia was only 18 months.

Leaving Trieste, Italy, by ship, travelling five weeks steerage class, they arrived in Melbourne and caught the overnight train to South Australia the same day.

“We were from central Europe, lush and green, and all we saw was desert, dry, kangaroos and rabbits,” he says. “My mother cried, ‘Where are we going to end up?’”

Carrington St in inner city Adelaide was the answer. But soon after they set up house Vili’s father, who had been persecuted and tortured by the Russians, became ill. He died the next year.

Despite enjoying the intellectual challenge of school, Vili, then 14, had to find a proper job. He followed the profession of his parents, both chefs, who he says were “born to good food and good living”.

His parents met in Vienna in the 1930s and returned to Hungary before World War II to buy a small property to raise their growing family, farming sugar-beet, corn and wheat. When Russian Communism arrived they had to hand over 80 per cent of all produce to the state and the family existed at a subsistence level.

The property had a giant in-built oven in the centre of the farmhouse, primarily for bread making. As the youngest, Vili would have to climb in and sweep out the ashes. Dreading he’d be locked in, he had nightmares of the Hansel and Gretel fairytale. Those imaginings returned when he secured his first job as an apprenticeship at Kazzy’s Cake shop, first in Rundle St, Kent Town (a car park now) and later at Burnside.

Kazzy was a man with “gifted hands and quick feet” who could plant one on his rear end. “He could be harsh as a disciplinarian – but it probably did me good,” Vili says.

“If we have an issue with an apprentice today you can’t give them a gee-up in case they get ‘offended’. We’ve got to put his mittens on, give him a cuddle, wipe his nose and change his nappy and I have the ultimate privilege of paying him as well! It’s such a different world.”

Staffing, he says, is a constant headache. He employs more than 300 including 260 at his SA plant and cafe. “It’s hard to get good staff because many people don’t want to work at all,” he says.

“More than 5 per cent of our staff are special needs. Lovely people… and they roll up every day. They never have a sickie. Having a job is heaven-sent for them. Some people take jobs for granted.”

Like many self-made people, Milisits speaks his mind. Relatively unrestrained by political correctness, he is unaware – or doesn’t care – that some of his attitudes and speech might offend. He has been accused, including by former staff, of uttering derogatory, homophobic, racist and misogynistic remarks.

“My three in-house accountants are female; my kitchen manager and cafe manager all females. My PA was female and, at a time, my production manager was a woman,” he says, defending himself against the misogyny claim.

“I reckon women are the best at certain jobs… especially in counting… they are more meticulous than any man I’ve ever known.”

He met Rosemary, a former nurse, at a 16th birthday top heavy with girls. He was a late call up, along with a few mates, to grab a dance partner.

“There were five of us – all wog boys – a Pole, a Greek, Croatian, Serbian and Hungarian – it was the United Nations!” he says relishing reliving every moment.

“Rosemary’s family – the Bonners – were Catholics who came out on the second ship into South Australia. We couldn’t have been more different.

“It was a West Side Story job. She was the first Anglo-Saxon in my family… and I was the first non-Anglo Saxon. Neither side was happy. Neither wanted either. We almost eloped it was so stressful.”

They were married four years later at the SA Country Women’s Association on Dequetteville Tce. Vili was up at 4am to bake and then deliver their wedding cake to the venue. Two hours later, in his best suit, he returned as groom.

There was a smattering of Milisits family members and 300 Bonners at the reception.

“I turned to my father-in-law, Frank, and told him he was lucky I’d come along,” Vili says. “He looked a bit unsure, so I said… ‘Have a look at your mob, they’re all knock-kneed and sticky out ears. There’s way too much inbreeding.’ Frank laughed loud. We got on okay.”

He’s proud there are three generations in the business, with children Simon and Alison, and two grandsons, Simon’s children Josh, 25, and Luke, 21.

The day he finished his apprenticeship and walked out of Kazzy’s he told himself he’d never work for a boss again. He hasn’t, other than doing household chores for Rosemary.

It began with just $50 from the sale of his “pride and joy”, a hotted up Austin A40. Next, just married, but without his wife’s permission, he bought a cottage at 14 Manchester St, Mile End, and built a bakery out the back. “I thought it would last me a lifetime,” he adds.

In a way it has, although as the business has grown he has bought out much of the surrounding suburb.

For 10 years, working 90-hour weeks, the bakery produced continental cakes, employing 17 people at its peak. But by the mid-70s the immigration ratio had changed with more people coming from Asia than Europe. Realising keeping still in business means financial ruin, the couple took the radical and brave step to change to savoury.

“My wife made the first pasty chopping up the vegetables with a machete on the kitchen table,” he recalls. “The Asians didn’t like the short crust pastry… too stodgy… they like the flaky pastry that the French used. Our pasties where a complete meal, meat and six veg – swedes, turnips, trombone (marrow), onion, carrot and potatoes.

“And we made them hot – adults only with chilli and black pepper to burn your lips. The average Aussie couldn’t handle them.”

His sister owned her own patisserie, Olga’s Cakes in Leigh St in the city, and the pasties were first sold there. When Sturt St grocery store owner Con Bambacas saw some pallets in the back of a van he wanted the product.

“Con was my first big pasty customer. Within weeks we went from making 500 a day to 5000 a day but I still told them call them homemade, nothing else. Soon they were in every corner store.

“Australia was built on the corner store. They built my business.”

The 2000 Sydney Olympics put Vili’s on the national map. They made and sold 1.4 million pies in 16 days on top of normal production. His current operation is built with the next 25 years in mind. Operating 20 hours a day, six days a week – industrial crews come in to clean half day every week – the Adelaide bakery pumps out 12,000 pies an hour but could double that if necessary.

Diversifying and investing in real estate was not just a strategy to expand the business. He owns 14 blocks on Manchester St and is always on the lookout for more.

“Some people are still holding out but I’m going to live forever so I can wait,” he adds. “One guy’s 96 years old and he won’t sell but I suggested that his son might!”

He’s had offers, big offers, to sell his business – including one from South African interests 15 years ago for around $35m – but he’s not holding out for more.

“And I’ve had far higher offers since,” he adds. “I’ve been offered more money than I ever thought I’d see – and I turned it down.”

One buyout offer was from a South Australian company. I ask if the company name begins with “B”? He laughs hysterically but can’t say.

“I said it’s not for sale and they said ‘Everything is for sale’ and I had to agree with that,” he says.

“I said go back, double your offer and I’ll consider it. It was a lot of money, but I’ve built a business for my children and all future generations, if they are willing to work. Nothing comes for free in life.”

He reflects on the early days, taking on the entrenched icon of Balfours.

“The greatest asset in business is to be underestimated by the opposition,” he says leaning forward. “My rivals stuck with tradition. Their advertising said: ‘Like a pie should taste’ what’s that about? Things change, and tradition is really about what someone else likes.

“They underestimated that half the population are born overseas – or their parents were.

“They put mutton in their pies. For people from Eastern Europe mutton is offensive. You want to make an enemy for life, feed them mutton. It’s cultural in the mind, and in the nose. Mutton smells, it lingers.

“I brought in choice – steak and mushroom, chicken rendang, satay, curry, goulash, green Thai.

“By the time they woke up I’d got 20 per cent of their business. They spent $1 million buying 10 per cent back so I got 10 per cent for free. And they called me an idiot!”

Only an idiot like Vili would open a 24/7 cafe in an industrial area of Adelaide but today it has iconic status. People come direct from the airport for a feed and anywhere the truckies stop again and again must be doing something right. With an alcohol licence – and the pie floater high on the menu – there’s nothing in Adelaide quite like it.

He built the cafe as a “guinea pig” to trial new products, but it’s now a highly profitable business. Vili’s cafe Mark II, on Main North Rd, Blair Athol, is equally successful.

“You’ve got to understand the markets,” he says. “That’s where the profit lies. You have to know what your ingredients cost. The margins count. Small things become big. Half a per cent on millions is a lot of money.”

He has come to understand large regional differences in Australia: For example he cannot sell a pasty in NSW, it’s exclusively sausage rolls and pies. Queensland is the biggest pie market in the country but he is yet to really break in. His biggest commercial failure happened in the Sunshine state with the launch of a cold turkey pie. “I still believe one day it will be a big seller, especially up north,” he says refusing to be beaten. “For the cafe market not the deli market. A lean meat pie with thin pastry that can be eaten cold with a side salad. It can work.”

Beef pies are still the biggest seller but the green peppercorn is Vili’s favourite. He will have gluten free pies soon, made off site to ensure they remain uncontaminated with wheat flour, and will bring back an old favourite, the chilli pie, with the notorious advertising tag: “This one will burn at both ends!”

The US and China have been difficult markets to crack. “We learned pretty quick who runs America – it’s the transport workers, the unions, the police and the fire brigade,” he says raising his eyebrows.

“Greasing palms and feeding everyone along the way is how you get things done. Two entire pallets of pies disappeared from one shipment and their highly intricate tracking system never found them. Then customs were supposed to take away some pies to test the products. We had six different products but they took 15 boxes of Steak and Mushroom – 36 in a box, 500 units! I knew I was being taken for a ride.

“We won’t call it corruption, more self-service. Just help yourself! They call it the land of the free, but I was paying for everything.”

China remains the jewel in the crown. He’s been in Hong Kong for 20 years but he wants to enter the mainland on his terms.

“The Australian government is so weak,” he claims. “The Chinese can come in here and buy up our farms but we can’t invest in their country. I can’t buy a brick in China – but they can come and buy me.

“I walked away from China 15 years ago and not much has changed. I believe they would pick my brains and then kick me out.”

At home, he’s had tough negotiations with well-known Australian supermarkets.

“They don’t want to pay so I don’t deliver,” he says with a smile. “One of them asked, ‘Who do you think you are?’ I told them I’m a guy without a mortgage.”

Another lengthy battle was with the South Australian health department over a 2012 claim his products were the source of a salmonella outbreak that affected 100 people. Milisits sued for defamation in a case lasting six years and costing more than $1m in legal fees.

“They named me when they shouldn’t have. I won but we’re still arguing over legal costs,” he says. “I’m privileged – I can afford my justice, which is such an indictment on the legal system.

“Small business can’t take on the government but they picked the wrong bloke when they picked on me. When I’m right I fight. When I’m wrong it’s damage control – pay up, shut up and get the hell out of there. We all make mistakes.”

Four times he’s risked a lot in life – mainly expanding the business – but he’s never risked his marriage.

“We are married 50 years this year but I’m a very tolerant man…,” he says, laughing uncontrollably. “We are culturally very different with our own opinions but that’s why it works. I tell her she’s a lucky woman – but I always do it with a smile.”

He is rightly proud of their OAMs, awarded on the same day in 2005, primarily for significant charitable contributions to more than 50 organisations, including Mary Potter Hospice.

Forever the crazy marketers, for holidays the couple drive around Australia dropping in on retail customers from Broome to Bateman’s Bay and Devonport to Darwin.

“We want to see Australia and this is a great way to do it,” he says. “I walk in with a shirt, mug and cap and often I have to show my driver’s licence to prove I’m Vili,”

Their biggest adventure was out to their most remote customer, at Hermannsburg, an aboriginal settlement, 125km southwest of Alice Springs.

Vili pulled up to the general store and one petrol pump, at the end of 60km of dirt road, in his brand new Mercedes 500.

“The guy was open mouthed but we sat down and had a beer. ‘We don’t see reps out here, never mind the owners!’ he said. Reckoned I had him for life.”

Baking has Vili for life, too. He says he’ll “never retire” and is “far too young to write a book”. “There’s this ongoing conflict between my brain and body,” he adds. “My body thinks it’s 69 and the brain says 49 – so we settle for 59.”

The immediate future holds a long convalescence from the aftermath of another hip operation, complicated by a strangulated hernia that prolonged recovery.

He spent six weeks away from the business in 2014 with a first hip operation after leaping for his life from the path of a speeding car – and hitting the bitumen hard – just outside his cafe.

The driver was convicted of driving in a reckless and dangerous manner, and ordered to serve a 12-month good behaviour bond. He also paid the injured baker $1000 compensation. “I got a better deal than him,” he says ruefully.

He has to take life a little easier since the incident and indulge other passions, including a good red (the 1999 Elderton Command Shiraz from the Barossa is his favourite), and deep sea fishing trips in Spencer Gulf on his luxury boat.

There’ll be another pie out soon – “with added zing” – that remains top secret for now. And he will likely make his first radio commercial in 10 years; as well as air some of the classics from the ’80s when he was the “wog pieman” with the funny accent trying to teach Aussies how to bake a national institution.

“Rosemary and I wake at 4.30am every day and we roll out of bed with laughter thinking of all the bullshit that’s happened in our life,” Vili adds. “But we know we’ve got a lot to be thankful for – life in Australian is good, very good and when something is this good, you stick with it.”