China-Australia trade: Wine, wool horticulture watch warily as trade spat continues

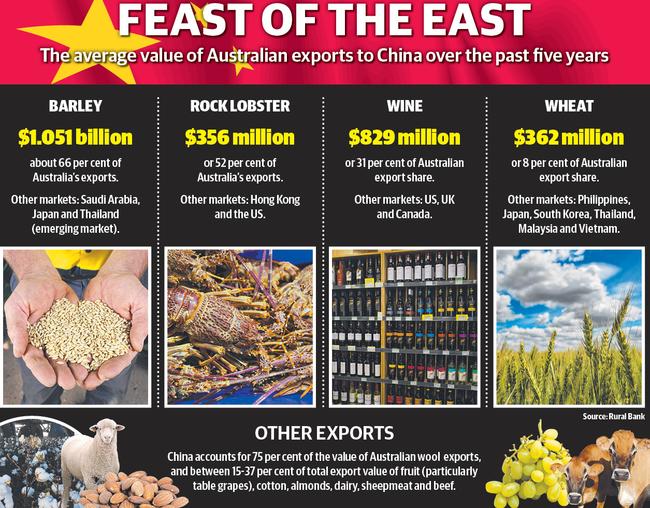

Agriculture is casting its eye to new markets amid fears of which sector could be next on China’s hit list. Here’s the state of play for our major exporters.

AUSTRALIA’S agricultural exporters are scrambling to find new markets and preparing their ‘plan B’, amid fears China’s attack on the $14 billion trade will continue.

Wine exporters are bracing for interim tariffs as soon as next week, Aussie wool growers are anxiously watching for any sign of disruption in their biggest market – and some horticulture producers are already anticipating not sending any product to Chinese ports this season.

It follows what some experts have described as an “unprecedented escalation” from Beijing in its tactics, with rumours last week China would ban Australian imports worth up to $6 billion from seven sectors, including wine, lobster, sugar, barley and timber.

While the Federal Government has said evidence of any blanket bans has yet to be seen, the Department of Agriculture has warned exporters to “fully consider their own risk and potential losses” and “seek advice from importers” before sending goods.

In a bitter twist, the latest developments comes mere weeks ahead of the China-Australia free-trade agreement reaching its five-year milestone.

Former trade minister Andrew Robb – who negotiated the much-lauded final deal – urged Australian agriculture to maintain its “trust and mutual respect” with China’s commercial sector.

“It’s been my observation that the trading relationship has never been stronger – but the political relationship, I don’t think it’s quite turned to custard, but it’s not in good shape,” Mr Robb said.

“We’ve hit a few potholes on the political side, now we’ve got to focus on fixing those potholes … it all gets down to communication.”

Souring diplomatic tensions – on issues from Australia calling for an inquiry into the origins of COVID-19, to new foreign interference laws – have translated to strategic hits on the nation’s agriculture sector this year: 80 per cent tariffs on barley, five suspended beef abattoirs, a rumoured edict not to buy Aussie cotton, rock lobsters left rotting on a Shanghai airport tarmac, and an anti-dumping investigation into Australian wine.

Wine exporters are preparing for China to slap an interim tariff on imports while the investigation is underway; it has until next Monday to do so.

Taylors Wines managing director Mitchell Taylor said a Chinese tariff on Australian bottled wine of more than 100 per cent would derail the industry, which has grown exponentially off the back of surging demand from Chinese consumers for high-end Australian wine.

Mr Taylor, who sits on the board of Wine Australia, said it was unlikely a high tariff could be justified given the high cost of Australian wine in China. But the industry was already priming to look for alternative markets.

“We’re thinking North America, Canada and the UK to pivot, and we have to work with the federal government to build a better free-trade agreement in countries like India,” he said.

The sector with arguably the greatest reliance on Chinese buying power is wool, which sells up to 92 per cent of its product to China each week, with greasy wool worth $1.9 billion annually.

National Council of Wool Brokers of Australia president Rowan Woods said demand from Chinese buyers had been “sporadic” in recent weeks, but prices were gradually climbing.

Australia produces 90 per cent of the world’s fine apparel wool, needed at China’s textile mills, but Mr Woods warned against complacency.

“We have not seen any evidence (of bans) at the coalface, but we are aware of (concerns) and watchful, and growers are nervous,” he said.

“(Other markets) such as Italy and India are subdued due to COVID. Make no bones about it, if the China trade stopped for some reason our market would be very, very sad.”

Diplomatic developments with China have also struck fear into many horticultural producers who have become heavily reliant on their Chinese exports, now accounting for about $1 billion.

Fruit and vegetable growers can’t quickly find alternative markets due to the produce’s perishability and the lack of market access protocols with other nations, which can take years to negotiate.

One table grape grower, who wanted to remain anonymous, was already planning the season ahead on the basis of not being able to export to China.

“Anyone who has been looking at what’s been going on between China, the US and Australia has been trying to prepare but no one can replace 40 per cent of their crop overnight,” he said.

“We have the FTA with China and are all geared up to supply this market. Farms have doubled in size, there’s no such thing as a small grower anymore and it’s all off the back of China.”

Mattina Fresh development manager Tom Panna said Australian producers had not focused enough on other markets because “everyone has been caught up with China”.

“Now everyone is sitting back and saying, ‘what should we do?’,” Mr Panna said.

He anticipated profitability will be shot for many growers this year, if they are forced to sell into the domestic market over China.

However, head of the Australia-China Relations Institute James Laurenceson said Beijing’s latest action, in suggesting a hit list of seven banned goods, was “quite unprecedented” and questioned if it was an outright ban.

“It’s one thing to make up a bogus, food safety reason to block a shipment of lobsters but in this case … if suddenly those goods can’t get in to China, any plausible deniability would vanish,” Prof Laurenceson said.

However, he said the mere rumour of a ban would make Chinese importers reluctant to order Australian goods, “and that in itself will have a negative impact”.

Mr Robb said calls for trade diversification right now were difficult due to countries dealing with the fallout from COVID-19.

“Our exporters aren’t silly, they know diversification does mitigate risk but at the moment, you try to travel to India to open up new markets – it’s hard enough at any time, much less when a country’s wracked by COVID,” he said.

“(Maintaining) trust with the commercial sector in China is critically important for the near to midterm.”

THE WEEKLY TIMES EDITORIAL

The new ball game with China

ALMOST five years ago, Australian agriculture was heralding the launch of the China-Australia free-trade agreement.

Lauded as saving exporters $300 million each year and deepening ties with our major trading partner, industry was excited by the opportunities it held.

Yet here we are, five years later, anxiously watching Beijing’s next move, trying to guess who might be next on its hit list as the diplomatic relationship continues to sour.

Australian agricultural exporters generally enjoy good business relationships with China’s importers.

But can those strong ties withstand the worsening political relationship? Australia should not betray its values and bend to another nation’s will, but it is fair to ask: how much of a beating can one sector take?

What may seem minor collateral damage to the total trading picture — $2 million in rock lobsters here, $600 million in barley there — is major pain for Australian producers, who built their trade on the paths our government created and put trust in the new relationships made.

Evidence of a blanket ban on seven sectors, including wine, sugar and barley, has yet to materialise, and may not even come to pass.

But the suggestion alone is enough to shake market confidence. If they weren’t already, Australian exporters are definitely exploring new markets. No, we should not and cannot turn our backs on the good business ties already made with China; China will continue to be important, and finding new partners is going to take time and effort.

But it will be effort well expended: because what good is a partner who won’t play by the rules?